December 15 was Bill of Rights Day. It marks the 221st anniversary of the day when the first ten amendments - our Bill of Rights - were ratified in 1791.

The Bill of Rights is among those documents classified as "Charters of Freedom." It belongs with the list that includes the Magna Carta, the Habeas Corpus Act, the English Petition of Right, the English Bill of Rights, the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, and the Virginia Declaration of Rights. We are reminded everyday of regimes all over the world where people enjoy no fundamental rights, no freedom of religion, no freedom of speech, no freedom of assembly. We read about abusive judicial systems that lack of guarantees of due process, jury trials, and protection against self-incrimination. And we hear about oppressive police states where unreasonable searches and seizures and cruel and unusual punishment are commonplace. All of these places lack the protection of basic human rights that make this country the land of the free.

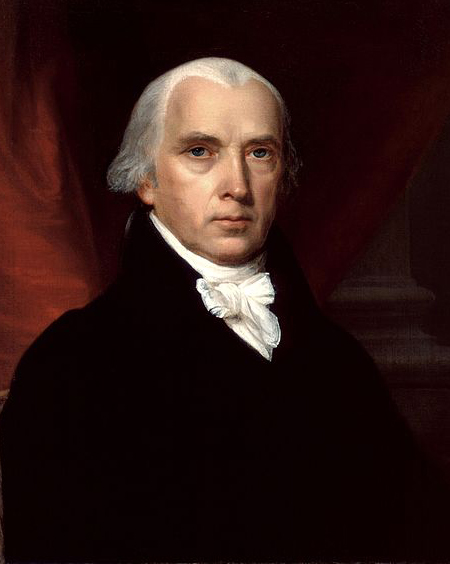

When our Constitution was first established, it was assumed that the description of specific powers granted to the government would leave no doubt as to what the government could and could not do, and that the absence of powers over the rights of the people would leave those rights protected. But Thomas Jefferson and others were wary of leaving such important matters up to inference. They insisted on a Bill of Rights that would state in unmistakable terms those rights of the people that must be left inviolate. In 1787, Jefferson wrote to James Madison: "A bill of rights is what the people are entitled to against every government on earth, general or particular; and what no just government should refuse, or rest on inferences." September 17, 1787, the delegates to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia signed the final draft of the Constitution and left to go back to their states. When Jefferson learned that the draft did not contain a Bill of Rights, he noted that it was reckless. He commented that if the states even considered ratifying it, it would amount to "a degeneracy in the principles of liberty." In 1787, he wrote to Madison: "A Bill of Rights is what the people are entitled to against every government, and what no just government should refuse, or rest on inference."

As it turned out, the Madison should have listened to Jefferson because many of the states would not ratify it without a Bill of Rights.

When the delegates at the Convention finished their work in Philadelphia, the only thing they created was a "proposal." That proposal for a Union, held together by the scheme of federal government outlined in Articles I - III, would have to go to all the states for ratification. Nine of the 13 states would have to ratify it for the Constitution to become effective for those ratifying states. But quickly, a fierce debate broke out in the states - between the Federalists (who were the majority at the Convention) and the Anti-Federalists (who were suspicious of the power delegated to the proposed federal government). The Federalists, of course, argued that the Constitution should be approved, but the Anti-Federalists urged the states not to ratify it. They were aggressive in their criticisms, and soon essays written by several of the anti-Federalists appeared in publications in the several states. They appeared under various assumed names, such as Brutus, Cato, Centinel, Aristocrotis, and the Federal Farmer. George Clinton, the Governor of New York, Richard Henry Lee and James Mason of Virginia, Samuel Adams, John Hancock, Elbridge Gerry, Nathaniel Ames, and James Winthrop of Massachusetts, and even Patrick Henry were anti-Federalists. Alexander Hamilton and John Jay of New York, and James Madison of Virginia, all representing key states that were siding with the anti-Federalists, got together to write a series of 85 essays that explained the Constitution in detail and addressed the criticisms outlined in the Anti-Federalist Papers. These would become known as The Federalist Papers.

