Stacked Against, Part One: When prosecutors stack charges against a defendant, it can mean a lifetime behind bars | Eastern North Carolina Now

First installment in a 3-part series by the Carolina Public Press

“Stacked Against” is a multi-part series from Carolina Public Press examining charge stacking in North Carolina and its role in plea bargaining and disparities in sentencing.

In Part I, Jacob Biba reports on the experience of Terence Smith, a Black man from Winston-Salem sentenced to more than 50 years in prison for his role in a failed drug deal. Initially charged with only two crimes, prosecutors tacked on five more charges after Smith turned down a 10-year plea deal.

Terence Smith went numb when he saw his former drug dealer in a hospital bed in the courtroom. It was the opening day of Smith’s trial in Winston-Salem in March 2001. Smith, who was 18, was facing seven felony charges for his role in an armed robbery and shooting that left three people injured. Clarence Hart, a local drug dealer, would be paralyzed for life. If convicted on all counts, Smith knew he could be sent to prison for at least 50 years — a lifetime behind bars.

The police were searching for Smith, so he turned himself in after the incident, in February 2000. At first, prosecutors charged him with two crimes: armed robbery and attempted armed robbery. Based on the victims’ initial statements to investigators, Smith didn’t fire the gun nor did he commit the robbery, according to court documents. But he did bring the shooter, Kevin Anderson, to the apartment that night. This meant that Smith, who prosecutors also believed was aware of Anderson’s alleged plan to rob Hart, could be criminally liable as an accomplice.

Smith remained jailed in the Forsyth County Detention Center until his trial.

Nearly eight months after his arrest, the state offered Smith a deal: If Smith pleaded guilty to the two charges and testified against Anderson, he would spend the next 10 years in prison. If he turned this deal down and went to trial, he’d face five more charges, including attempted first-degree murder and multiple assault with a deadly weapon charges — the same charges Anderson faced. Jim O’Neill, the Forsyth County assistant district attorney prosecuting Smith, also warned that he would seek an even longer prison term by pressing the judge to “boxcar” Smith’s sentences — or run the sentences back-to-back — for more than 50 years if convicted.

The 10 years set out in the deal also felt like an eternity to Smith, who believed he had played only a small role in the crime and had no knowledge of Anderson’s plan to rob Hart. Though Smith had brought Anderson to Hart’s that night, he did so to merely buy a small amount of marijuana from Hart, Smith told Carolina Public Press in a phone interview from Pasquotank Correctional Institution in Elizabeth City. He didn’t know Anderson had a gun until Anderson first aimed it at Hart. Smith also didn’t take part in the shooting or robbery, he said, since he fled before the shooting occurred.

Smith, believing he was innocent, turned down O’Neill’s offer, despite the threat of additional charges and decades more prison time.

Commonly known as “charge stacking,” charging defendants with more crimes if they turn down a plea deal — or promising to drop charges if the deal is accepted — is a standard practice employed during plea bargaining to increase prosecutors’ leverage. While proponents believe the plea bargaining process increases convictions and makes the courts more efficient, there is a more harmful side to this practice, especially when charge stacking is involved. Critics believe the intimidating nature of plea deals forces defendants to give up their constitutional right to a jury trial or face a longer prison term.

“There’s no statute of limitations on criminal activity and there is nothing in the statutes that prevents a prosecutor from charging someone with conduct that they were not initially charged with,” Ben Finholt, director of the Just Sentencing Project at Duke Law School’s Wilson Center for Science and Justice, told CPP. “Because of that, prosecutors sometimes use the threat of additional charges as part of their coercive state power to drive people into plea deals.”

Critics also say racial bias, or the disparate treatment of people based on their race, may be at the center of many of these plea deals.

“Black defendants in drug cases, for instance, are less likely to receive favorable plea offers that avoid mandatory minimum sentences and, as a result, receive higher sentences for the same charges as white defendants,” the American Bar Association’s Plea Bargain Task Force wrote in a report published this year. “The same is true for gun cases, in which Black defendants are more often subjected to charge stacking.”

