Committed to the First Amendment and OUR Freedom of Speech since 2008

The Constitution: Is it Still as Relevant Today as it was Years Ago?

Publisher's Note: This 3rd installment in Diane Rufino's series examining Our Founding Principles delves into the intricate development and design of the United States Constitution. All politicians are sworn to defend this hallowed document, so ask yourself while reading Diane's treatise: How much does your representative know, or even care about this blueprint to our nation's past and our future.

"The Constitution is not an instrument for the government to restrain the people; It is an instrument for the people to restrain the government - lest it comes to dominate our lives and interests." -- Patrick Henry

The Constitution is the keystone of our nation. It is the great guarantor of liberty. That original document, with the Bill of Rights, constitutes the charter of our freedom. Just as they did over 220 years ago, the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution are what makes us a free people today. Keeping these documents alive, and understanding and protecting them, depends on all of us: If people don't understand and value their rights, if they don't understand where their rights come from and how they are protected, how will they know when the government tries to take them away?

The Constitutional Convention: The Drafting of the Constittution

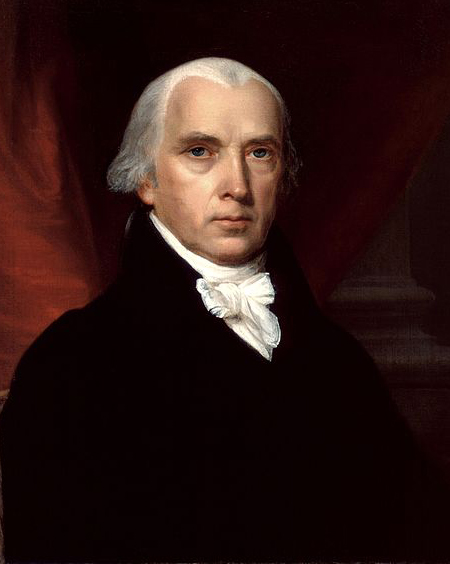

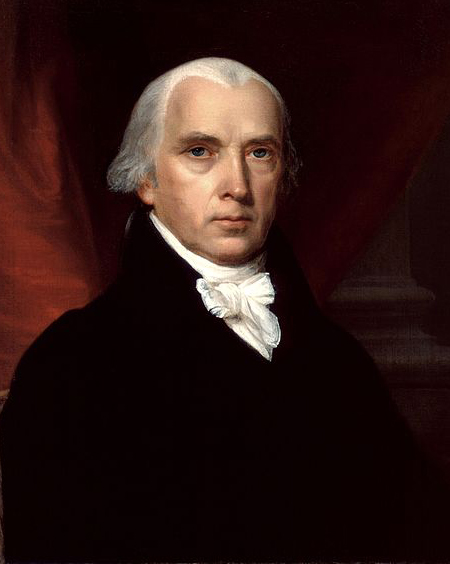

The Constitutional Convention (also known as the Philadelphia Convention) took place from May 25 to September 17, 1787, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Its purpose was to address problems in governing the United States of America under the Articles of Confederation following independence from Great Britain. The Convention was originally intended to amend the Articles of Confederation to make it more effective in dealing with issues common to all the states and acting on their behalf. Apparently, the intention of certain delegates, namely James Madison and Alexander Hamilton, was not to amend the Articles but rather to create a new government altogether. The delegates persuaded a very sick and debilitated George Washington to act as the President of the convention and to preside over it after several attempts to organize such a meeting had failed to spark sufficient interest.

dealing with issues common to all the states and acting on their behalf. Apparently, the intention of certain delegates, namely James Madison and Alexander Hamilton, was not to amend the Articles but rather to create a new government altogether. The delegates persuaded a very sick and debilitated George Washington to act as the President of the convention and to preside over it after several attempts to organize such a meeting had failed to spark sufficient interest.

The 55 delegates who drafted the Constitution included many men who we consider today as our "Founding Fathers." These are the men we credit for giving us our new nation, as so perfectly conceived and designed. A few of our most important Founders were not present at the Convention. Thomas Jefferson, one of our most prolific and well-read Founders, was in France during the Convention, acting as Minister to that country. John Adams was also abroad on official duty for the newly-independent nation, as Minister to Great Britain. Patrick Henry was also absent; he refused to go because he "smelt a rat in Philadelphia, tending toward the monarchy." He might have been referring to Alexander Hamilton, who strongly admired the British monarchy. Also absent were John Hancock and Samuel Adams. All the states sent delegates to the Convention, except Rhode Island which refused to send any.

Connecticut:

Oliver Ellsworth*

William Samuel Johnson

Roger Sherman

Delaware:

Richard Bassett

Gunning Bedford, Jr.

Jacob Broom

John Dickinson

George Read

Georgia:

Abraham Baldwin

William Few

William Houstoun*

William Pierce*

Maryland:

Daniel Carroll

Luther Martin*

James McHenry

John Francis Mercer*

Daniel of St. Thomas Jenifer

Massachusetts:

Elbridge Gerry*

Nathaniel Gorham

Rufus King

Caleb Strong*

New Hampshire:

Nicholas Gilman

John Langdon

New Jersey:

David Brearley

Jonathan Dayton

William Houston*

William Livingston

William Paterson

New York:

Alexander Hamilton

John Lansing, Jr.*

Robert Yates*

North Carolina:

William Blount

William Richardson Davie*

Alexander Martin*

Richard Dobbs Spaight

Hugh Williamson

Pennsylvania:

George Clymer

Thomas Fitzsimons

Benjamin Franklin

Jared Ingersoll

Thomas Mifflin

Gouverneur Morris

Robert Morris

James Wilson

South Carolina:

Pierce Butler

Charles Cotesworth Pinckney

Charles Pinckney

John Rutledge

Virginia:

John Blair

James Madison

George Mason*

James McClurg*

Edmund Randolph*

George Washington

George Wythe*

If we look back on our grade school education, we remember being taught the very fundamentals of what went on at the Constitutional Convention. We remember the key areas of contention between the individual states - how the government should be structured, how the representatives from the states should be apportioned, how the interests of the smaller states and the interests of the larger states can both be equally represented in government, how the states can retain their sovereign power in the face of a centralized, federal government, and what to do about the slaves and the issue of slavery. But so much more was accomplished. The Constitutional Convention and the drafting of the Constitution represented something much more monumental and significant.