For many states, the decision to support or oppose the new plan of government came down to one issue - whether their sovereign powers and the individual liberties of the People were jeopardized by its lack of a Bill of Rights. After all, they had rebelled against Britain because it had in their view ceased to respect their age-old liberties as Englishmen--liberties enshrined in the 1215 Magna Carta and the 1689 English Declaration of Rights. Having fought a long war to protect these rights, were they then to sacrifice them to their own government? Others countered that a bill of rights actually endangered their liberties... that listing the rights a government could not violate implied that unlisted rights could be restricted or abolished. After much discussion at the Philadelphia Convention, the majority of the delegates were of the latter opinion. But that decision cost the signatures of several high-profile delegates, such as George Mason and Edmund Randolph of Virginia and Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts. George Mason felt that the Constitution did not adequately provide protection for the states' rights and interests, Elbridge Gerry was not happy with the commerce power delegated to the federal government or with the taxing power which he felt might be burdensome on the states, and Randolph, a lawyer, was not content with the looseness of some of the language, fearing that future generations, and particularly the government itself, would seek sweeping changes to the meaning and intent of the document. [Edmund Randolph was the author of the Virginia Plan which was presented at the Constitutional Convention and George Mason was the author of Virginia's Bill of Rights].

Many of the state conventions ratified the Constitution, but called for amendments specifically protecting individual rights from abridgement by the federal government. The debate raged for months. By June of 1788, with assurances that a Bill of Rights would be proposed, nine states had ratified the Constitution, ensuring it would go into effect for those nine states. However, key states including Virginia and New York had not ratified and it wasn't sure that they would without an actual Bill of Rights. After all, the colonies had rebelled against Britain because it had in their view ceased to respect their age-old liberties as Englishmen - liberties enshrined in the Magna Carta ("Great Charter") of 1215 and the English Bill of Rights of 1689. Having fought a long and bitter war to protect these rights, were the states willing to sacrifice them to their own government?

In Virginia, Patrick Henry was accusing the proposed government of 'tending or squinting toward the monarchy' and being a 'national' rather than a 'federal' one, with no effective checks and balances against a majority or against a government determined to usurp power and no Bill of Rights to curb government power. He warned: "This proposal of altering our Federal Government is of a most alarming nature. You ought to be extremely cautious, watchful, jealous of your liberty, for instead of securing your rights you may lose them forever. If a wrong step be now made, the republic may be lost forever. If this new Government will not come up to the expectation of the people, and they should be disappointed - their liberty will be lost, and tyranny must and will arise. I repeat it again, and I beg Gentlemen to consider, that a wrong step made now will plunge us into misery, and our Republic will be lost." He continued: "Liberty, the greatest of all earthly blessings, gave us that precious jewel, and you may take everything else! ... The Confederation, this same despised government, merits, in my opinion, the highest encomium; it carried us through a long and dangerous war; it rendered us victorious in that bloody conflict with a powerful nation; it has secured us a territory greater than any European monarch possesses; and shall a government which has been thus strong and vigorous, be accused of imbecility, and abandoned for want of energy? Consider what you are about to do before you part with the government ... We are cautioned by the honorable gentleman who presides against faction and turbulence. I acknowledge also the new form of government may effectually prevent it; yet there is another thing it will as effectually do: it will oppress and ruin the people. ... This Constitution is said to have beautiful features, but when I come to examine these features, sir, they appear to me horribly frightful; among other deformities, it has an awful squinting-it squints towards monarchy; and does not this raise indignation in the breast of every true American? Your President may easily become king; your senate is so imperfectly constructed that your dearest rights may be sacrificed by what may be a small minority; and a very small minority may continue forever unchangeably this government, although horribly defective: where are your checks in this government?"