In 2019, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the NAACP, called for a ban on charge stacking, writing, “The stacking of charges has become standard practice to build such a horrifying potential sentence, that even actually innocent people will be intimidated into pleading guilty.” And if they do go to trial and are convicted, then they often face a “trial penalty” — the difference between what prosecutors offered in the plea deal and what’s delivered at trial — meaning a longer prison term.

“Everybody knows that if you go to trial, your sentence will be longer than if you plead guilty,” Carissa Byrne Hessick, a professor at the University of North Carolina School of Law and author of “Punishment Without Trial: Why Plea Bargaining Is a Bad Deal,” told CPP. “That’s the major premise behind plea bargaining — we give folks a discount if they plead guilty, and we give them a penalty if they insist on going to trial.”

A failed drug deal

The day that changed Smith’s life happened on Feb. 5, 2000. Just before midnight, Smith burst out the backdoor of Hart’s duplex apartment and started running as fast as he could. It was Saturday night, and by the time the first shots rang out, Smith was already out of earshot, he said, sprinting through the snow and ice leftover from a winter storm that passed through Winston-Salem more than a week earlier. When he finally arrived at his friend Reggie Roberts’ house 10 minutes later, Smith was panicking and completely out of breath.

Roberts, who was a few years older, knew Smith well enough to realize something awful must have happened. Smith was visibly shaken, Roberts told an attorney preparing a motion for appropriate relief for Smith that was filed in 2013 and denied in 2015. But when Smith finally calmed down and explained what happened, Roberts was both shocked and confused — he couldn’t understand why Smith would even be hanging out with Anderson in the first place. To Roberts, who thought of Anderson as a troublemaker in school, Smith and Anderson couldn’t have been more different.

According to Smith, he and another good friend, Kem Corpening, showed up at the Innkeeper, a small, nondescript motel where teenagers and 20-somethings in Winston-Salem often gathered to party. Corpening had been invited by Anderson earlier that day, Smith said, but when he and Corpening arrived, the scene wasn’t much more than several people hanging out in a motel room drinking and playing cards. Anderson was also there in the motel room. After being at the Innkeeper for close to an hour, Smith and Corpening left with Anderson. According to Smith, Anderson wanted to buy some marijuana, so they hopped in the car and headed to Hart’s apartment a few miles away.

When they arrived at Hart’s apartment, Corpening went inside first. Smith and Anderson stayed in the car. According to Smith, Corpening came back outside and told Smith and Anderson to go in around back, while Corpening went to the store. When Smith and Anderson got to the backdoor, Hart was holding it open, and both Smith and Anderson walked in.

Smith knew Hart — he was at Hart’s apartment almost every day, buying small amounts of marijuana from Hart, according to court records. Smith and Hart were friendly with one another but not friends, according to Smith. Anderson, wanting to buy a quarter pound of marijuana, had never been to Hart’s home, nor had the two ever met.

After buying a small bag of marijuana from Hart, Smith went to the bathroom, he said. When he returned, he found Anderson and Hart arguing over the amount of marijuana Hart was selling him — Hart was actually shorting him, according to trial testimony — and then Anderson pulled a gun on Hart. Shocked and in fear, Smith yelled, “What you doing,” to Anderson, but Anderson then pointed the gun at Smith and told him to stay out of it. When Anderson turned the gun back toward Hart, Smith ran outside, he said.

After Smith ran, Hart ran, too, and Anderson shot him in the back, according to court records. Right after, Anderson fired more shots, and two of Hart’s friends who were watching television in the next room were also injured. Joshua McCaskill was shot in the leg, and a bullet grazed Tamika McMoore’s forehead. Anderson struck Hart in the head with his gun after he shot Hart, Hart testified at trial, and his money and jewelry were stolen. A bullet lodged in Hart’s spine paralyzed him from the torso down.