First, let's review the general areas of contention between the states.

Almost immediately, it was understood that our nation would need to be a republic rather than a true democracy. Most people assume that this country is a democracy, but it isn't truly so. It is a republic, or a democratic republic as some call it. Understanding the difference between these two "forms" of government is essential to appreciating the fundamentals involved. A "democracy" operates by the direct majority vote of the people. When an issue is to be decided, the entire population votes on it and the majority wins and rules the day. The Founders explained that democracy rule is one that is guided by the majority "feeling." (ie, how the majority happens to be "feeling" at the time).

The Founders therefore termed it "mobocracy." Example: in a democracy, if a majority of the people decides that the minority group can no longer own property, then the minority group is no longer allowed to own property. In a Democracy, the individual, and any group of individuals composing any minority group, have no protection against the unlimited power of the majority. As James Madison wrote: "Theoretic politicians, who have patronized this species of government, have erroneously supposed, that by reducing mankind to a perfect equality in their political rights, they would, at the same time, be perfectly equalized and assimilated in their possessions, their opinions, and their passions."

A "republic" on the other hand is where the general population elects representatives who then are constrained in their representation by the Constitution and other laws. A republic is a nation ruled by law. There is a degree of insulation between the people (who might try to rule in a frenzied mob style) and government rule. A republican form of government has a very different purpose and an entirely different form, or system, of government than a pure democracy. Its purpose is to control rule-making. More specifically, its purpose is to control the majority. It is designed to protect the minority from oppression by the majority. It is designed to protect the individual's (EVERY individual's) God-given, unalienable rights and the liberties of people in general. Our particular republican form of government has a separation of power because our Founders understood the inherent weakness and depravity of man. They knew that people are basically weak, sinful and corruptible, and will pit one men against another other, making it difficult to pass laws and make changes that are fair to everyone.

With regard to the choice of a republican form of government, Madison made an observation in The Federalist Papers (Federalist No. 55): "As there is a degree of depravity in mankind which requires a certain degree of circumspection and distrust: So there are other qualities in human nature, which justify a certain portion of esteem and confidence. Republican government (that of a Republic) presupposes the existence of these qualities in a higher degree than any other form. Were the pictures which have been drawn by the political jealousy of some among us, faithful likenesses of the human character, the inference would be that there is not sufficient virtue among men for self government; and that nothing less than the chains of despotism can restrain them from destroying and devouring one another." [See later for a discussion of "Democracy v. Republic" by David Barton of Wallbuilders.com]

It is worth noting that the first genuine and solidly-founded republic in all history was the one created by the Constitution of Massachusetts in 1780. The Founders didn't have to look far for a template for our US Constitution.

As a very old and very tired Benjamin Franklin was leaving the building where, after four months of hard work, the Constitution had been completed and signed, a lady asked him what kind of government the convention had created. The very wise Franklin replied; "A Republic, ma'am if you can keep it."

At the Convention, there were 3 parties, each with a strong opinion as to the purpose of a government representing all the states. The first group was the Monarchists who were intent on stripping the individual states of all their sovereign powers and substituting one unitary, all-powerful government, to be responsible for all land and all people. Its most vocal proponent was Alexander Hamilton. He made a famous speech at the Convention in which he avowed his admiration for the British constitution and expressed his desire that the delegates model the American government after the British system. He called for a president who would be appointed for life, senators with life terms, and power vested in the president to appoint all governors. Each of these mirrors the British model.

The second group was the Nationalists, who pushed for a strong centralized "national" government and was against sharing of power with the states. Its most vocal proponent was James Madison. It would have a national executive branch, a national legislative branch, and a national judiciary branch. There would be little or no deference or respect for the states. Specifically, Madison wanted a strong centralized (power centralized in the government) modeled after his state of Virginia and largely dominated by officials from Virginia. In fact, Madison arrived at the Convention several days early in order that he would have time to draft a series of proposals on which he believed the Constitution should be based. His intention was to introduce the other delegates to his proposals and then vote on them and ratify them. His series of proposals was known as the "Virginia Plan." Initially the delegates voted on the plan in approval but as the days and weeks went on, they overwhelmingly discarded it for the federalist system.

The third group was the Federalists, who luckily won the day at the Convention. They wanted the states to retain their sovereign power. Consequently, their system was one that divided the powers of government between the central government and state and local governments. This was obvious in the limited powers of the government, in the make-up of delegates in the legislative branch, including the election of Senators by the individual state legislatures rather than the people, the amendment process, and the jurisdiction assigned to the federal court system.

