Publisher's note: This article, by Kathryn Kennedy , was originally published in ECU News Services.

East Carolina's first African-American graduate creates new memories as she and the campus celebrate 50 years since desegregation.

She's been called a hero, a role model, and is lauded for her groundbreaking achievement. But Laura Marie Leary Elliott, '66, doesn't see herself that way.

"I was a 17-year-old kid," she says. "I wanted to make my parents proud."

Humility aside, Elliott's arrival at East Carolina College in 1962 changed the campus forever, and forged a path for the thousands of African-American students attending ECU today.

Elliott wasn't privy to the details of how she was identified as the student to desegregate ECU. She certainly planned to go to college, and was valedictorian of her class at Pitt County Training School in Calico, a small community between Greenville and Vanceboro.

"Who's volunteering me for this?" she remembers thinking. "Everything was so hush-hush, I didn't even know what was going on. It was just one day I was packing my bags."

"I'm grateful to have the opportunity to write some new memories..." -- Laura Marie Leary Elliott photo by Jay Clark

"I'm grateful to have the opportunity to write some new memories..." -- Laura Marie Leary Elliott photo by Jay Clark

She recalls the decision being made for her by her parents very shortly before her freshman year was set to begin. The family worked with African-American physician and Greenville community leader Dr. Andrew Best to gain her admittance. Best came to know Elliott when he visited her high school to lecture on health issues.

"He took a shine to me," Elliott explains, smiling. "Said I was very intelligent, a nice young lady."

Still, Elliott was not eager to be an example.

"Mom was always hugging me and saying it was going to be OK," Elliott says of the days before her departure from home. "I believed her."

'Lonely and scary'

As an African-American student at ECU, Elliott was rarely taunted or insulted outright, she explains. She suffered instead from isolation.

"It was like I was in a robotic stage," she recalls. "Like slow motion. Go here, do this. It was lonely and it was scary. I didn't feel like I belonged."

Elliott never attended a football game or hung out in the student union playing cards. She lived off campus at first, with a pastor and then her aunt and uncle. Later she lived alone in Ragsdale Residence Hall after the young white woman chosen to be her roommate asked to be placed elsewhere. Professors didn't give her any trouble, but she doesn't recall them taking interest in her either, with a few exceptions.

Desegregation, she explains, was not an easy process. "It was publically smooth," Elliott says, "But privately, we were hurting."

It was an especially drastic change in environment for a young woman who grew up with 12 siblings. "I used to cry every year that I didn't want to go back," Elliott says. "And one of my sisters, she'd tell me that I had to. That mom and dad were counting on me."

The years did pass, and each one got a little easier. She found companionship as a small stream of African-American students trickled onto campus in her wake. Several of them have told her she was like "a mother hen" to those who followed.

"Me?" she says, and chuckles. "I was the one who was most scared!"

When Elliott left high school, she'd planned to become a nurse. However, her favorite instructor was a business professor, so she majored instead in business administration. That choice would serve her well in the decades to come.

Elliott went to work immediately after graduating from ECU in 1966, moving to Windsor to teach. Ready for a change of scenery, she relocated to Washington, D.C., in 1968 without a job, but quickly found one as an auditor with the U.S. Department of Justice. It was there that she met her husband, the late Allen R. Elliott, after joining a bowling league. They were married just three months later, in February 1971.

The couple would go on to raise two children, a son and a daughter, Reginald Allen Elliott and Rachel Marie Elliott. After a few more moves, Elliott landed a job with the U.S. Department of the Treasury. She worked there from 1987 until she retired in 2006 as a senior accountant.

'It didn't break me'

Throughout this time, Elliott says she neither spoke nor thought of East Carolina. Family members and friends would cheer their teams and wear their school colors proudly. Not Elliott. But she isn't bitter either.

"The experience wasn't what I wanted but it didn't break me," she says. "It made me a stronger person. I've had a lot of challenges through my life and this...helped."

In considering the decision her parents made to send her to an all-white college, Elliott stresses today that her parents were not "freedom fighters." And neither, she says, was she making "a bold protest."

"They were just wanting things a little bit better for their children," she says.

Elliott believes her parents were proud of what she accomplished, though they were never able to fully express that pride.

"They didn't want to make a fuss," she says. "Didn't want to stir up any resentment."

Elliott also never met

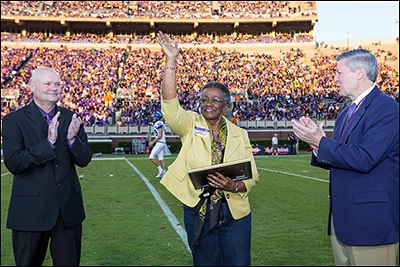

Elliott, center, was honored during ECU's homecoming Oct. 13. She was recognized during halftime of the game by ECU Board of Trustees chairman Bob Lucas, left, and ECU Chancellor Steve Ballard, right. She spoke with other alumni while visiting campus and rode in the Homecoming parade. photo by Jay Clark

the man who agreed to receive her at ECU in 1962 - former chancellor Dr. Leo Jenkins. However, at halftime during ECU's homecoming football game Oct. 13, she was recognized by Chancellor Steve Ballard and ECU Board of Trustees Chairman Bob Lucas. During her visit, Elliot spoke with other African-American alumni in the Ledonia Wright Cultural Center, and participated in the annual Homecoming Parade.

The events were organized in part by Vice Chancellor of Student Affairs Virginia Hardy '88 '93, and her committee charged with commemorating the 50th anniversary of desegregation. Hardy says Elliott is an important part of ECU's history, and the impact of her actions cannot be ignored.

"The relationship (between ECU and Elliott) was not the greatest," Hardy admits. "I wasn't sure she would come."

But Elliott said the decision to take part in the 50th anniversary commemorations was an easy one.

"I'm grateful to have the opportunity to write some new memories," Elliott says. "It's the little things that make me feel connected, and not just to the history but to the university."

Hardy says, "When Laura Marie Leary started her lonely journey at East Carolina, she did not see herself as a pioneer. But 50 years later, we know better. She is the face of change that was needed 50 years ago and the symbol of success and persistence that we still need today.

"She didn't know her classmates, but now she has us."

Elliott is scheduled

to return to campus at least once more this spring to take part in continuing 50th anniversary events.