James Madison, the principal

author of the Constitution, knew that grave doubts would be cast on the Constitution if Virginia and New York (the home states of several of its chief architects, including Madison himself, and the authors of the Federalist Papers) did not adopt it. Perhaps he got that impression after Patrick Henry addressed the Virginia Ratification Convention on June 16, 1788 and spoke the following words:

Mr. Chairman, the necessity of a Bill of Rights appears to me to be greater in this government than ever it was in any government before. Let us consider the sentiments which have been entertained by the people of America on this subject. At the revolution, it must be admitted that it was their sense to set down those great rights which ought, in all countries, to be held inviolable and sacred. Virginia did so, we all remember. She made a compact to reserve, expressly, certain rights.

When fortified with full, adequate, and abundant representation, was she satisfied with that representation? No. She most cautiously and guardedly reserved and secured those invaluable, inestimable rights and privileges, which no people, inspired with the least glow of patriotic liberty, ever did, or ever can, abandon.

She is called upon now to abandon them and dissolve that compact which secured them to her. She is called upon to accede to another compact, which most infallibly supersedes and annihilates her present one. Will she do it? This is the question. If you intend to reserve your unalienable rights, you must have the most express stipulation; for, if implication be allowed, you are ousted of those rights. If the people do not think it necessary to reserve them, they will be supposed to be given up.

How were the congressional rights defined when the people of America united by a confederacy to defend their liberties and rights against the tyrannical attempts of Great Britain? The states were not then contented with implied reservation. No, Mr. Chairman. It was expressly declared in our Confederation that every right was retained by the states, respectively, which was not given up to the government of the United States. But there is no such thing here. You, therefore, by a natural and unavoidable implication, give up your rights to the general government.

Your own example furnishes an argument against it. If you give up these powers, without a Bill of Rights, you will exhibit the most absurd thing to mankind that ever the world saw - a government that has abandoned all its powers.... the powers of direct taxation, the sword, and the purse. You have disposed of them to Congress, without a Bill of Rights, without check, limitation, or control. And still you have checks and guards; still you keep barriers - pointed where? Pointed against your weakened, prostrated, enervated state government! You have a Bill of Rights to defend you against the state government, which is bereaved of all power, and yet you have none against Congress, though in full and exclusive possession of all power! You arm yourselves against the weak and defenseless, and expose yourselves naked to the armed and powerful. Is not this a conduct of unexampled absurdity? What barriers have you to oppose to this most strong, energetic government? To that government you have nothing to oppose. All your defense is given up. This is a real, actual defect. It must strike the mind of every gentleman.

When our government was first instituted in Virginia, we declared the common law of England to be in force. By this (federal) Constitution, some of the best barriers of human rights are thrown away. That system of law which has been admired and which has protected us and our ancestors, has been excluded. Is this not enough of a reason to have a Bill of Rights?

It was during this Ratification Convention in Virginia that Madison promised that a Bill of Rights would be drafted and submitted to the States. His promise reassured the convention delegates and the Constitution was approved in that state by the narrowest margin, 89-87. New York soon followed, but submitted proposed amendments. Two states, Rhode Island and North Carolina, refused to ratify without a Bill of Rights. North Carolina refused to ratify in July 1788, and Rhode Island rejected it by popular referendum in March 1788 and North Carolina refused to ratify it in their convention in July.

A year later, on June 8, 1789, referring to Virginia's Declaration of Rights and the recommendations of the several state ratifying conventions, Madison proposed a series of 20 amendments to the first Congress. He had kept his promise and did so with utmost urgency, for the First US Congress only convened three months earlier, on March 4 (and George Washington had only been inaugurated as the nation's first US President on April 31st). In the speech he gave to Congress to propose the amendments, he said:

"It appears to me that this house is bound by every motive of prudence, not to let the first session pass over without proposing to the state legislatures some things (amendments) to be incorporated into the Constitution, as will render it as acceptable to the whole people of the United States.... It will be a desirable thing to extinguish from the bosom of every member of the community any apprehensions that there are those among his countrymen who wish to deprive them of the liberty for which they valiantly fought and honorably bled.