The issue on the mind of almost every representative at the Constitutional Convention was what kind of government was best for the new republic. Certain states submitted plans for a republican government, however, the most popular was the plan submitted by the Virginia delegation lead by James Madison (and including George Mason, Edmund Randolph, and even George Washington). The Virginia Plan, embracing a "nationalist" scheme, called for a government with three distinct branches: legislative, executive, and judicial. Using Montesquieu's theory of checks and balances it was intended to ensure that no group could have too much authority, which could lead to tyranny. Although the delegates supported most of the proposed principles of the Virginia Plan, they were in disagreement in certain areas of the plan. The highest debate concerned the section on representation in the legislative branch. The Virginia Plan proposed that representation in the legislatives houses would be based on population of the state. Small states objected saying that it would leave them helpless in a government dominated by larger states.

After the Virginia Plan was introduced, New Jersey delegate William Paterson asked for an adjournment to contemplate the Plan. Under the Articles of Confederation, each state had equal representation in Congress, exercising one vote each. The Virginia Plan threatened to limit the smaller states' power by making both houses of the legislature proportionate to population. On June 14-15, 1787, a small-state caucus met to create a response to the Virginia Plan. The result was the New Jersey Plan, to represent the interests of the small states.

Under the New Jersey Plan, the existing Continental Congress would remain (equal representation of states in Congress), but it would be granted new powers, such as the power to levy taxes and force their collection. An executive branch was created (multi-person executive), which would be elected by Congress. Executives would serve a single term and would be subject to recall on the request of state governors. The plan also created a judiciary that would serve for life, to be appointed by the executives. Lastly, any laws set by Congress would take precedence over state laws. When Paterson reported the plan to the convention on June 15, 1787, it was ultimately rejected, but through its proposal, the smaller states were at least able to make their issues and concerns known.

Alexander Hamilton proposed his own plan. It was known as the British Plan, because it so strongly resembled to the British system of a strong centralized government and a leader, called a "Governor," who would be elected by electors (chosen by the people) to serve a life-term. This "Governor" would have an absolute veto power over bills. In his plan, Hamilton advocated eliminating state sovereignty and consolidating the states into a single nation. The plan featured a bicameral (2-chamber) legislature, with the lower house elected by the people for three years and the upper house elected by electors who would serve for life. Not only would a national legislature appoint state governors, but it would have complete veto power over any state legislation.

Hamilton presented his plan to the Convention on June 18, 1787, but it was immediately rejected because it resembled the British system too closely. The states had just found a war for its independence from that system. More importantly, it was rejected because it abolished state sovereignty.

A compromise, known as the Connecticut Compromise (forged by Roger Sherman from Connecticut), was proposed on June 11 which would blend the Virginia (large-state) and New Jersey (small-state) plans and thus combine the important elements of both. Sherman suggested a two-house national legislature, but proposed "That the proportion of suffrage in the first branch [house] should be according to the respective numbers of free inhabitants; and that in the second branch or Senate, each State should have one vote and no more." The compromise was rejected at first, but on July 23, the representation in both houses was finally settled (with 2 Senators per state).

Another area which caused much deliberation was the issue of Slavery. It turned out to be the most controversial issue confronting the delegates. Slaves accounted for about one-fifth of the population in the American colonies. Most of them lived in the Southern colonies, where they made up 40% of the population.

There were three slavery-related issues which were very hotly debated at the Convention - (1) One was the question of whether slaves would be counted as part of the population in determining representation in Congress or merely considered property and not entitled to representation; (2) Another was the question of the slave trade and what to do with it; and (3) And the most important was whether slavery should be abolished altogether in the formation of a United States.

With respect to the first issue, a bitter debate resulted over whether or not blacks should be added equally with whites in the computation of the population Delegates from states with a large population of slaves wanted the slaves to be used to their benefit. As such, they wanted slaves to be considered persons in determining representation (to boost their representation in Congress) but as property for the purposes of apportionment of taxes in relation to the state's population (ie, for the purposes of the government levying taxes on the states on the basis of population). Delegates from states where slavery had disappeared or almost disappeared argued that slaves should be included in taxation, but not in determining representation. Finally, delegate James Wilson (from Pennsylvania) and Roger Sherman (from Connecticut), proposed the Three-Fifths Compromise, which was designed to meet the demands of both sides. Recognizing the desire of the South for power and influence in government and wanting to provide an incentive for those states to ratify the Constitution, the three-fifths compromise allowed the government to count slaves only as partial people - each slave would count as "three fifths of all other persons" (Article I, Section 2, addressing representation in Congress and apportionment of taxes). The Compromise was eventually adopted by the Convention.

Another issue at the Convention was what should be done about the slave trade. All states except two had already adopted provisions in their state constitutions to abolish slavery outright or to outlaw the importation of slaves or to phase it out. (North Carolina has already outlawed the importation of slaves). Georgia and South Carolina threatened to leave the Convention if the slave trade was banned outright. The delegates constantly worried that the Constitution they ultimately drafted would not be ratified by the individual states and so, in order that the southern states would not prevent the ratification, the issue of the slave trade was postponed. A compromise of sorts was worked out. Article I, Section 9, subpart 1 lists those "Powers which are Forbidden to the Congress" or rather "Limits on Congress" and subpart 1 was drafted to read: "There will be no prohibition of slavery before 1808." In other words, Congress would have no power to address the issue of the importation of slaves until the year 1808 (20 years from the signing of the Constitution).

