Publisher's note: The author of this post is Katherine Restrepo, who is the Health and Human Services Policy Analyst for the John Locke Foundation.

Health care policy decisions usually come as federal dictates, so it's a rare opportunity when state legislators have full authority to grant North Carolinians more freedom over their health care options.

Repealing Certificate of Need (CON) laws is a perfect example. These laws require medical providers to weave through lots of red tape to expand services, build new facilities, or update medical equipment.

Who better than the government to know what's best for patients?

CON was originally mandated by the federal government as a way to cut down on underused services and to preserve access to health care in underserved areas, but Congress classified the law as a failure in the late 1980s and made these programs optional for states. If the feds recognized then that this law failed to deliver on its intentions, odds are that this is still the case.

With that said, here are three particular reasons why North Carolina's CON laws need to go:

1. Failure to control health care spending.

Duke University's Chris Conover and Frank Sloan conducted a

widely cited study to find out whether removing CON regulations on acute care, including ambulatory surgery and inpatient hospital and physician visits led to a surge in health care spending. Controlling for factors such as other forms of regulation and area competition, the authors found that an overall surge in spending did not happen. Mature CON programs may have contributed to a 5 percent spending reduction for acute care services, but they did not constrain overall spending per-capita. Put simply, since some states' CON programs don't monitor every service under the sun, it makes sense for health providers to acquire equipment or deliver care that isn't regulated.

2. Failure to uphold rural health care

CON does not help rural health care

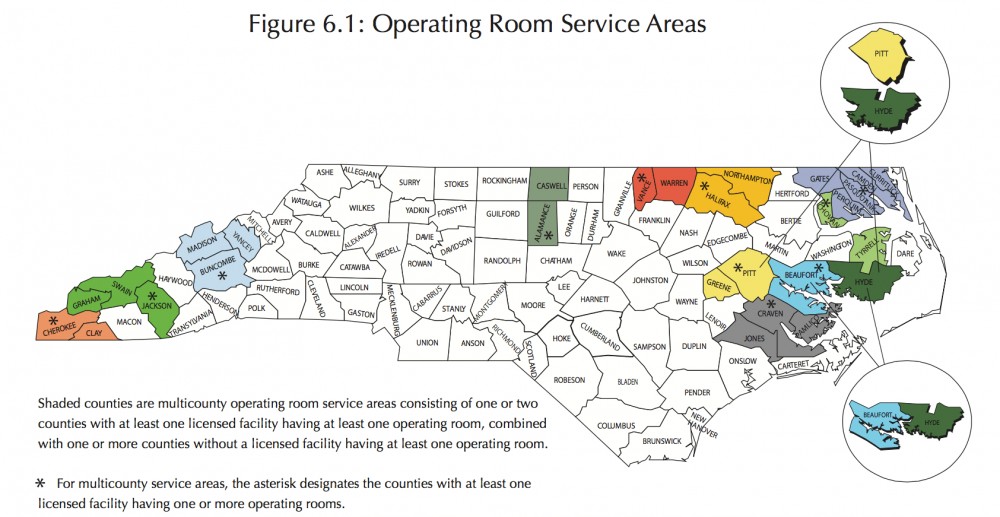

one iota. Just one contributing factor is the Sovietesque planning the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) uses when determining "needed" medical resources. Take operating rooms, for example. The map below shows that some operating room service areas are comprised of multiple counties, meaning that patients in one county without an operating room may have to travel long distances to access one.

The multi-county and regional resource allocation method also explains why there is such a large patient outmigration from rural areas to urban centers that possess the political and monetary clout to win approval for projects. As the

Harvard Business Review puts it:

These hospitals are caught in a vicious cycle: Rural patients with serious health problems are traveling to cities to seek care from medical specialists, causing revenue declines at rural hospitals and clinics, which respond by downsizing and offering fewer services, causing more patients to seek care in major urban centers.

3. A Dysfunctional Administrative Process

The CON process usually plays out in multiple health systems submitting competing applications to win approval by the state for a capital project that is considered "needed." In the end, there are winners and losers.

But it doesn't stop there.

Competing applicants can appeal an approved application. This results in patients being denied access to health care more quickly or in a more convenient setting.

What makes this law even more messed up is that

non-competing applicants can step in. Years ago, Triangle Orthopedic Associates (TOA), North Carolina's largest private orthopedic practice, and Duke University Health System filed competing applications for an MRI machine. TOA ended up winning the bid. While Duke didn't petition against the decision, a separate company, Alliance Imaging, did. It had previously provided MRI services to TOA and feared the loss of business that would result if TOA procured its own machine.

The CON process also induces hoarding. Word on the street is that it happens more often than not when health systems build only a portion of the total number of operating rooms authorized by the state — a convenient way to block competition and distort the state medical facility's projections of ORs that are "needed."

As the budget negotiations drag on, legislators have a choice. Derailing CON would boost North Carolina's overall health care freedom. Keeping the laws on the books will instead continue to

harm rural health care, burden patients with

higher costs,

protect hospitals from competition, and

stifle innovation in the health care sector.