REAL News for REAL People

Nullification: The Rightful Remedy to Curb Federal Tyranny - Part I

The Basis of Nullification: Federalism and Compact Theory --

Often we refer to our government as a "federal' government without really understanding what it means. To state that our government is a "national" government, on the other hand, would imply something completely different. A "federal" government implies that we are a federation of sovereign states which has granted or transferred some its authority to a government to serve, maintain, and support the union. A federal government implies a limited government that respects the sovereign powers of the states. It implies a government that "serves" the individual states. Indeed, we have a federal republic where the individual states come together and have joint deliberations in government, but those deliberation do not impair the sovereignty of each member.

We did not create a nationalistic entity - that is, a "national" government - which would imply that the sovereign powers of the states have been sacrificed to an all-powerful government. "Nationalism" was not on our Founders' minds, and for good reason. The delegates at the Constitutional Convention in 1787 nearly unanimously rejected that notion in favor of federalism. Nationalism is the unhealthy love of one's government, accompanied by the aggressive desire to build that governmental system to a point that it is above all else, and becomes the ultimate provider for the public good. Nationalism puts the nation before the Individual. We call our founding settlers and Founding Fathers "patriots" and not "nationalists." Patriotism is love of country, Nationalism is love of government.

"Federalism" is widely regarded as one of America's most valuable contributions to political science. It is the constitutional division of powers between the national and state governments - one which provides the most powerful of all checks and balances on the government of the people. It is the foundation upon which our individual rights remain most firmly secured.

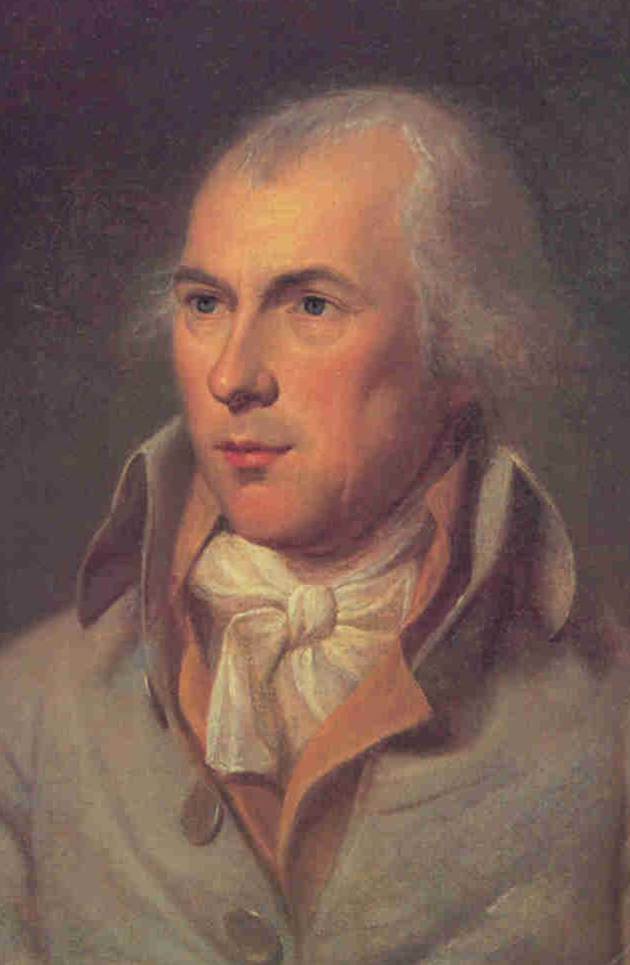

James Madison, "the Father of the Constitution," explained the constitutional division of powers this way in Federalist Papers No. 45: "The powers delegated to the federal government are few and defined. Those which are to remain in the state governments are numerous and indefinite. The former will be exercised principally on external objects, such as war, peace, negotiation, and foreign commerce..The powers reserved to the several states will extend to all the objects which, in the ordinary course of affairs, concern the lives, liberties, and properties of the people." Furthermore, Thomas Jefferson who declared the boundaries of government on the individual in the Declaration of Independence, emphasized that the states are not "subordinate" to the national government, but rather the two are "coordinate departments of one simple and integral whole. The one is the domestic, the other the foreign branch of the same government."