The same concerns over the regulation of the slave trade applied to the discussion of abolishing slavery outright under the new Constitution. The delegates did not want to frustrate the adoption of a binding Constitution by alienating the southern states. Their support was desperately needed. The matter of slavery caused such a conflict between the northern states and the southern states that several southern states refused to join the Union if slavery was not permitted under the Constitution. Three states initially had a problem with abolishing slavery - Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina. And it wasn't that they didn't believe that slavery was morally wrong or that it should be abolished. They were more concerned about their local economies. These states struggled with the question of how they could achieve a smooth transition from an agricultural economy based on slavery to one that would not be dependent on slavery. They really wanted time to figure out how to gradually phase out slavery so that their economies would not suffer. North Carolina eventually admitted it was willing to discuss options and would be willing to agree to the abolition of slavery, but South Carolina and Georgia were not willing to give up their slaves at that time. Article I Section 9 subpart I reflects the discussions by the delegates, including those from the South, regarding the eventual transition from slavery.

George Mason of Virginia felt so strongly that it was an abomination for slavery to remain as the states set about to create their new nation, under the principles set out in the Declaration of Independence, that he said this: "This infernal traffic originated in the avarice of British merchants. They British government constantly checked the attempts of Virginia to put a stop to it. The present question concerns not the importing states alone but the whole Union. Maryland and Virginia have already prohibited the importation of slaves expressly. North Carolina had done the same in substance. Slavery discourages arts and manufacturing. The poor despise labor when they know there are slaves to do it. Every master of slaves is born a petty tyrant. They bring the judgment of Heaven on a country. As Nations cannot be rewarded or punished in the next world, they must in this. By an inevitable chain of causes and effects, Providence punishes national sins by national calamities."

Not all delegates were happy with the final product. 3 high profile delegates refused to sign it: George Mason (Virginia), Edmund Randolph (Virginia), and George Mason (Virginia), and Elbridge Gerry (Massachusetts).

The Constitution must not be looked at merely for what it says. The Constitution can only truly be appreciated for what it embraces. Our Founding Fathers, who were immensely well-read and intelligent men, recognized and embraced the most productive and fairest philosophies regarding freedom, representation, government, markets, and laws and sought to embody them in our Constitution. The particular drafting of the Constitution, therefore, addressed the need to embody each particular philosophy for our new nation. First and foremost, the Constitution was designed to put into practice the principles laid out in the Declaration of Independence. It was designed primarily to secure the individual's God-given, unalienable rights. After all, it was the Declaration of Independence which laid the principles which were to guide our independent nation and therefore represented our national values.

The Constitution was intended to be timeless. It was intended to withstand the test of time and establish a government that would survive eternal (that is, as long as its people remained moral and ethical and of course, beholden to the Constitution). One of the biggest debates today, especially because of the condition we find ourselves in as a nation, is whether the Constitution is indeed timeless or was it just the starting place for those to "mold" as they deemed necessary. The answer to that is to use common sense. As we have repeatedly deviated from the Constitution, we have progressed further and further away from the positive ideals and productive values that made our country great. The biggest argument that liberal-minded people today make is that the Constitution is out-of-date, out-of-touch with the American people, and ineffective to meet our growing diversity and our evolving society. They argue that the Founders are outdated and that they have lost relevance. They say all these things because they believe that our Founding Fathers were products of their era and could not foresee the societal change that has evolved in this country. Nothing could be farther from the truth. Our Founders absolutely understood how the society would develop. The men who gave us the greatest nation on Earth weren't just a couple of guys who went to the Constitutional Convention in 1787 to hammer out the wording of a Constitution that would be binding on all the states. These men were visionaries. These men did their homework. They were deeply devoted to creating a nation that would stand the test of time. They wanted to come up with a foundation, a Constitution, that would not wither with the times. And so for that purpose, they studied all the failed regimes of history and they looked at all the constitutions and founding documents of other nations and studied the reasons why they were unable to last long. So, there is nothing that we've seen in our developing history that other nations haven't dealt with and nothing that our Founders weren't able to foresee. As Machiavelli wrote: "Whoever wishes to foresee the future must consult the past; for human events ever resemble those of preceding times. This arises from the fact that they are produced by men who ever have been, and ever shall be, animated by the same passions, and thus they necessarily have the same results."

The problem with ignoring history is that each time history repeats itself, the price goes up. The stakes are higher. From their studies of history's failed regimes, they came up with core principles that are absolutely vital to prevent this country from going down those same paths. They were wise enough to predict and to warn us of what would happen should we fail to honor and respect those principles. And there is nothing we see here today in this country that the Founders have not written about or warned us about. All we need to do is take the time and make the effort to read the legacy of documents they have left us. The principles and concepts that the Founders gave us are the perfect template for a successful government and a successful and honorable nation are timeless.

In order to understand our Constitution and other founding documents, we Americans need to understand what issues concerned the individual states at the time of our founding. We need to understand the issues on the minds of the Framers in crafting our new nation and where they looked for guidance and vision and solutions. The states were concerned with their sovereign power and their reluctance to give any of it up. Most states also were concerned with their right to embrace their religious heritage. All states except for three wanted to make sure that our new nation, which proclaimed that "All Men are Created Equal" would be rid of the injustice that was slavery. In drafting a document that would bind all the states into a unified nation (a union of states), and do so harmoniously and to meet their legitimate expectations, the Founding Fathers had to address the following fundamental questions: How to divide the power up as between the States and the Government? How much power should the government have? How much will it need in order to be effective? What is the legal basis of our fundamental rights? Do our rights come from God or from the government? What is the proper foundation to protect human rights? How to make sure that fundamental freedom is not burdened by the government? How should the government be structured? How can power remain with the people and be checked from abuses? What is the proper system to represent the voice of the people? How should the individual states be represented in the government? Each of these issues is critical in understanding how our nation was created. Our national heritage stems from the decisions these men made in 1787 with respect to these issues.