The Winston-Salem Journal published a story naming Anderson and Smith as suspects the following week. Both Smith and Anderson turned themselves in and were charged.

A common practice and a life sentence

More than 20 years later, Smith is still confused about the circumstances surrounding his plea deal. “Without ever quite understanding how (nor why, to this day), I was simply charged with more offenses if I didn’t agree to this plea is still befuddling,” he wrote in a recent journal entry he shared with CPP. “Had I partook in these accused events, why wasn’t I charged with them from the very beginning also?” If he actually shot and robbed Hart and the other victims, or was even part of Anderson’s plan to do so, why wasn’t he charged right away with those crimes, Smith wondered.

Plea deals and the threat of stacked charges and enhanced sentences aren’t uncommon. In 2018, 90% of federal criminal cases in the United States were resolved because the defendant pleaded guilty, according to the Pew Research Center, a think tank based in Washington D.C. Data in North Carolina is limited, but an analysis of approximately 375,000 cases resolved between 1998 and 2010 showed that plea deals accounted for the closure of 96% of cases. The remaining cases were either dismissed or went to trial.

“Charge stacking and plea bargaining make it very easy to convict someone — much easier than it used to be,” Hessick said. “So, we shouldn’t be surprised, right? If we make it easy for people to do something, they’re likely to do it a lot more often.”

Ease of conviction is just one reason for prosecutors’ reliance on plea deals. They also don’t require nearly the same amount of time and expense a trial does, allowing prosecutors to clear cases faster and more efficiently without burdening the courts.

But critics believe one consequence of the criminal justice system’s strong embrace of plea bargaining is that it undermines defendants’ constitutional right to a jury trial.

“If the drafters of the Constitution learned, essentially, that people are being sent to prison for long periods of time without being able to plead their case in front of their community, they would be horrified by that idea,” Finholt said.

But going to trial often means spending even more time in prison if convicted, especially when more charges are stacked against a defendant. While the trial penalty is difficult to quantify in years, one study published in 2017 found an 11-year sentence differential between plea deals and jury trials for murder cases. Other studies have found trial penalties to be three times more in fraud cases and eight times higher for embezzlement, burglary and breaking and entering.

In May, a coalition of 24 criminal justice organizations, scholars, activists and formerly incarcerated people launched an effort to end the trial penalty and what the group describes as a coercive plea bargaining process.

“This Coalition — which spans the ideological, political, and professional spectrum — will breathe life into the criminal legal system by identifying and dismantling the laws, policies, and practices that have undermined the vision of the Framers,” Martín Sabelli, the coalition’s cofounder and former president of the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, said in a news release. “Forty years of coercive plea bargaining is enough. It is time to restore the balance that protects liberty and freedom.”

By turning down the plea deal, not only did Smith face a lengthier prison term because of the additional stacked charges, but he also had to contend with a prosecutor who begged the judge to run Smith’s sentences consecutively.

“Your honor, I would implore you to aggravate their sentences and run them back to back, boxcar, because what they did back on February the 5 of 2000 was give C.J. Hart a life sentence, and now they deserve exactly what they gave him,” O’Neill said to Judge Michael Helms in an effort to further extend Smith’s and Anderson’s sentences. “And it sends a message. If you do something like this, you’re going to be caught, you’re going to be tried, and you’re going to be convicted. When they come in front of a judge like you, the punishment is going to be severe.”

In 2022, O’Neill, who is now the Forsyth County district attorney, told the Winston-Salem Journal that “the best place for a violent criminal, who wants to hurt you and your loved ones is behind bars for as long as humanly possible.”

O’Neill did not respond to a request for comment.

In Smith’s case, the trial penalty was real as were O’Neill’s warnings during the plea bargaining process. Not only were the charges stacked against Smith, six of his sentences were, too, meaning he’d be spending the next 51-66 years in prison. At the earliest, Smith will be 69 years old when he’s released.

