Publisher's note: We believe the subject of history makes people (i.e., American people) smarter, so in our quest to educate others, we will provide excerpts from the North Carolina History Project, an online publication of the John Locke Foundation. This ninety-second installment, by Maximilian Longley, was originally posted in the North Carolina History Project.

On November 3, 1979, an armed confrontation between members of the Maoist Communist Workers Party (CWP) and several Klansmen and Nazis ended with four CWP members and one supporter being shot dead. Three trials soon followed, and CWP survivors and their supporters claimed that their anti-establishment views incited a conspiracy to have them killed.

Jerry Tung claimed that his father, Ernest Tung, a Chinese student at North Carolina State University, was murdered by the Ku Klux Klan in Raleigh in 1950. Historian William Wei believes Tung's claim and speculates that the alleged murder might have been a factor leading to the Greensboro confrontation. However, a State Bureau of Investigation (SBI) report, available in the NC State archives, expresses that the 1950 death of Tung's father was a suicide.

Tung founded a Maoist group called the Asian Study Group (ASG). The ASG later merged with other radical groups to form a new organization, also headed by Tung: Workers Viewpoint Organization (WVO). On the eve of the Greensboro shootings, the WVO changed its name to the Communist Workers Party (CWP). The CWP was one of several groups established as part of a Maoist revival within the radical community. To the Maoists, the pro-Soviet Communist Party USA was deemed soft on capitalism and lacking in militancy.

In 1979, the CWP "was consciously trying to upgrade its level of militancy, to become more adept at combining legal and illegal tactics" (according to CWP activist Signe Waller, whose husband was killed on November 3). This militant attitude was reflected in the actions of CWP members and supporters in New York City and in Greensboro. In New York's Chinatown, CWP members and supporters violently attacked the offices of a critical newspaper and members of a rival, radical organization opposing the political direction of a CWP front group. In Greensboro, CWP activists had violent confrontations with a rival Maoist group, the Revolutionary Communist Party. This confrontational attitude reflected the tenets of Maoist communism: faithful communists are beset by enemies, including capitalist sympathizers within the communist movement.

CWP activists in Greensboro also sought to organize textile workers, and to displace other union activists who were seeking to accomplish the same objective. Dr. James Waller, a physician who belonged to the CWP, got a job in a textile plant and organized the workers. Dr. Waller was later fired, after being accused of concealing his professional status.

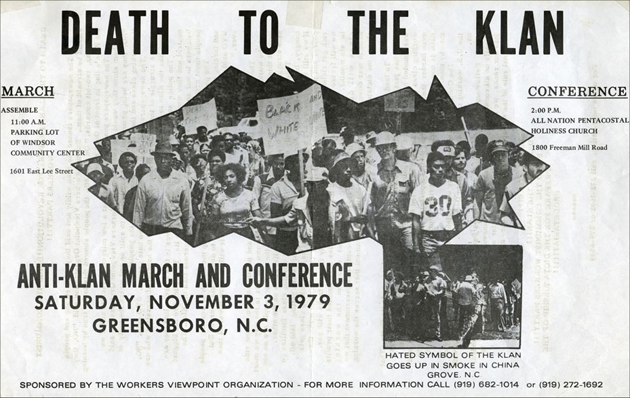

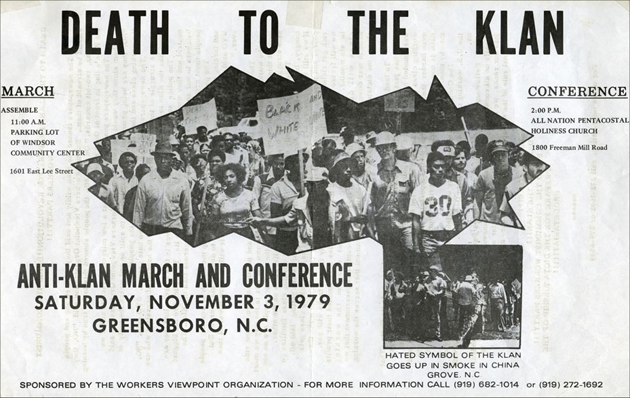

Greensboro rally poster in 1979: Above. Click to enlarge.

Greensboro rally poster in 1979: Above. Click to enlarge.

The CWP sought to wage a campaign against the local Ku Klux Klan, attempting to disrupt a Klan showing of the movie Birth of a Nation at the public library in the town of China Grove. The CWP members believed local anti-Klan activists lacked sufficient militancy in confronting the Klan.

Planning a "Death to the Klan" rally near the Morningside Heights housing project in Greensboro on November 3, 1979, the CWP publicly challenged the Klan. CWP said that cowardly Klan members would not make an appearance and face the "wrath of the people." The local Klan, however, sought the assistance of some neo-Nazis and responded to CWP's challenge.

There were two government informers in the ranks of the Klan and Nazis. Edward Dawson, who had formerly been an informant in the Klan on behalf of the Federal Bureau of Investigations, was now informing on the group for the Greensboro Police Department (GPD). Dawson's allegiance was not clear - depending on one's interpretation, he was either a stooge of the GPD or a manipulator trying to work both sides. Dawson got a copy of the CWP's planned parade route from the GPD.