The goal of the Founders at the Convention of 1787 was to reach a consensus or general agreement on concepts and principles that the Constitution should embrace rather than compromise. They wanted to reach a consensus on what the Constitution should provide rather than compromise. So before they went into a voting session, they made sure that they thoroughly discussed and debated each issue. After almost 4 months of such debate, they were able to reach a general consensus on just about everything - except the issues of slavery, proportionate representation, and regulation of commerce. These three issues eventually needed to be resolved by compromise.

The Founders honored their goal and resolved most issues by consensus rather than compromise. As "compromise" often reflects a tone of defeat and submission (it's been called a "lose-lose scenario since both sides lose something they hold as important), the strength of the Constitution is that its provisions eventually and predominantly arose out of consensus. The Constitution was the product of extreme patience on the part of our Founders as each used reason and logic to bring the minds of the delegates into agreement. They wanted to make sure that the absolute soundest principles and concepts were adopted for the type of free and fair nation they had envisioned. Not one of the Founding Fathers could have come up with the perfect Constitutional formula to create a stable nation representative of the people and protective of their rights by himself, and the delegates who attended the Constitutional Convention in 1787 knew this.

Go Back

"The Constitution is not an instrument for the government to restrain the people; It is an instrument for the people to restrain the government - lest it comes to dominate our lives and interests." -- Patrick Henry

The Constitution is the keystone of our nation. It is the great guarantor of liberty. That original document, with the Bill of Rights, constitutes the charter of our freedom. Just as they did over 220 years ago, the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution are what makes us a free people today. Keeping these documents alive, and understanding and protecting them, depends on all of us: If people don't understand and value their rights, if they don't understand where their rights come from and how they are protected, how will they know when the government tries to take them away?

The Constitutional Convention: The Drafting of the Constittution

The Constitutional Convention (also known as the Philadelphia Convention) took place from May 25 to September 17, 1787, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Its purpose was to address problems in governing the United States of America under the Articles of Confederation following independence from Great Britain. The Convention was originally intended to amend the Articles of Confederation to make it more effective in

dealing with issues common to all the states and acting on their behalf. Apparently, the intention of certain delegates, namely James Madison and Alexander Hamilton, was not to amend the Articles but rather to create a new government altogether. The delegates persuaded a very sick and debilitated George Washington to act as the President of the convention and to preside over it after several attempts to organize such a meeting had failed to spark sufficient interest.

dealing with issues common to all the states and acting on their behalf. Apparently, the intention of certain delegates, namely James Madison and Alexander Hamilton, was not to amend the Articles but rather to create a new government altogether. The delegates persuaded a very sick and debilitated George Washington to act as the President of the convention and to preside over it after several attempts to organize such a meeting had failed to spark sufficient interest.

The 55 delegates who drafted the Constitution included many men who we consider today as our "Founding Fathers." These are the men we credit for giving us our new nation, as so perfectly conceived and designed. A few of our most important Founders were not present at the Convention. Thomas Jefferson, one of our most prolific and well-read Founders, was in France during the Convention, acting as Minister to that country. John Adams was also abroad on official duty for the newly-independent nation, as Minister to Great Britain. Patrick Henry was also absent; he refused to go because he "smelt a rat in Philadelphia, tending toward the monarchy." He might have been referring to Alexander Hamilton, who strongly admired the British monarchy. Also absent were John Hancock and Samuel Adams. All the states sent delegates to the Convention, except Rhode Island which refused to send any.

Connecticut:

Oliver Ellsworth*

William Samuel Johnson

Roger Sherman

Delaware:

Richard Bassett

Gunning Bedford, Jr.

Jacob Broom

John Dickinson

George Read

Georgia:

Abraham Baldwin

William Few

William Houstoun*

William Pierce*

Maryland:

Daniel Carroll

Luther Martin*

James McHenry

John Francis Mercer*

Daniel of St. Thomas Jenifer

Massachusetts:

Elbridge Gerry*

Nathaniel Gorham

Rufus King

Caleb Strong*

New Hampshire:

Nicholas Gilman

John Langdon

New Jersey:

David Brearley

Jonathan Dayton

William Houston*

William Livingston

William Paterson

New York:

Alexander Hamilton

John Lansing, Jr.*

Robert Yates*

North Carolina:

William Blount

William Richardson Davie*

Alexander Martin*

Richard Dobbs Spaight

Hugh Williamson

Pennsylvania:

George Clymer

Thomas Fitzsimons

Benjamin Franklin

Jared Ingersoll

Thomas Mifflin

Gouverneur Morris

Robert Morris

James Wilson

South Carolina:

Pierce Butler

Charles Cotesworth Pinckney

Charles Pinckney

John Rutledge

Virginia:

John Blair

James Madison

George Mason*

James McClurg*

Edmund Randolph*

George Washington

George Wythe*

If we look back on our grade school education, we remember being taught the very fundamentals of what went on at the Constitutional Convention. We remember the key areas of contention between the individual states - how the government should be structured, how the representatives from the states should be apportioned, how the interests of the smaller states and the interests of the larger states can both be equally represented in government, how the states can retain their sovereign power in the face of a centralized, federal government, and what to do about the slaves and the issue of slavery. But so much more was accomplished. The Constitutional Convention and the drafting of the Constitution represented something much more monumental and significant.

First, let's review the general areas of contention between the states.

Almost immediately, it was understood that our nation would need to be a republic rather than a true democracy. Most people assume that this country is a democracy, but it isn't truly so. It is a republic, or a democratic republic as some call it. Understanding the difference between these two "forms" of government is essential to appreciating the fundamentals involved. A "democracy" operates by the direct majority vote of the people. When an issue is to be decided, the entire population votes on it and the majority wins and rules the day. The Founders explained that democracy rule is one that is guided by the majority "feeling." (ie, how the majority happens to be "feeling" at the time).

