In Difficult Times Good People gravitate towards Absolute Truth

Northwestern Dean Discusses Digital Revolution, Future of Media in Hayek Lecture

Publisher's note: This post appears here courtesy of the Carolina Journal, and written by Brooke Conrad.

The digital revolution has slashed profits for companies in the business of journalism, leaving the industry to reassess a longstanding yet faulty business model, says Charles Whitaker.

Four decades ago, the student rate for an annual subscription to Time magazine was $200, said Whitaker, dean of Northwestern University's Medill School of Journalism, Media, Integrated Marketing Communications.

Today, a regular subscription to the magazine is $40. But it's consumers who'll determine its real value.

Whitaker spoke Monday, Feb. 17, as part of the Hayek Lecture Series at Duke University. The lecture series features prominent scholars and writers, who address issues about our economy and our society.

In early America, newspapers, for instance, catered to an elite audience who could afford a subscription. That changed in the early 19th century with Benjamin Day's "penny press," which relied more heavily on advertising than subscriptions, opening readership to the masses.

From there, journalism depended on what Whitaker calls the "exposure business model" - a three-legged stool involving publisher, consumer, and advertiser. Through this model, the consumer gets content dirt cheap, and the advertiser shoulders the bulk of the costs.

"That's not how the sneaker business works," Whitaker said. "The sneaker business produces the thing really cheaply and then sells it for 10 times what it costs to produce."

As recently as the 1990s, publications were still reporting 20% profit margins. Unlike the seeming overnight conversion from vinyl to CD, the newspaper industry adapted more slowly to the digital revolution. One reason was the "halo effect" of print advertising. Print ads feel as if they're part of the news-reading experience, and they absorb more subconscious attention. When a reader opens a website, they're more likely to feel annoyed and "x" out all the advertisements.

Another revenue stream, later decimated by Craigslist, were classified ads. Even though the cost of each ad unit was relatively small, aggregating them could produce a sizable profit.

"A publisher friend of mine said classified ads were like found money. You just raked it in," Whitaker said.

Traditional advertising couldn't compete with Google ads, which provided useful data about consumers' habits. Coupon revenue also took a hit. On Sundays and Wednesdays, typically, newspapers were chock-full of coupons, later slashed due to the rise of big-box stores and Amazon.

Today, the digital age has atomized online content and divorced it from major outlets, giving rise to myriad "news" outlets pushing their content through social media.

"This fake news looks real and it comes to us out of nowhere. Of course, we absorb it and begin to think it's real. It calcifies our positions and makes compromise impossible," Whitaker said.

Digital media thrives on public discord. Advertisers will pay publishers by the click, and more controversy equals more clicks. Still, the business model is unsustainable, he said, and digital advertisers only pay about a penny per click, relatively nothing compared to what they'd pay for a page in a magazine.

So, can the news media be saved?

Some outlets today rely on billionaire funders, such as the Washington Post, owned by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos. Others rely on foundations and nonprofits. But, Whitaker said, this third-party business model isn't a formula for success.

The modern media landscape does have advantages: lower production costs and fewer industry gatekeepers. But that changing landscape also means journalists must become more dynamic in their skills as jobs become more competitive. They have to be able to operate a camera or deliver a newscast on the spot, for example.

Increased media literacy may help, Whitaker said. Today, many people don't understand the codes of conduct by which journalists generally operate - what it means to speak "off the record," the difference between the news and editorial pages, and the fact reporters typically don't pay money for their sourcing.

Increased media literacy won't be the industry's saving grace, Whitaker said. But it's still important that people value the product and the importance of a free press.

"We need more people invested in what journalism is."