The principle of Federalism was incorporated into the Constitution through the Tenth Amendment, which states: "The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people." It is similar to an earlier provision of the Articles of Confederation which asserted: "Each state retains its sovereignty, freedom, and independence, and every power, jurisdiction, and right, which is not by this Confederation expressly delegated to the United States, in Congress assembled."

Our Founders had very good reason to draft the provisions in such terms and the states had very good reason to ratify the Tenth amendment on December 15, 1791. The issue of power - and especially the great potential for a power struggle between the federal and the state governments - was one that was very important at the time our Founding Fathers were trying to fashion an institution to serve the united purposes of the states. They deeply distrusted government power, and their goal was to prevent the growth of the type of government that the British has exercised over the colonies. They weren't willing to trade one tyrant government for another.

As history clearly records, adoption of the Constitution of 1787 was opposed by a number of our most important and well-known patriots - including Patrick Henry, Samuel Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and others. They passionately argued that the Constitution would eventually lead to a strong, centralized state power which would destroy the individual liberty of the People. These opponents would be termed the "Anti-Federalists," which is actually a misnomer of a name because they were the strongest supporters of the states' sovereign powers. [The Federalists were the group who won the day at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787]. It was because of the strength of their arguments, their persistence, their intellectual influence through many writings in widespread publications, and the very track record of history that led to the addition of the Tenth Amendment to the US Constitution.

As the Supreme Court acknowledged in 1931 in the case of United States v. Sprague: "The Tenth Amendment was intended to confirm the understanding of the people at the time the Constitution was adopted, that powers not granted to the United States were reserved to the States or to the people. It added nothing to the instrument as originally ratified."

It is exceedingly clear that the Tenth Amendment was written and adopted to emphasize the limited nature of the powers delegated to the federal government. In delegating just specific powers to the federal government, the states and the people, with some small exceptions, were free to continue exercising their sovereign powers.

Besides the principle of Federalism, another foundation upon which the doctrine of Nullification is based is the "Compact Theory of Federalism." This theory was explained and emphasized by Thomas Jefferson in the series of resolutions he wrote which would become the Kentucky Resolves of 1798. The compact theory states that our federal government was formed through an agreement by all of the states. That agreement (compact), our US Constitution, was ratified by all the original states and adopted by every additional state that entered the Union. The Constitution, as an agreement, and like all other agreements (or contracts), set out specific conditions, responsibilities, and limitations on the part of the parties. The parties to the compact were the states themselves and not the federal government. The federal government was merely a creation of the Constitution. Also, as with all contracts and agreements, the federal compact is limited by its language and by the intent when it was entered into. It is only legally enforceable under such conditions. In other words, the government is only legal for the specific purpose it was ratified for and under the precise terms (except for amendments properly adopted through the Article V amendment process). In other words, the Constitution is a contact between the individual states which they can break. And this was precisely what Thomas Jefferson referred to in his Declaration of Independence when he wrote the words:

"We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.--That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, --That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed."

To look at the frame of mind of the states when they adopted the Constitution, look at their comments in the ratifying conventions and look at the terms they used. The terms included "compact" and "agent" (meaning the federal government was intended to be an agent of the states). This is the best indicator of the foundations of our system of government. It is not for us to redefine those foundations. And it is certainly not for the federal government to do so. Again, it wasn't even a party to the compact; it was the creation.

South Carolina's Declaration of Causes of Secession ("Declaration of the Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union") adopted on December 24, 1860, provides a nice summary of the establishment of our country:

(With respect to the Declaration of Independence of 1776)... "Thus were established the two great principles asserted by the Colonies, namely: the right of a State to govern itself; and the right of a people to abolish a Government when it becomes destructive of the ends for which it was instituted. And concurrent with the establishment of these principles, was the fact, that each Colony became and was recognized by the mother Country a FREE, SOVEREIGN AND INDEPENDENT STATE.

In 1787, Deputies were appointed by the States to revise the Articles of Confederation, and on 17th September, 1787, these Deputies recommended for the adoption of the States, the Articles of Union, known as the Constitution of the United States.