The Founders therefore termed it "mobocracy." Example: in a democracy, if a majority of the people decides that the minority group can no longer own property, then the minority group is no longer allowed to own property. In a Democracy, the individual, and any group of individuals composing any minority group, have no protection against the unlimited power of the majority. As James Madison wrote: "Theoretic politicians, who have patronized this species of government, have erroneously supposed, that by reducing mankind to a perfect equality in their political rights, they would, at the same time, be perfectly equalized and assimilated in their possessions, their opinions, and their passions."

A "republic" on the other hand is where the general population elects representatives who then are constrained in their representation by the Constitution and other laws. A republic is a nation ruled by law. There is a degree of insulation between the people (who might try to rule in a frenzied mob style) and government rule. A republican form of government has a very different purpose and an entirely different form, or system, of government than a pure democracy. Its purpose is to control rule-making. More specifically, its purpose is to control the majority. It is designed to protect the minority from oppression by the majority. It is designed to protect the individual's (EVERY individual's) God-given, unalienable rights and the liberties of people in general. Our particular republican form of government has a separation of power because our Founders understood the inherent weakness and depravity of man. They knew that people are basically weak, sinful and corruptible, and will pit one men against another other, making it difficult to pass laws and make changes that are fair to everyone.

With regard to the choice of a republican form of government, Madison made an observation in The Federalist Papers (Federalist No. 55): "As there is a degree of depravity in mankind which requires a certain degree of circumspection and distrust: So there are other qualities in human nature, which justify a certain portion of esteem and confidence. Republican government (that of a Republic) presupposes the existence of these qualities in a higher degree than any other form. Were the pictures which have been drawn by the political jealousy of some among us, faithful likenesses of the human character, the inference would be that there is not sufficient virtue among men for self government; and that nothing less than the chains of despotism can restrain them from destroying and devouring one another." [See later for a discussion of "Democracy v. Republic" by David Barton of Wallbuilders.com]

It is worth noting that the first genuine and solidly-founded republic in all history was the one created by the Constitution of Massachusetts in 1780. The Founders didn't have to look far for a template for our US Constitution.

As a very old and very tired Benjamin Franklin was leaving the building where, after four months of hard work, the Constitution had been completed and signed, a lady asked him what kind of government the convention had created. The very wise Franklin replied; "A Republic, ma'am if you can keep it."

At the Convention, there were 3 parties, each with a strong opinion as to the purpose of a government representing all the states. The first group was the Monarchists who were intent on stripping the individual states of all their sovereign powers and substituting one unitary, all-powerful government, to be responsible for all land and all people. Its most vocal proponent was Alexander Hamilton. He made a famous speech at the Convention in which he avowed his admiration for the British constitution and expressed his desire that the delegates model the American government after the British system. He called for a president who would be appointed for life, senators with life terms, and power vested in the president to appoint all governors. Each of these mirrors the British model.

The second group was the Nationalists, who pushed for a strong centralized "national" government and was against sharing of power with the states. Its most vocal proponent was James Madison. It would have a national executive branch, a national legislative branch, and a national judiciary branch. There would be little or no deference or respect for the states. Specifically, Madison wanted a strong centralized (power centralized in the government) modeled after his state of Virginia and largely dominated by officials from Virginia. In fact, Madison arrived at the Convention several days early in order that he would have time to draft a series of proposals on which he believed the Constitution should be based. His intention was to introduce the other delegates to his proposals and then vote on them and ratify them. His series of proposals was known as the "Virginia Plan." Initially the delegates voted on the plan in approval but as the days and weeks went on, they overwhelmingly discarded it for the federalist system.

The third group was the Federalists, who luckily won the day at the Convention. They wanted the states to retain their sovereign power. Consequently, their system was one that divided the powers of government between the central government and state and local governments. This was obvious in the limited powers of the government, in the make-up of delegates in the legislative branch, including the election of Senators by the individual state legislatures rather than the people, the amendment process, and the jurisdiction assigned to the federal court system.

The issue on the mind of almost every representative at the Constitutional Convention was what kind of government was best for the new republic. Certain states submitted plans for a republican government, however, the most popular was the plan submitted by the Virginia delegation lead by James Madison (and including George Mason, Edmund Randolph, and even George Washington). The Virginia Plan, embracing a "nationalist" scheme, called for a government with three distinct branches: legislative, executive, and judicial. Using Montesquieu's theory of checks and balances it was intended to ensure that no group could have too much authority, which could lead to tyranny. Although the delegates supported most of the proposed principles of the Virginia Plan, they were in disagreement in certain areas of the plan. The highest debate concerned the section on representation in the legislative branch. The Virginia Plan proposed that representation in the legislatives houses would be based on population of the state. Small states objected saying that it would leave them helpless in a government dominated by larger states.

After the Virginia Plan was introduced, New Jersey delegate William Paterson asked for an adjournment to contemplate the Plan. Under the Articles of Confederation, each state had equal representation in Congress, exercising one vote each. The Virginia Plan threatened to limit the smaller states' power by making both houses of the legislature proportionate to population. On June 14-15, 1787, a small-state caucus met to create a response to the Virginia Plan. The result was the New Jersey Plan, to represent the interests of the small states.

