The First Amendment Guarantees ALL Freedoms, including a Truthful Press

Does a state have the right to secede from the union?

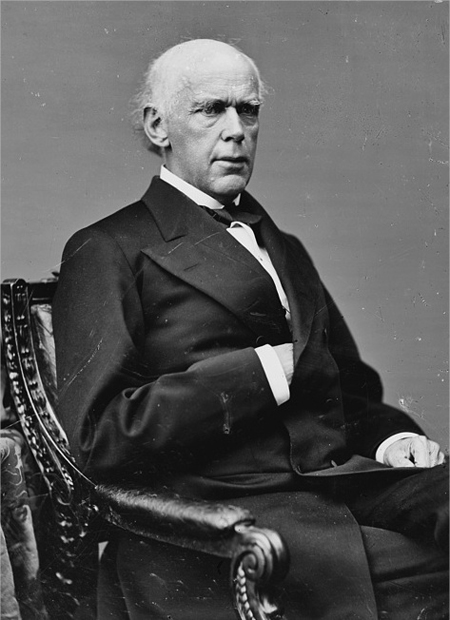

Chief Justice Chase wrote:

"The Union of the States never was a purely artificial and arbitrary relation. It began among the Colonies, and grew out of common origin, mutual sympathies, kindred principles, similar interests, and geographical relations. It was confirmed and strengthened by the necessities of war, and received definite form and character and sanction

Chief Justice Salmon Portland Chase

But the perpetuity and indissolubility of the Union by no means implies the loss of distinct and individual existence, or of the right of self-government, by the States. Under the Articles of Confederation, each State retained its sovereignty, freedom, and independence, and every power, jurisdiction, and right not expressly delegated to the United States. Under the Constitution, though the powers of the States were much restricted, still all powers not delegated to the United States nor prohibited to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people. And we have already had occasion to remark at this term that the people of each State compose a State, having its own government, and endowed with all the functions essential to separate and independent existence, and that, "without the States in union, there could be no such political body as the United States." Not only, therefore, can there be no loss of separate and independent autonomy to the States through their union under the Constitution, but it may be not unreasonably said that the preservation of the States, and the maintenance of their governments, are as much within the design and care of the Constitution as the preservation of the Union and the maintenance of the National government. The Constitution, in all its provisions, looks to an indestructible Union composed of indestructible States.

Therefore, when Texas became one of the United States, she entered into an indissoluble relation. All the obligations of perpetual union, and all the guaranties of republican government in the Union, attached at once to the State. The act which consummated her admission into the Union was something more than a compact; it was the incorporation of a new member into the political body. And it was final. The union between Texas and the other States was as complete, as perpetual, and as indissoluble as the union between the original States. There was no place for reconsideration or revocation, except through revolution or through consent of the States.

Considered therefore as transactions under the Constitution, the ordinance of secession, adopted by the convention and ratified by a majority of the citizens of Texas, and all the acts of her legislature intended to give effect to that ordinance, were absolutely null. They were utterly without operation in law. The obligations of the State, as a member of the Union, and of every citizen of the State, as a citizen of the United States, remained perfect and unimpaired. It certainly follows that the State did not cease to be a State, nor her citizens to be citizens of the Union. If this were otherwise, the State must have become foreign, and her citizens foreigners. The war must have ceased to be a war for the suppression of rebellion, and must have become a war for conquest and subjugation.

Our conclusion therefore is that Texas continued to be a State, and a State of the Union, notwithstanding the transactions to which we have referred. And this conclusion, in our judgment, is not in conflict with any act or declaration of any department of the National government, but entirely in accordance with the whole series of such acts and declarations since the first outbreak of the rebellion.

..... While Texas was controlled by a government hostile to the United States, and in affiliation with a hostile confederation, waging war upon the United States, senators chosen by her legislature, or representatives elected by her citizens, were entitled to seats in Congress, or that any suit instituted in her name could be entertained in this court. All admit that, during this condition of civil war, the rights of the State as a member, and of her people as citizens of the Union, were suspended. The government and the citizens of the State, refusing to recognize their constitutional obligations, assumed the character of enemies, and incurred the consequences of rebellion.

There being then no government in Texas in constitutional relations with the Union, it became the duty of the United States to provide for the restoration of such a government. But the restoration of the government which existed before the rebellion, without a new election of officers, was obviously impossible, and before any such election could be properly held, it was necessary that the old constitution should receive such amendments as would conform its provisions to the new conditions created by emancipation, and afford adequate security to the people of the State...... The President of the United States issued a proclamation appointing a provisional governor for the State and providing for the assembling of a convention with a view to the reestablishment of a republican government under an amended constitution, and to the restoration of the State to her proper constitutional relations. A convention was accordingly assembled, the constitution amended, elections held, and a State government, acknowledging its obligations to the Union, established.

The power exercised by the President was derived from his constitutional functions, as commander-in-chief, and, so long as the war continued, it cannot be denied that he might institute temporary government within insurgent districts occupied by the National forces, or take measures in any State for the restoration of State government faithful to the Union, employing, however, in such efforts, only such means and agents as were authorized by constitutional laws.

But the power to carry into effect the Guaranty Clause is primarily a legislative power, and resides in Congress. 'Under the fourth article of the Constitution, it rests with Congress to decide what government is the established one in a State. For, as the United States guarantee to each State a republican government, Congress must necessarily decide what government is established in the State before it can determine whether it is republican or not.'

The action of the President must therefore be considered as provisional... The governments which had been established and had been in actual operation under executive direction were recognized by Congress as provisional, as existing, and as capable of continuance..... The necessary conclusion is that the suit was instituted and is prosecuted by competent authority.

.... Title of the State was not divested by the act of the insurgent government in entering into this contract."

Texas v. White, 74 U.S. 700 (1869).

[Note that Salmon Chase was appointed by Abraham Lincoln as a cabinet member and was a leading Union figure during the war against the South].

It is noteworthy that President Lincoln considered Texas, but no other state, to have "been a State out of the Union." [He argued that that the original 13 states "passed into the Union" even before 1776; united to declare their independence in 1776; declared a "perpetual" union in the Articles of Confederation two years later; and finally created "a more perfect Union" by ratifying the Constitution in 1788].

It is also noteworthy that two years after that decision, President Grant signed an act entitling Texas to U.S. Congressional representation, readmitting Texas to the Union.

Either the Supreme Court was wrong in claiming Texas never actually left the Union or the Executive (President Grant) was wrong in "readmitting" a state that, according to the Supreme Court, had never left. Both can't be logically or legally true.

To be clear: Within a two year period, two branches of the same government took action with regard to Texas on the basis of two mutually exclusive positions -- one, a judicially contrived "interpretation" of the US Constitution, argued essentially from silence, and the other a practical attempt to remedy the historical fact that Texas had indeed left the Union, the very evidence for which was that Texas had recently met the demands imposed by the same federal government as prerequisite conditions for readmission. If the Supreme Court was right, then the very notion of prerequisites for readmission would have been moot -- a state cannot logically be readmitted if it never left in the first place.

Chapters One, Two and Three are complete. To be continued in Future Chapters.

Diane Rufino has her own blog For Love of God and Country. Come and visit her. She'd love your company.

| Does a state have the right to secede from the union? | In the Past, Body & Soul | Does a state have the right to secede from the union? |