In some instances the states assert those rights which are exercised by the people in forming and establishing a plan of government. In other instances, they specify those rights which are retained when particular powers are given up to be exercised by the legislature. In other instances, they specify positive rights, which may seem to result from the nature of the compact. Trial by jury cannot be considered as a natural right, but a right resulting from the social compact which regulates the action of the community, but is as essential to secure the liberty of the people as any one of the pre-existent rights of nature. In other instances they lay down dogmatic maxims with respect to the construction of the government; declaring, that the legislative, executive, and judicial branches shall be kept separate and distinct: Perhaps the best way of securing this in practice is to provide such checks, as will prevent the encroachment of the one upon the other.

But whatever may be form which the several states have adopted in making declarations in favor of particular rights, the great object in view is to limit and qualify the powers of government, by excepting out of the grant of power those cases in which the government ought not to act, or to act only in a particular mode. They point these exceptions sometimes against the abuse of the executive power, sometimes against the legislative, and, in some cases, against the community itself; or, in other words, against the majority in favor of the minority.

If they are incorporated into the constitution, independent tribunals of justice will consider themselves in a peculiar manner the guardians of those rights; they will be an impenetrable bulwark against every assumption of power in the legislative or executive; they will be naturally led to resist every encroachment upon rights expressly stipulated for in the constitution by the declaration of rights. Beside this security, there is a great probability that such a declaration in the federal system would be enforced; because the state legislatures will jealously and closely watch the operation of this government, and be able to resist with more effect every assumption of power than any other power on earth can do; and the greatest opponents to a federal government admit the state legislatures to be sure guardians of the people's liberty. I conclude from this view of the subject, that it will be proper in itself, and highly politic, for the tranquility of the public mind, and the stability of the government, that we should offer something, in the form I have proposed, to be incorporated in the system of government, as a declaration of the rights of the people.

I am convinced of the absolute necessity (of these amendments). I think we should obtain the confidence of our fellow citizens, in proportion as we fortify the rights of the people against the encroachments of the government."

In his speech, Madison emphasized the great concern of the states - How to prevent the encroachments of government? As he explained, the ten amendments to the Constitution - the Bill of Rights - were crafted to "limit and qualify the powers of government, by excepting out of the grant of power those cases in which the government ought not to act, or to act only in a particular mode." It was not individual freedom that the states wanted. After all, under the American system, all men were created with inalienable rights that come from our Creator and not government. No, our Founders and state leaders wanted freedom from government. The Bill of Rights doesn't grant rights. Rather, it recognizes rights. It requires that the government not interfere with those rights. In other words, our Founders and state leaders wanted constitutional liberty. "If they are incorporated into the Constitution, independent tribunals of justice will consider themselves in a peculiar manner the guardians of those rights; they will be an impenetrable bulwark against every assumption of power in the legislative or executive; they will be naturally led to resist every encroachment upon rights expressly stipulated for in the Constitution by the declaration of rights." It was a hopeful plan.

In fact is that the plan was not the brainchild of the Federalists, who won the day at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia. It wasn't the brainchild of James Madison, initially an avowed Nationalist. The Constitution was amended by the States because of the influence of the anti-Federalists. While it was the Federalists (in the true sense of their name) who rejected the Virginia Plan and supported state representation in the legislature (giving the government itself a "federal" nature), it wasn't enough for those who wanted more protection and security for the rights of the States and individuals.

[Note that our Founders, as early as the Constitutional Convention in 1787, came to appreciate state representation in government. They referred to it as providing a state 'negative' (a veto power) in government, in order to safeguard the rights, powers, and interests of the states. The same sentiment was emphasized in the state ratifying conventions, only in stronger language. For those who question the legitimacy of nullification, we can see its very origins in the states' representation in government. It is clear that the doctrine was part of the dialogue in our nation's very founding and was implicit in the very design of government].