Under the New Jersey Plan, the existing Continental Congress would remain (equal representation of states in Congress), but it would be granted new powers, such as the power to levy taxes and force their collection. An executive branch was created (multi-person executive), which would be elected by Congress. Executives would serve a single term and would be subject to recall on the request of state governors. The plan also created a judiciary that would serve for life, to be appointed by the executives. Lastly, any laws set by Congress would take precedence over state laws. When Paterson reported the plan to the convention on June 15, 1787, it was ultimately rejected, but through its proposal, the smaller states were at least able to make their issues and concerns known.

Alexander Hamilton proposed his own plan. It was known as the British Plan, because it so strongly resembled to the British system of a strong centralized government and a leader, called a "Governor," who would be elected by electors (chosen by the people) to serve a life-term. This "Governor" would have an absolute veto power over bills. In his plan, Hamilton advocated eliminating state sovereignty and consolidating the states into a single nation. The plan featured a bicameral (2-chamber) legislature, with the lower house elected by the people for three years and the upper house elected by electors who would serve for life. Not only would a national legislature appoint state governors, but it would have complete veto power over any state legislation.

Hamilton presented his plan to the Convention on June 18, 1787, but it was immediately rejected because it resembled the British system too closely. The states had just found a war for its independence from that system. More importantly, it was rejected because it abolished state sovereignty.

A compromise, known as the Connecticut Compromise (forged by Roger Sherman from Connecticut), was proposed on June 11 which would blend the Virginia (large-state) and New Jersey (small-state) plans and thus combine the important elements of both. Sherman suggested a two-house national legislature, but proposed "That the proportion of suffrage in the first branch [house] should be according to the respective numbers of free inhabitants; and that in the second branch or Senate, each State should have one vote and no more." The compromise was rejected at first, but on July 23, the representation in both houses was finally settled (with 2 Senators per state).

Another area which caused much deliberation was the issue of Slavery. It turned out to be the most controversial issue confronting the delegates. Slaves accounted for about one-fifth of the population in the American colonies. Most of them lived in the Southern colonies, where they made up 40% of the population.

There were three slavery-related issues which were very hotly debated at the Convention - (1) One was the question of whether slaves would be counted as part of the population in determining representation in Congress or merely considered property and not entitled to representation; (2) Another was the question of the slave trade and what to do with it; and (3) And the most important was whether slavery should be abolished altogether in the formation of a United States.

With respect to the first issue, a bitter debate resulted over whether or not blacks should be added equally with whites in the computation of the population Delegates from states with a large population of slaves wanted the slaves to be used to their benefit. As such, they wanted slaves to be considered persons in determining representation (to boost their representation in Congress) but as property for the purposes of apportionment of taxes in relation to the state's population (ie, for the purposes of the government levying taxes on the states on the basis of population). Delegates from states where slavery had disappeared or almost disappeared argued that slaves should be included in taxation, but not in determining representation. Finally, delegate James Wilson (from Pennsylvania) and Roger Sherman (from Connecticut), proposed the Three-Fifths Compromise, which was designed to meet the demands of both sides. Recognizing the desire of the South for power and influence in government and wanting to provide an incentive for those states to ratify the Constitution, the three-fifths compromise allowed the government to count slaves only as partial people - each slave would count as "three fifths of all other persons" (Article I, Section 2, addressing representation in Congress and apportionment of taxes). The Compromise was eventually adopted by the Convention.

Another issue at the Convention was what should be done about the slave trade. All states except two had already adopted provisions in their state constitutions to abolish slavery outright or to outlaw the importation of slaves or to phase it out. (North Carolina has already outlawed the importation of slaves). Georgia and South Carolina threatened to leave the Convention if the slave trade was banned outright. The delegates constantly worried that the Constitution they ultimately drafted would not be ratified by the individual states and so, in order that the southern states would not prevent the ratification, the issue of the slave trade was postponed. A compromise of sorts was worked out. Article I, Section 9, subpart 1 lists those "Powers which are Forbidden to the Congress" or rather "Limits on Congress" and subpart 1 was drafted to read: "There will be no prohibition of slavery before 1808." In other words, Congress would have no power to address the issue of the importation of slaves until the year 1808 (20 years from the signing of the Constitution).

The same concerns over the regulation of the slave trade applied to the discussion of abolishing slavery outright under the new Constitution. The delegates did not want to frustrate the adoption of a binding Constitution by alienating the southern states. Their support was desperately needed. The matter of slavery caused such a conflict between the northern states and the southern states that several southern states refused to join the Union if slavery was not permitted under the Constitution. Three states initially had a problem with abolishing slavery - Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina. And it wasn't that they didn't believe that slavery was morally wrong or that it should be abolished. They were more concerned about their local economies. These states struggled with the question of how they could achieve a smooth transition from an agricultural economy based on slavery to one that would not be dependent on slavery. They really wanted time to figure out how to gradually phase out slavery so that their economies would not suffer. North Carolina eventually admitted it was willing to discuss options and would be willing to agree to the abolition of slavery, but South Carolina and Georgia were not willing to give up their slaves at that time. Article I Section 9 subpart I reflects the discussions by the delegates, including those from the South, regarding the eventual transition from slavery.

George Mason of Virginia felt so strongly that it was an abomination for slavery to remain as the states set about to create their new nation, under the principles set out in the Declaration of Independence, that he said this: "This infernal traffic originated in the avarice of British merchants. They British government constantly checked the attempts of Virginia to put a stop to it. The present question concerns not the importing states alone but the whole Union. Maryland and Virginia have already prohibited the importation of slaves expressly. North Carolina had done the same in substance. Slavery discourages arts and manufacturing. The poor despise labor when they know there are slaves to do it. Every master of slaves is born a petty tyrant. They bring the judgment of Heaven on a country. As Nations cannot be rewarded or punished in the next world, they must in this. By an inevitable chain of causes and effects, Providence punishes national sins by national calamities."