According to Finholt, whose work and research focuses on excessive sentencing and racial disparities in sentencing, one of the main issues related to charge stacking is that it can land people, like Smith, in prison for decades when they don’t need to be in prison for decades.

“Terence (Smith) is a great example,” Finholt said. “I do not believe that there’s any reason for Terence to spend 50 years in prison. But because of charge stacking, the state and the taxpayers of North Carolina have had to pay a ton of money to keep him housed when that was totally unnecessary. And so, each instance of charge stacking increases the burden on the system.”

In 2011, Joshua McCaskill and Tamika McMoore, the two other victims from the 2000 shooting at Hart’s apartment, spoke to investigators from North Carolina Prisoner Legal Services looking into Smith’s case. Both McCaskill and McMoore acknowledged, and again later in signed affidavits, that Smith did not hurt them or anyone else at Hart’s apartment that night. They also said Smith received too much prison time.

When investigators met with Hart around the same time, Hart asked them, “What happens when I say what I say?” He then went on to recall what happened the night of the incident, how Anderson pointed a gun at him, how he ran, was shot, and then passed out, according to a signed affidavit from Vernetta Alston, now District 29 representative, who was one of the investigators who spoke to Hart. In her affidavit, she stated, “Mr. Hart did not implicate Mr. Smith in his account of the shooting.”

Anderson, who is incarcerated at Warren Correctional Institution in Manson, did not comment. A recent call he made to CPP was disconnected. At trial, Anderson presented an alibi defense and claimed he never went to Hart’s apartment the night of the incident.

‘How do you get two shooting charges for one bullet?’

Seeing Hart in that hospital bed during the opening day of Smith’s trial in Winston-Salem in March 2001 caused Smith to go numb. He said the five-day trial was all a blur and that it wasn’t until his former teacher and mentor, Tony Burton, muttered the words “Oh, God,” after Smith was sentenced, that he came to and realized what just happened.

“Terence (Smith) is being punished for his whole entire life because he walked in the door with a guy with a gun and because he was 17 years old,” Mark Rabil, Smith’s trial attorney, told CPP. “And there’s really no other way to look at it. Prosecutors know they can win because they have damaged people, like in this case, Mr. Hart, who they bring in there in a hospital bed and tear at the hearts of the jury. It was just a completely unfair scenario.”

