Publisher's Note: This post appears here courtesy of the John Locke Foundation. The author of this post is Jon Sanders.

When government decides to buy something, cost increases are sure to follow. One reason is that people are generally less cost-conscious when they're spending other people's money. Government decision-makers are people spending revenues collected from other people.

Another reason is that, when politics are involved in the government decision to buy - or

"invest" - in something, the thing being bought has not only a material function, but also a political function. The material function is worth a certain amount, yes, but the political function can be worth much, much more - to the politicians seeking the purchase.

Still, since other people's money is involved, cost overruns aren't deal-breakers the way they would be in the private sector. Nevertheless, there can be cost overruns big enough to cause even politicians making deals on other people's dimes to rethink a purchase. There are definite but also practical limits to other people's money, and there are other projects politicians desire. A pet project could be stopped if it grows so expensive as to crowd out other desired purchases or make people uncomfortably aware (with electoral risks) of the costs they're being made to bear.

So it is with government projects to build offshore wind facilities.

Politico on July 26, 2023, certainly captured the moment - costs of constructing offshore wind are growing out of control, and the biggest victim is the biggest politician - in a recent lede paragraph:

"A grim financial outlook for the country's offshore wind power industry is threatening President Joe Biden's most important energy plans."

Once readers get past the jeremiads about Democratic governors'

"climate plans" and promised

"union jobs," they learn about the problems wind project developers have if they can't get even more money from the federal or state governments, which ultimately mean from people in their capacities as taxpayers and ratepayers. They include:

Atlantic Shores says its costs have gone up 30 percent since the project was approved by the state in 2021. It faces the same rising costs that other offshore wind projects do. Inflation is up - the cost of steel has soared since the pandemic - interest rates are higher and the labor market is tighter. ... New Jersey's projects are not outliers.

Companies with contracts to supply Massachusetts are scrapping their plans, paying penalties to terminate agreements that are no longer profitable. Rhode Island's utility isn't moving forward with a potential second offshore wind project after costs were higher than expected. ...

In New York, Equinor and Orsted petitioned the state for bigger payments for their projects in June. The subsidies will ultimately be paid by ratepayers through their electricity bills once the projects begin producing energy.

Here are a few other recent headlines:

Reuters, August 1, 2023:

BP (BP.L) and its partner Equinor (EQNR.OL) are renegotiating the terms of power supply agreements linked to their giant wind developments off the U.S. East Coast, BP CEO Bernard Looney said on Tuesday.

In 2020, BP paid Equinor $1.1 billion for a 50% stake in the venture to develop the Empire and Beacon offshore wind projects with a total capacity of 3,300 megawatt.

"We will not develop projects that don't meet our returns thresholds" of 6% to 8%, Looney said.

OilPrice.com, August 2, 2023

A financial crisis is unfolding in the offshore wind power industry. The ultra-efficient and reliable form of clean energy production is an essential component of all of the world's possible decarbonization pathways, but soaring inflation costs have undercut the sector's growth and left major projects dead in the water just when their output is most needed. A major policy shift is in order, but the public and private sector are at loggerheads as to who should have to pay for the increasingly expensive development plans. ...

"The expense associated with a typical US offshore project, before bonus tax credits related to the Inflation Reduction Act, has increased by 57% since 2021," Bloomberg recently reported, citing figures from BloombergNEF. "Inflation in the cost of components and labor explain about 40% of that and the rest is tied to rising interest rates." This means that any developers who signed long-term development contracts before the sharp increase in costs must now either re-negotiate their deals or walk away from them entirely.

This month has seen a disastrous number of canceled and abandoned offshore wind deals which "erased billions of US dollars in planned spending" in the final week of July alone, according to Fortune. Spanish utility Iberdrola SA agreed to pay $48.9m in fines to cancel a wind power contract off the coast of Massachusetts. In Rhode Island, Danish developer Orsted A/S's bid to produce offshore wind power was rejected due to rising operational and development costs. And a plan for a wind farm off the shore of the United Kingdom has

also been culled by Swedish state-owned utility Vattenfall AB, who - you guessed it - blamed inflation. ...

"Offshore wind is an outlier though because, unlike onshore wind and solar power, it was still at the high end of the cost curve before this financial shock," reports Bloomberg. This means that investing in offshore wind must be the project of governments, rather than the private sector. In the long term, offshore wind is an essential investment for meeting climate goals, but in the short term it's an economic failure. [Emphasis added.]

I suppose we should acknowledge the almost cultlike repetition of the mantra that

"meeting climate goals" is impossible without unaffordable offshore wind capacity, ignoring the intermittency of wind-power and the inability to coordinate wind to consumer needs, and consequently ignoring zero-emissions nuclear, a baseload resource that is steady, reliable, and dispatchable.