The parties to whom this Constitution was submitted were the several sovereign States; they were to agree or disagree, and when nine of them agreed the compact was to take effect among those concurring; and the General Government, as the common agent, was then invested with their authority.

If only nine of the thirteen States had concurred, the other four would have remained as they then were-- separate, sovereign States, independent of any of the provisions of the Constitution. In fact, two of the States did not accede to the Constitution until long after it had gone into operation among the other eleven; and during that interval, they each exercised the functions of an independent nation.

By this Constitution, certain duties were imposed upon the several States, and the exercise of certain of their powers was restrained, which necessarily implied their continued existence as sovereign States. But to remove all doubt, an amendment was added, which declared that the powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States, respectively, or to the people. On May 23, 1788, South Carolina, by a Convention of her People, passed an Ordinance assenting to this Constitution, and afterwards altered her own Constitution, to conform herself to the obligations she had undertaken.

Thus was established, by compact between the States, a Government with definite objects and powers, limited to the express words of the grant. This limitation left the whole remaining mass of power subject to the clause reserving it to the States or to the people, and rendered unnecessary any specification of reserved rights.

We hold that the Government thus established is subject to the two great principles asserted in the Declaration of Independence; and we hold further, that the mode of its formation subjects it to a third fundamental principle, namely: the law of compact. We maintain that in every compact between two or more parties, the obligation is mutual; that the failure of one of the contracting parties to perform a material part of the agreement, entirely releases the obligation of the other; and that where no arbiter is provided, each party is remitted to his own judgment to determine the fact of failure, with all its consequences."

South Carolina's Declaration of Causes goes on to emphasize that stipulations in the Constitution were so material to the compact that without them, the compact itself would never have been made.

Can you imagine a reasonable person entering into an agreement of significant consequence without knowing how that document/agreement will be changed or interpreted in the future? No party would enter into such an agreement - especially with such enormous consequences as the States did in 1787.

Since Marbury v. Madison (1803), the Supreme Court has been seen as the final arbiter as to the meaning and interpretation of the Constitution. But why should the Court, or any federal court for that matter, be such a final arbiter? They are, after all, a branch of the federal government. How can such courts truly be expected to be a fair umpire for the States, especially when it was the States themselves, the parties to the compact (contract), which understood and meaning and intent of the Constitution and the purpose for the federal government. The foundational point upon which nullification rests is that the federal government cannot and must not be permitted to hold a monopoly on constitutional interpretation. If the federal government has the exclusive right to evaluate the extent of its own powers, it will continue to grow, regardless of elections, the separation of powers, and all the other limits and checks and balances built into our system of government. This is precisely what Thomas Jefferson and James Madison warned about when they crafted the Kentucky Resolves of 1798 and Virginia Resolves of 1798.

Sure, the Supreme Court has been historically seen as the ultimate and "infallible" judge of the constitutionality of the laws and actions of the federal government. But we can't forget that the Supreme Court is itself a branch of the federal government. In a dispute between the states and the federal government, is it reasonable to assume that the federal government can always come up with an unbiased resolution? (We've seen how resolutions have turned out over the years, as the states have been systematically stripped of their powers, rights, and obligations). Jefferson believed that under this arrangement, where the Supreme Court is the ultimate and "infallible" judge of the meaning of the constitution and the constitutionality of federal actions, the states would inevitably be eclipsed by the interests and ambitions of the federal government. As Judge Spencer Roane of Virginia (1762-1822) wrote: "It has, however, been supposed by some that the right of the State governments to protest against, or to resist encroachments on their authority is taken away, and transferred to the federal judiciary, whose power extends to all cases arising under the Constitution; that the Supreme Court is the umpire to decide between the States on the one side, and the United States (government) on the other, in all questions touching on the constitutionality of laws, or acts of the Executive. There are many cases which can never be brought before that tribunal, and I do humbly conceive that the States never could have committed an act of such egregious folly as to agree that their umpire should be altogether appointed and paid for by the other party."

Diane Rufino has her own blog For Love of God and Country. Come and visit her. She'd love your company.

| HB 1139: Greenbacks for Green Business | Editorials, Our Founding Principles, For Love of God and Country, Op-Ed & Politics | Friday Interview: N.C. Actual Innocence Commission Revisited |