Go Back

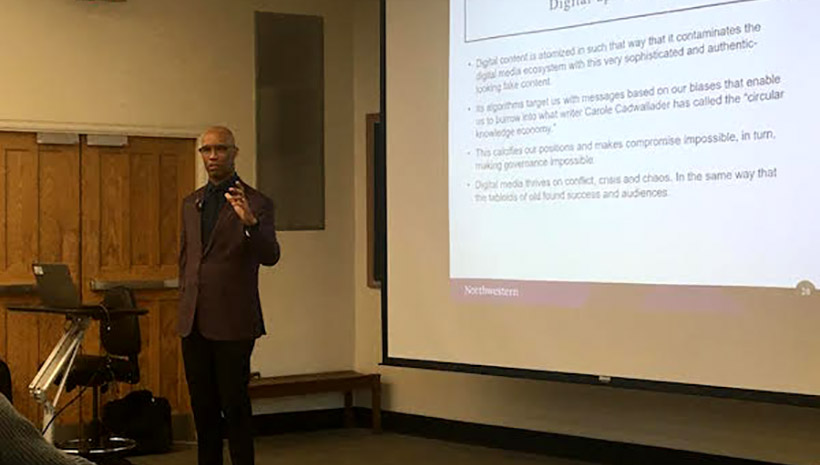

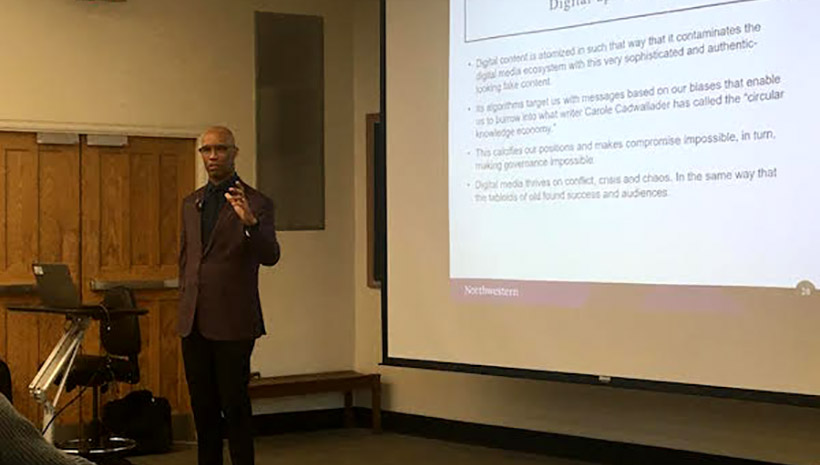

Charles Whitaker, a dean at Northwestern University, speaks Monday, Feb. 17, as part of the Hayek Lecture Series at Duke University. | Photo: Brooke Conrad/Carolina Journal

The digital revolution has slashed profits for companies in the business of journalism, leaving the industry to reassess a longstanding yet faulty business model, says Charles Whitaker.

Four decades ago, the student rate for an annual subscription to Time magazine was $200, said Whitaker, dean of Northwestern University's Medill School of Journalism, Media, Integrated Marketing Communications.

Today, a regular subscription to the magazine is $40. But it's consumers who'll determine its real value.

Whitaker spoke Monday, Feb. 17, as part of the Hayek Lecture Series at Duke University. The lecture series features prominent scholars and writers, who address issues about our economy and our society.

In early America, newspapers, for instance, catered to an elite audience who could afford a subscription. That changed in the early 19th century with Benjamin Day's "penny press," which relied more heavily on advertising than subscriptions, opening readership to the masses.

From there, journalism depended on what Whitaker calls the "exposure business model" - a three-legged stool involving publisher, consumer, and advertiser. Through this model, the consumer gets content dirt cheap, and the advertiser shoulders the bulk of the costs.

"That's not how the sneaker business works," Whitaker said. "The sneaker business produces the thing really cheaply and then sells it for 10 times what it costs to produce."

As recently as the 1990s, publications were still reporting 20% profit margins. Unlike the seeming overnight conversion from vinyl to CD, the newspaper industry adapted more slowly to the digital revolution. One reason was the "halo effect" of print advertising. Print ads feel as if they're part of the news-reading experience, and they absorb more subconscious attention. When a reader opens a website, they're more likely to feel annoyed and "x" out all the advertisements.

Another revenue stream, later decimated by Craigslist, were classified ads. Even though the cost of each ad unit was relatively small, aggregating them could produce a sizable profit.

"A publisher friend of mine said classified ads were like found money. You just raked it in," Whitaker said.

Traditional advertising couldn't compete with Google ads, which provided useful data about consumers' habits. Coupon revenue also took a hit. On Sundays and Wednesdays, typically, newspapers were chock-full of coupons, later slashed due to the rise of big-box stores and Amazon.

Today, the digital age has atomized online content and divorced it from major outlets, giving rise to myriad "news" outlets pushing their content through social media.

"This fake news looks real and it comes to us out of nowhere. Of course, we absorb it and begin to think it's real. It calcifies our positions and makes compromise impossible," Whitaker said.

Digital media thrives on public discord. Advertisers will pay publishers by the click, and more controversy equals more clicks. Still, the business model is unsustainable, he said, and digital advertisers only pay about a penny per click, relatively nothing compared to what they'd pay for a page in a magazine.

So, can the news media be saved?

Some outlets today rely on billionaire funders, such as the Washington Post, owned by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos. Others rely on foundations and nonprofits. But, Whitaker said, this third-party business model isn't a formula for success.

The modern media landscape does have advantages: lower production costs and fewer industry gatekeepers. But that changing landscape also means journalists must become more dynamic in their skills as jobs become more competitive. They have to be able to operate a camera or deliver a newscast on the spot, for example.

Increased media literacy may help, Whitaker said. Today, many people don't understand the codes of conduct by which journalists generally operate - what it means to speak "off the record," the difference between the news and editorial pages, and the fact reporters typically don't pay money for their sourcing.

Increased media literacy won't be the industry's saving grace, Whitaker said. But it's still important that people value the product and the importance of a free press.

"We need more people invested in what journalism is."

| Community Colleges Scramble to Graduate More Working-Age Students | Carolina Journal, Editorials, Op-Ed & Politics | Wheels of Justice Hit a Rut With Challenge of N.C. Certificate of Need |

Latest Op-Ed & Politics

|

illegal alien "asylum seeker" migrants are a crime wave on both sides of the Atlantic

Published: Thursday, April 18th, 2024 @ 8:10 am

By: John Steed

|

|

UNC board committee votes unanimously to end DEI in UNC system

Published: Thursday, April 18th, 2024 @ 7:54 am

By: John Steed

|

|

this is the propagandist mindset of MSM today

Published: Wednesday, April 17th, 2024 @ 3:04 pm

By: John Steed

|

|

Police in the nation’s capital are not stopping illegal aliens who are driving around without license plates, according to a new report.

Published: Wednesday, April 17th, 2024 @ 8:59 am

By: Daily Wire

|

|

same insanity that created Covid

Published: Wednesday, April 17th, 2024 @ 8:58 am

By: John Steed

|

|

Davidaon County student suspended for using correct legal term for those in country illegally

Published: Wednesday, April 17th, 2024 @ 7:23 am

By: John Steed

|

|

given to illegals in Mexico before they even get to US: NGOs connected to Mayorkas

Published: Tuesday, April 16th, 2024 @ 11:36 am

By: John Steed

|