Klansmen and Nazis (including Dawson) drove their cars to the site of the CWP rally. GPD officers were not present at the scene. Details of the ensuing confrontation between the CWP and the Klansmen/Nazis have been somewhat controversial. It appears that Bernard Butkovich, an agent of the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (ATF), was doing undercover work among the Nazis.

Five people were killed, four of whom were CWP members. The CWP dead were Cesar Cauce, William ("Bill") Sampson, Sandra ("Sandi") Smith and Dr. James Waller. The fifth fatality was Dr. Michael Nathan, a physician who had worked with the CWP activists and who was married to CWP member Martha ("Marty") Nathan. There were no fatalities on the Klan/Nazi side.

The CWP held an armed funeral March in Greensboro, where Tung praised the "martyrs" and hailed the coming revolution. CWP members said that the shootings were part of a government plot, and they sought to "serve notice" on the purported plotters by (among other things) seeking to disrupt the national Democratic Party convention.

The Klansmen and Nazis accused of involvement in the shootings were subject to three trials. First was a state criminal trial on murder charges, where the defendants were acquitted. This was followed by a federal criminal trial on charges of violating the civil rights of the CWP members who had been shot - again, the defendants were acquitted. Finally, there was a federal civil trial, based on a lawsuit filed by the CWP survivors against the alleged shooters and against government authorities alleged to have culpably failed to prevent the shootings. In this third trial, the jury found the Klan/Nazi shooters civilly liable for the death of Dr. Michael Nathan, the only non-CWP victim. The jury also blamed the Greensboro Police Department for failing to do more to prevent the shootings.

Twenty years after the various trials were over, the CWP survivors - who had gone into other lines of work as the CWP dissolved - pressed for another investigation of the 1979 shootings. A private group sympathetic to the survivors - named the Greensboro Truth and Reconciliation Commission - held public hearings and conducted research into the shootings. Although noting some of CWP's radical views, the final report of the Greensboro Truth and Reconciliation Commission blamed mostly the "absence of police" and the Greensboro establishment's resistance to necessary social change as the main causes of the shootings.

Reverand Nelson Johnson - a CWP survivor of the shootings and longtime Greensboro activist - has subsequently accused the Greensboro Police Department of destroying documents relating to the 1979 shootings.

Sources:

Archives of the Greensboro Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Carnegie Negro Library, Bennett College, Greensboro, NC.

Bermanzohn, Paul, The True Story of the Greensboro Massacre. Cesar Cauce Publishers, 1981.

Bermanzohn, Sally, Through Survivors' Eyes: From the Sixties to the Greensboro Massacre. Vanderbilt University Press, 2003.

Elbaum, Max, Revolution in the Air: Sixties Radicals turn to Lenin, Mao and Che, Verso, 2002.

Faith Community Church, "Media Announcement: Pastors to Disclose Details on the Destruction of Approximately 50 Boxes of Greensboro Police Files Related to the November 3, 1979 Klan-Nazi Killings During Former Police Chief David Wray's administration," Press Release, February 25, 2008.

Greensboro Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Final Report, 2006, available on GTRC Web site, http://www.greensborotrc.org/.

Ho, Fred (ed.), Legacy to Liberation: Politics and Culture of Revolutionary Asian/Pacific America, AK Press, 2000.

Kwong, Peter and Dusanka Miscevic, Chinese America: The Untold Story of America's Oldest New Community. New Press, 2007.

"Lawbreakers: The Greensboro Massacre" The History Channel. Lawbreakers Series. Video Cassette. 46 minutes. Color. 2000. Broadcast October 13, 2004.

Longley, Maximilian, "1979 Klan-CWP Clash Revisited in Greensboro," Metro Magazine, February 2006, available online at http://www.metronc.com/article/?id=1021.

Longley, Maximilian, "Greensboro Shooting Report Prompts Diverse Reactions," Carolina Journal, July 2006, pp. 1, 2, 5; available online at http://www.johnlocke.org/acrobat/cjPrintEdition/cj-july2006-web.pdf.

State Bureau of Investigation report on the death of Ernest Tung (forwarded to V. K. Wellington Koo, Chinese (Taiwanese) Ambassador to the United States), Governor Kerr Scott papers, Box 95 (1951), "SBI" folder, North Carolina State Archives.

Tani, Karen, "Asian Americans for Equality and the Community Based Development Movement: From Grass Roots to Institutions," undergraduate honors thesis, Dartmouth College, 2002.

Tung, Jerry, The Socialist Road: Character of Revolution in the U.S. and Problems of Socialism in the Soviet Union and China, Cesar Cauce Publishers, 1981.

Waller, Signe, Love and Revolution: A Political Memoir, Rowman and Littlefield, 2002.

Wei, William, The Asian American Movement, Temple University Press, 1994.

Wheaton, Elizabeth, Codename Greenkil: The 1979 Greensboro Killings, University of Georgia Press, 1987.

Zucker, Adam, "Closer to the Truth," documentary, 2007.

Greensboro rally poster in 1979: Above. Click to enlarge.

Greensboro rally poster in 1979: Above. Click to enlarge.