Publisher's note: This post was created by the staff for the Carolina Journal, John Hood Publisher.

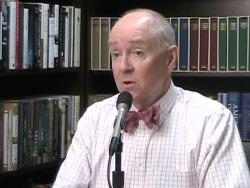

Managing Editor Henderson analyzes end of nine-year legal battle

RALEIGH - A nine-year legal battle pitting two siblings against the state of North Carolina came to an end this spring. The story, reported by Carolina Journal

beginning back in 2011, ends not only with a personal victory for Harriet Hurst Turner and her brother, John Hurst, but with a victory for those who believe that the effort of former Gov. Bev Perdue administration's to obtain the property without paying for it amounted to an unfair wielding of government power. CJ Managing Editor Rick Henderson discussed the issue with Donna Martinez for Carolina Journal Radio. (Click

here to find a station near you or to learn about the weekly CJ Radio podcast.)

Martinez: First, let's set the stage. Where is the property that we're talking about, and who are the key players here?

Henderson: It's in Onslow County. It's coastal property - about 300 acres - that is very close to the Hammocks Beach State Park. People may be familiar with Bear Island. It's in that general area there.

Martinez: And the players here?

Henderson: John Hurst and Harriet Hurst Turner, who are the grandchildren of John and Gertrude Hurst, who had been given access to the property, if you will, the run of the property, back in the 1950s by the person who purchased it back about 30 years before that - a physician based out of New York who had used the Hursts as guides and also as domestic workers, when they came down here duck hunting.

Martinez: Now, Rick, this is a huge piece of property - 238 acres. Why was there a dispute over this property ownership in the first place?

Henderson: What had happened was that the physician had given the property to John and Gertrude Hurst. They were African-Americans, and they'd become close friends with the physician, and what had happened was that they wanted to use the property - this piece of the property - to be a camping area and resort area for the association of black teachers. At the time, public education was segregated.

Martinez: This is back in the '50s?

Henderson: That's right. So public education was segregated. And they wanted to have a special resort area for members of that teachers association. And so, rather than giving the property to John and Gertrude, which is actually what originally was the plan, they said, "No, we'd rather have this set aside to be an area that black teachers could enjoy as a beachfront resort."

Well, what happened was, a separate corporation was formed to manage the property after the Hursts passed away. And the property of the corporation was given access to management rights over the property, but the Hursts also had access to use it for their own purposes.

As it turned out, once segregation ended, there was no need for a segregated beach anymore. And so the properties fell into disarray. And the group, called the Hammocks Beach Corporation, had a hard time generating revenue from folks like 4-H groups and things like that - enough to keep the island, and that area, or that beachfront area, in good repair.

Martinez: Is that the point at which Harriet Hurst Turner and her brother, John Hurst, decided that since the situation - society - had changed, and there were questions over how the property was then being used, they decided to step in and try to take it back?

Henderson: What actually happened was that in the 1980s, the corporation just basically said, "We can't live according to all of the stipulations in this deed," because the deed stated they couldn't sell the property, they couldn't make any improvements on the property without permission of the families.

And at this point, the family, the Sharpe family, which gave the property originally to the Hursts, had gotten out of it entirely and said, "We don't want anything more to do with this area."

And the Hursts tried to go into a negotiation with the Hammocks Beach Corporation to make this happen. But there was another party involved, and that was the State Board of Education, which got involved early on because the black teachers association was involved. And so the State Board of Education was sort of a fallback owner of the property, if everything else fell apart. This was in '86 that this started.

Martinez: So now, it sounds as if there are three entities that all think that they have some claim to this. You've got this corporation. Then you've got the state, through the State Board of Education. And now you've got Harriet Hurst Turner and her brother, John.

Henderson: And they wanted to make this thing work. They really wanted to have some sort of resort area that was accessible to different groups and the like, because it's a very beautiful piece of coastal property. The state, in 1986, as a part of this legal battle, the state got into a consent agreement and said, "You know what, we're going to renounce our interest in this. We're going to let the corporation work this out with the Hurst heirs."

And this went on for about another 20 years. And the corporation still couldn't make a go of it. And so, in 2006, the Hursts decided, "Well, OK, we need to see about getting this property back because it's really fallen into disrepair. It's not living up to the terms of what our grandparents were really looking for, even what the Sharpes, who originally owned the property, were looking for. So, we want to get it back because we don't think the corporation is capable of managing it properly."

Martinez: So that's when the very serious legal wrangling began?

Henderson: Right. Because what happened was, in 2006, the battle started. And, all of a sudden, the State Board of Education started expressing some interest in it. Now, there was a legal decision that was made in 2010, in which, at a jury trial, the jury awarded the property to John and Harriet and said, "You now manage the property."

Martinez: A victory for them.

Henderson: They thought. But the judge presiding over the trial, Superior Court Judge Carl Fox, stepped in and said, "No, we've got to let the state have a chance to take this over again if it wants to." Now, the state had renounced all interest in this on two separate occasions.

Martinez: That's odd.

Henderson: That is. What had happened is that attorneys working for the Department of Environment and Natural Resources, who worked for Attorney General Roy Cooper, had been meeting with State Board of Education members and had been convincing them that this was would be a great "get" for the state, to take over this property and add it to the Hammocks Beach State Park, which surrounds this particular little area of coastal property. And so, that just mucked the whole thing up, and it required the Hurst heirs to get involved in a big way and maintain their battle against, now the state, not the corporation.

Martinez: What happened after that? Because I would imagine that Harriet and John were thinking, "Hey, wait a second." A judge has said yes, indeed, it does belong to you. And now, it's the little guys battling the state of North Carolina.

Henderson: That's exactly what happened. And what happened was the Hursts say that our reporting actually helped explain their story, helped explain their role. It wasn't that they were trying to take property from the state. It was that the state was trying to take property from them.

Martinez: Right. And CJ began reporting on this back in 2011.

Henderson: That's right. And what happened, eventually, was that when Gov. Pat McCrory took over, there was new leadership at DENR, and they just started looking at things in a different way. They started working to negotiate a settlement with the Hursts. And they did.

And what happened was that The Conservation Fund Executive Director Bill Holman - [he] used to be DENR secretary, well known in environmental and legal communities - worked it out so that the state would purchase the property from the Hursts for $10.1 million. It would be used as a resort. So it would be improved as part of the park system.

Harriet Hurst Turner is very happy about that because she really wanted that original intent to be involved. And the family ends up being compensated for their land.

Martinez: So, they now have received - have they received it yet, this $10 million settlement?

Henderson: I believe that they've actually received that. The Conservation Fund provided some of the money because the state didn't have it all available right away. But they have indeed been compensated for it, and that long battle is over.

Martinez: So, Rick, what does this story say about government power and the role that the government can play in, really, taking control of people's property?

Henderson: Unless when you have situations where titles are messy, and there are any kinds of disputes between various parties, the government, quite often, can trump the little guy. Unless the little guy has champions on its side, to really make the right thing happen and to make sure that people's wishes are honored.