It was Thomas Jefferson who impressed upon Madison the need for a Bill of Rights. He urged him to heed the concerns of the anti-Federalists, which now became the concern of the various states. The over-arching concern was the rise of national power at the expense of state power. For example, the Federal Farmer (authored most likely by Richard Henry Lee, of Virginia), in stressing the necessity of a Bill of Rights and protections against a consolidation of power in government, wrote: "Our object has been all along to reform our federal system and to strengthen our governments... However, the plan of government is evidently calculated totally to change, in time, our condition as a people. Instead of being thirteen republics under a federal head, it is clearly designed to make us one consolidated government." George Mason, a delegate to the Philadelphia Convention who refused to support the Constitution, explained that the plan was "totally subversive of every principle which has hitherto governed us. This power is calculated to annihilate totally the state governments." Brutus, another anti-Federalist, wrote: "The best government for America is a confederation of independent states for the conducting of certain general concerns, in which they have a common interest, leaving the management of their internal and local affairs to their separate governments. How far shall the powers of the states extend is the question."

Centinel, yet another Anti-Federalist, reminded readers of the nature of republics. Agreeing with Montesquieu (one of the philosophers our Founders relied heavily on), that a republic government could only survive in a small territory, the anti-Federalists came to the conclusion that America would have to be a federal republic and a union of states (and NOT the states united!). As small republics themselves, the states would provide the foundation for republican and limited government in our new Union. "From the nature of things, from the opinions of the greatest writers and from the peculiar circumstances of the United States, it is not practical to establish and maintain one government on the principles of freedom in so extensive a territory. The only plausible system by which so extensive a country can be governed consistent with freedom is a confederation of republics, possessing all the powers of internal government and united in the management of their general and foreign concerns...." [from Centinel]

Brutus agreed. "Neither the general government nor the state governments ought to be vested with all the powers to be exercised for promoting the ends of government. The powers are divided between them - certain ends are to be attained by the one and other certain ends by the other, and these, taken together, include all the ends of good government." [articulating our system of dual sovereignty].

Nathaniel Ames, of Massachusetts, wrote: "The state governments represent the wishes and feelings of the people. They are the safeguards and ornament of our liberties - they will afford a shelter against the abuse of power, and will be the natural avengers of our violated rights." Patrick Henry of Virginia agreed. He referred to the proposed government under the new Constitution a "consolidated and a dangerous" one, and added: "The States are the character and soul of a confederation. If the states be not the agents of this compact, it must be one great consolidated national government, of the people of all the states... The people sent delegates, but the states did."

Taken together, the anti-Federalists concluded that the United States could only exist successfully as a nation if "distinct republics connected under a federal head. In this case the respective state governments must be the principal guardians of the peoples' rights.... In them must rest the balance of government."

The US House debated and discussed the proposed amendments, and eventually edited, re-worked, and consolidated them down into 17 amendments. The Senate took up the amendments and made their own edits and alterations, and in September, the two houses got together and reached a compromise. Twelve amendments were approved on September 25 and then sent to the States for ratification. All in all, it has been said that only two major provisions among the proposed 19-20 original amendments were eliminated by the House and Senate.

The amendments were designed to protect the basic freedoms of US citizens from the reaches of government, namely the freedoms of speech, press, assembly, and exercise of religion, the right to bear arms for self protection, the right to be secure in one's person, home, and privacy against government searches and seizures, the right not to be denied Life, Liberty, or Property without due process, the right of habeas corpus, the right to fair criminal and civil legal proceedings and proper procedural safeguards, and the right to be spared cruel and unusual punishment. Additionally, one amendment (the 9th Amendment) was included to memorialize the notion that sovereign power originates in the individual and another (the 10th Amendment) was included to memorialize the federal nation of our government system ("the powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people").