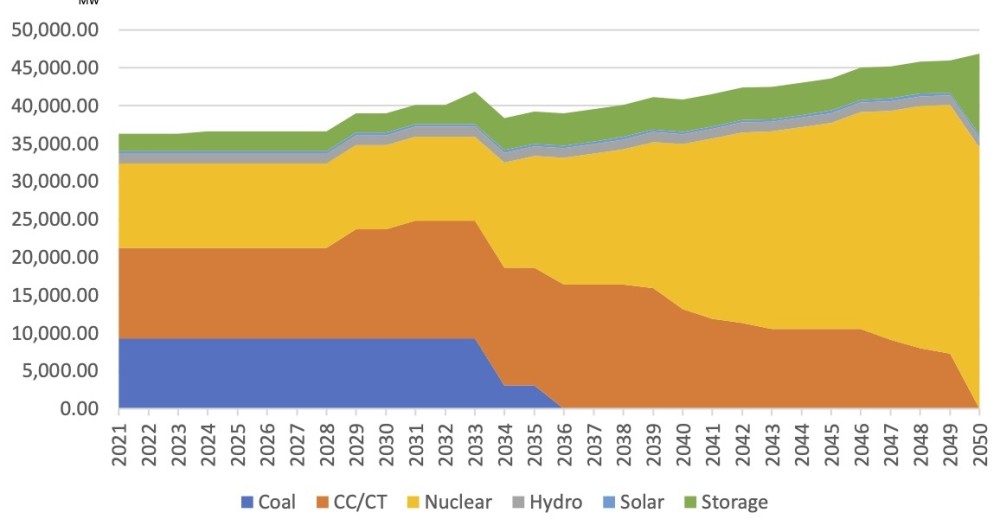

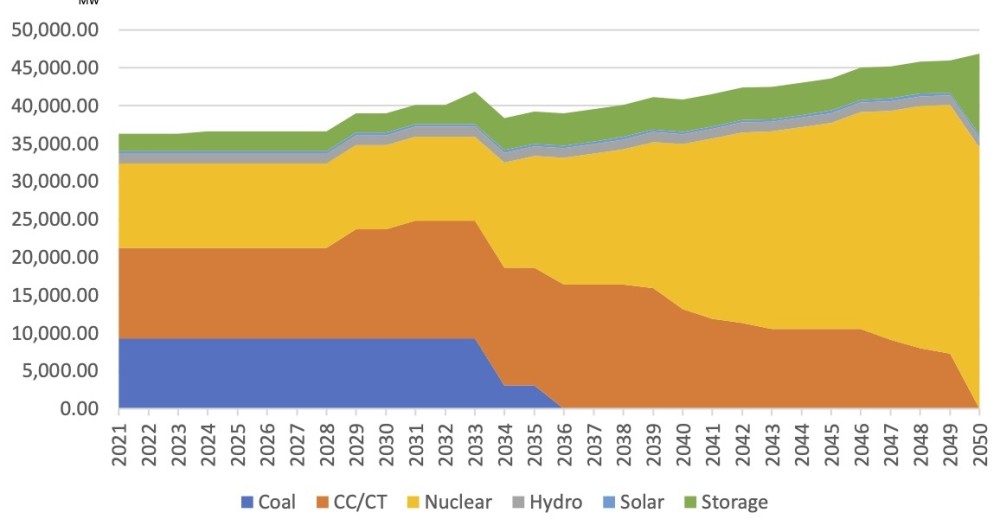

Locke's Center for Food, Power, and Life has demonstrated to the North Carolina Utilities Commission that, with new nuclear, we can achieve the political goal of reaching

"carbon neutrality" by 2050 without wind - and also, because state law requires maintaining grid reliability and charting the least-cost path, it is essential to get there with new nuclear, not offshore wind.

Model Least Cost Decarbonization Portfolio: Total Installed Capacity by Year

Barron's, July 21, 2023

Financially, the industry is teetering, with a parade of companies planning to renegotiate or pull out of contracts, jeopardizing plans for projects that were expected to provide electricity for millions of homes. Inflation is erasing profits, causing some of the largest energy firms in the world to back away. "Returns on offshore wind are becoming more and more challenged," Shell CEO Wael Sawan told Barron's last month, just days after a Shell joint venture said it would pull out of a power contract in Massachusetts. Shell won't build renewable projects that can't earn initial returns of 6% to 8%, he said.

At least eight multinational companies in three states have quietly started to back out of wind contracts, or ask to renegotiate deals in ways that will pass more costs to consumers. Beyond Shell (ticker: SHEL), they include BP (BP), Denmark's Orsted (DNNGY), Norway's Equinor (EQNR), Spain's Iberdrola (IBDRY), Portugal's Energias de Portugal (EDPFY), and France's Engie (ENGIY) and state-owned Electricite de France. The projects those companies are building will collectively cost tens of billions of dollars to construct and connect to the grid. The cost problems they're facing make offshore wind a dicey investment proposition today, with the potential for substantial write-downs ahead. ...

For years, the cost of installing the turbines was too high compared with the power that those turbines produced. Europeans have been less sensitive to higher prices because they already pay a premium for electricity compared with American consumers, who benefit from abundant coal and natural-gas reserves.

A decade ago, the U.S. government estimated the cost of electricity from a new offshore wind farm at more than $200 per megawatt-hour, twice as expensive as coal, and three times more than advanced natural-gas-fired plants. Since then, offshore wind costs have fallen dramatically-more than half, by most measures. The U.S. is also giving tax credits to qualifying projects that can be worth as much as $26 per megawatt-hour, bringing offshore wind costs to around $75-about $15 cheaper than a new coal plant. ...

As competition rose, bids on acreage in one section of the ocean off New York skyrocketed last year. Several European companies, including joint ventures involving TotalEnergies (TTE) and Shell, paid more than $700 million each for sections of the ocean bottom. The parcels contained less acreage than farms other companies had leased for less than $10 million prior to the pandemic, according to Freshney, the Credit Suisse analyst. "The cost just went through the roof," he says. "It was a bubble."