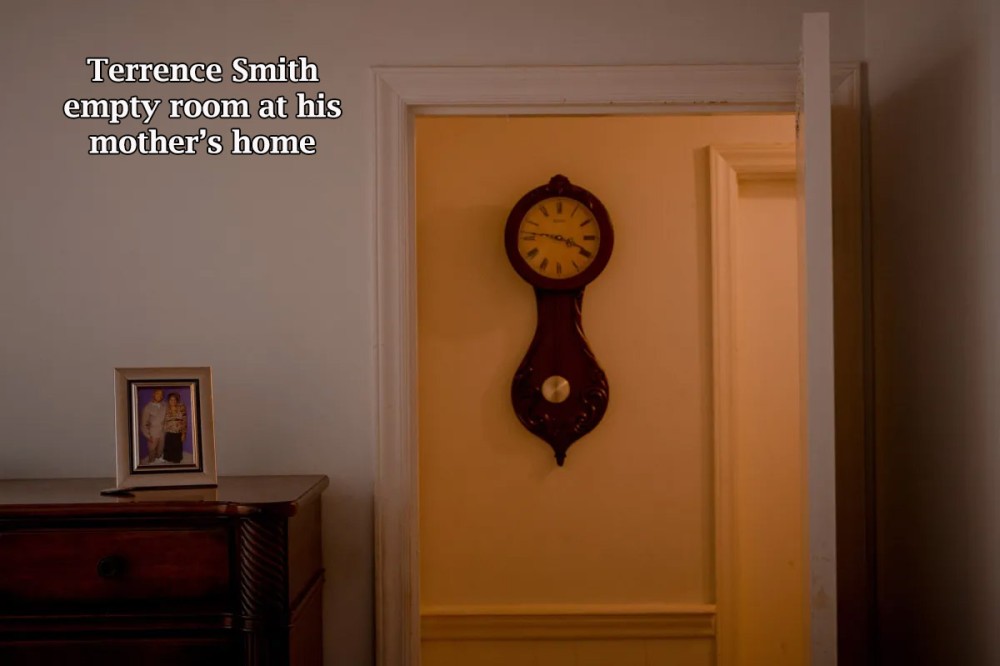

A picture of Deborah and Terence Smith is seen in the bedroom of Terence Smith in Deborah Smith’s home in Winston-Salem on April 27. Terence Smith has been incarcerated for over two decades of a 51- to 66-year year sentence for his involvement in a nonfatal shooting when he was 17 years old. Photo: Mike Belleme / Carolina Public Press

As a result of his conviction and sentencing, Smith entered prison indignant but quickly vowed to move on and better himself. He started reading religious and self-help books his aunt Belinda sent him. He’s generous with others that he’s incarcerated with, family members told CPP, and he’s worked in the prison laundry room and as a canteen operator, which is considered a position of trust in prisons. He also began studying the Bible and drawing self-portraits and writing poems for his mother, Deborah. He’s completed numerous vocational classes like electrical wiring and human resource development, all of which have helped him overcome any resentment he had regarding his sentence.

But in 2012, that bitterness began to resurface when Hart was shot and killed in another failed drug deal. According to initial news reports on Hart’s killing, Madyson Renegar, a 19-year-old white woman, had shown up at Hart’s home and the two got into an argument over money. Months later, another report said Renegar had shown up to buy marijuana and the two had gotten into a fight over Hart’s son, whom Renegar accused Hart of abusing. In that account, Hart started hitting Renegar, so she grabbed Hart’s gun, which was nearby.

Hart was shot in the back of the head and in the left arm, according to the medical examiner’s report. By the time Hart was shot and killed, both his legs had been amputated and he weighed around 75 pounds.

After the shooting, Renegar was arrested and offered a deal. She pleaded guilty to second-degree murder in Forsyth County Superior Court and was sentenced to 12-15 years in prison. Renegar is projected to be released next year.

When Smith learned the details surrounding Hart’s death and Renegar’s sentence, he began to question what he considered the injustice of his charges and sentencing.

“You’ve got two shots, and she got one charge,” Smith said. “In my case, he was shot once, and I got two shooting charges. How do you get two shooting charges for one bullet?”

According to Smith’s current attorney, Johanna Jennings, founder and executive director of the Decarceration Project, a Durham nonprofit dedicated to addressing inequities resulting from mass incarceration, racial bias may be at the center of the disparity in sentencing between Smith and Renegar.

“It’s pretty hard to look at that and not see that race could very likely have played a factor,” Jennings told CPP.

Jennings also believes racial bias played a role in Smith’s decadeslong sentence, one she believes may have been fueled by the superpredator myth of the 1990s.

“We had this narrative, a really false and pernicious narrative, in the 1990s, about superpredators, which is basically young, Black youth or young people of color — teenagers — kind of pathologizing them and deciding that they’re all sociopaths or psychopaths who are going to go out and commit a bunch of violent crime,” Jennings said.

The fact that Smith, who was 17 when the crime occurred, received a very similar sentence to Anderson, who Jennings said was more culpable given he “actually shot and robbed people,” suggests to her that superpredator rhetoric may have played a role. “At the time, people may have been seeing all Black youth as the same, as dangerous, as threats to community safety, without looking at the differences in circumstances or the nuances of the case, the differences in culpability, the differences in mitigation,” she said.

Deborah Smith poses for a portrait in her son Terence’s room in her home in Winston Salem on April 27. Her son, Terence Smith has been incarcerated for over two decades of a 51- to 66-year sentence for his involvement in a non-fatal shooting when he was 17 years old. Photo: Mike Belleme / Carolina Public Press

The circumstances surrounding Hart’s death and Renegar’s sentence have been difficult for Smith’s family to comprehend. “She killed somebody. My son did not. So where is the justice?” Smith’s mother Deborah Smith told CPP in an interview at her home in Winston-Salem.