Not all delegates were happy with the final product. 3 high profile delegates refused to sign it: George Mason (Virginia), Edmund Randolph (Virginia), and George Mason (Virginia), and Elbridge Gerry (Massachusetts).

The Constitution must not be looked at merely for what it says. The Constitution can only truly be appreciated for what it embraces. Our Founding Fathers, who were immensely well-read and intelligent men, recognized and embraced the most productive and fairest philosophies regarding freedom, representation, government, markets, and laws and sought to embody them in our Constitution. The particular drafting of the Constitution, therefore, addressed the need to embody each particular philosophy for our new nation. First and foremost, the Constitution was designed to put into practice the principles laid out in the Declaration of Independence. It was designed primarily to secure the individual's God-given, unalienable rights. After all, it was the Declaration of Independence which laid the principles which were to guide our independent nation and therefore represented our national values.

The Constitution was intended to be timeless. It was intended to withstand the test of time and establish a government that would survive eternal (that is, as long as its people remained moral and ethical and of course, beholden to the Constitution). One of the biggest debates today, especially because of the condition we find ourselves in as a nation, is whether the Constitution is indeed timeless or was it just the starting place for those to "mold" as they deemed necessary. The answer to that is to use common sense. As we have repeatedly deviated from the Constitution, we have progressed further and further away from the positive ideals and productive values that made our country great. The biggest argument that liberal-minded people today make is that the Constitution is out-of-date, out-of-touch with the American people, and ineffective to meet our growing diversity and our evolving society. They argue that the Founders are outdated and that they have lost relevance. They say all these things because they believe that our Founding Fathers were products of their era and could not foresee the societal change that has evolved in this country. Nothing could be farther from the truth. Our Founders absolutely understood how the society would develop. The men who gave us the greatest nation on Earth weren't just a couple of guys who went to the Constitutional Convention in 1787 to hammer out the wording of a Constitution that would be binding on all the states. These men were visionaries. These men did their homework. They were deeply devoted to creating a nation that would stand the test of time. They wanted to come up with a foundation, a Constitution, that would not wither with the times. And so for that purpose, they studied all the failed regimes of history and they looked at all the constitutions and founding documents of other nations and studied the reasons why they were unable to last long. So, there is nothing that we've seen in our developing history that other nations haven't dealt with and nothing that our Founders weren't able to foresee. As Machiavelli wrote: "Whoever wishes to foresee the future must consult the past; for human events ever resemble those of preceding times. This arises from the fact that they are produced by men who ever have been, and ever shall be, animated by the same passions, and thus they necessarily have the same results."

The problem with ignoring history is that each time history repeats itself, the price goes up. The stakes are higher. From their studies of history's failed regimes, they came up with core principles that are absolutely vital to prevent this country from going down those same paths. They were wise enough to predict and to warn us of what would happen should we fail to honor and respect those principles. And there is nothing we see here today in this country that the Founders have not written about or warned us about. All we need to do is take the time and make the effort to read the legacy of documents they have left us. The principles and concepts that the Founders gave us are the perfect template for a successful government and a successful and honorable nation are timeless.

In order to understand our Constitution and other founding documents, we Americans need to understand what issues concerned the individual states at the time of our founding. We need to understand the issues on the minds of the Framers in crafting our new nation and where they looked for guidance and vision and solutions. The states were concerned with their sovereign power and their reluctance to give any of it up. Most states also were concerned with their right to embrace their religious heritage. All states except for three wanted to make sure that our new nation, which proclaimed that "All Men are Created Equal" would be rid of the injustice that was slavery. In drafting a document that would bind all the states into a unified nation (a union of states), and do so harmoniously and to meet their legitimate expectations, the Founding Fathers had to address the following fundamental questions: How to divide the power up as between the States and the Government? How much power should the government have? How much will it need in order to be effective? What is the legal basis of our fundamental rights? Do our rights come from God or from the government? What is the proper foundation to protect human rights? How to make sure that fundamental freedom is not burdened by the government? How should the government be structured? How can power remain with the people and be checked from abuses? What is the proper system to represent the voice of the people? How should the individual states be represented in the government? Each of these issues is critical in understanding how our nation was created. Our national heritage stems from the decisions these men made in 1787 with respect to these issues.

The goal of the Founders at the Convention of 1787 was to reach a consensus or general agreement on concepts and principles that the Constitution should embrace rather than compromise. They wanted to reach a consensus on what the Constitution should provide rather than compromise. So before they went into a voting session, they made sure that they thoroughly discussed and debated each issue. After almost 4 months of such debate, they were able to reach a general consensus on just about everything - except the issues of slavery, proportionate representation, and regulation of commerce. These three issues eventually needed to be resolved by compromise.

The Founders honored their goal and resolved most issues by consensus rather than compromise. As "compromise" often reflects a tone of defeat and submission (it's been called a "lose-lose scenario since both sides lose something they hold as important), the strength of the Constitution is that its provisions eventually and predominantly arose out of consensus. The Constitution was the product of extreme patience on the part of our Founders as each used reason and logic to bring the minds of the delegates into agreement. They wanted to make sure that the absolute soundest principles and concepts were adopted for the type of free and fair nation they had envisioned. Not one of the Founding Fathers could have come up with the perfect Constitutional formula to create a stable nation representative of the people and protective of their rights by himself, and the delegates who attended the Constitutional Convention in 1787 knew this.

| Political Speech is a Constitutional Right ... | Our Founding Principles, Op-Ed & Politics | Greg Dority Discusses the Economy |