Deborah Smith actually pushed her son to take the plea deal, she said, as did other family members, describing her son’s sentence as cruel and unjust and “too far-fetched to even think about.” Hopeful her son will be released early, Deborah Smith has a room made up for him in her home and a car ready for him to drive. They speak every Sunday. Her nickname for him is T-Boogie.

Recently, Smith wrote about his own disbelief regarding his trial and how his childhood would ultimately end with him entering prison, where he would not only transition into adulthood but would have to grapple with fear, anger, confusion and ongoing trauma.

“None of it seemed real as the recurring nightmare was only beginning,” he wrote.

In upcoming parts of this series, we’ll look at the effect charge stacking has had on the lives of Smith and his family, as well as others who have experienced excessive sentences as a result of the practice. We’ll also look at the rationale for plea deals and the role they play in promoting efficiency in the courts. We will also speak to legal experts and scholars and look at the history of charge stacking and its use in the state and elsewhere in the country. We will also discuss potential solutions that could curb its use and promote more just sentencing outcomes.

Have a question about this story? Do you see something we missed? Send an email to news@carolinapublicpress.org.

|

Charli Decker

|

|

I understand your desire to normalize Marc Elias' bastardization of our election laws, funded by Soros, to making cheating easier. Just accept that true Americans are going to fight for fair elections. Just as Ukrainians did in the Orange Revolution or Germans did in suing to succesfully overturn the fraudulent elections in Berlin two years ago. Unfortunately, American courts are much more gunshy of addressing electoin fraud than European courts.

|

|

I understand your desire to normalize trumpís behavior. Just accept the results.

|

|

OH? Like Al Gore, Hillary Clinton, and Stacey Abrams, among many such Democrats, "accepted the results"???? If the election is honest, the results will be accepted by conservatives. Changing the rules at the last minute, often contrary to law, is a Democrat specialty, especially in 2020 with Democrat shyster Marc Elias, funded by Soros, running wild. One major project of conservatives is laying the groundwork for honest elections in this country, and what is interesting, the methods conservatives are using fit very closely with the rcommendations of former Democrat president Jimmy Carter and his commision on free and fair elections, one of which was to minimize mail in voting because it is the easiest way for dishonest persons to cheat.

|

|

Just make sure you accept the results. Thatís really all I ask. I donít think I can take 4 more years of whining be-otch behavior. So unseemly.

Complaining is fine. But no more fake electors, violence or threats. |

|

Little Bobbie clearly has not been looking at the polls recently. The people against Trump who are dangerous to our democracy are the politically corrupt prosecutors who are coordinating with the Biden White House against Biden's political opponent. That is election interference. When the Biden DOJ sent a humorist to prison for "election interference" for a satire on the way Democrats were corrupting our voting laws, they have opened the door very wide to prosecute those in our judicial system who are engaged in much more substantial election interference like Fani Willis, Merrick Garland, Jack Smith, and similar scoundrels.

|

|

Everyone's against him....his struggle unimaginable....Oh the humanity....

|

|

There he goes again. Racist troll Bigot Bob tries to make everything about race. The abuse of the courts against President Trump is not about race, it is about politics and misusing the courts to try to destroy a political enemy. What Biden and his minions are doing with the courts against Trump is exactly the same thing that Putin did with the courts against Alexsi Navalny and other adversaries and what Stalin did with the courts against numerous political enemies. This is the threat to our democracy. Biden and Putin are two peas in a dictatorial pod.

|

|

White billionaire canít get a break, amIright?

|

| Surging right leads in polls for Portugal's election Sunday as Socialists falter | Editorials, Beaufort Observer, Op-Ed & Politics | End Of Primary |

As I must prepare on the odd chance he wins. Thatís how America works. Nothing less will be accepted