Publisher's Note: These posts, by Dr. Terry Stoops, and aptly titled CommonTerry, appears courtesy of our friends at the John Locke Foundation. A full account of Dr. Stoops's posts, or him mentioned as a credible source, are listed here in BCN.

Are U.S. students good problem solvers?

Earlier this week, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) released a new report, "PISA 2012 Results: Creative Problem Solving: Students' Skills in Tackling Real-Life Problems."

How did students from the United States fare? Meh.

In 2012, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) assessed the problem solving skills of a representative sample of 85,000 15-year-olds worldwide, including 1,273 from the United States.

According to OECD researchers, the PISA problem-solving test focused on "general reasoning skills, their ability to regulate problem-solving processes, and their willingness to do so, by confronting students with problems that do not require expert knowledge to solve." They note that students' ability to think through "real-life" problems is a skill that is one of the keys to building a successful 21st century workforce. But I would take it one step further and say that problem solving is also essential to cultivating a thoughtful and judicious citizenry.

So, how did test-takers from the United States fare?

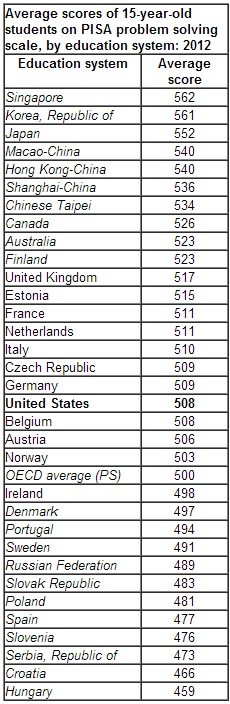

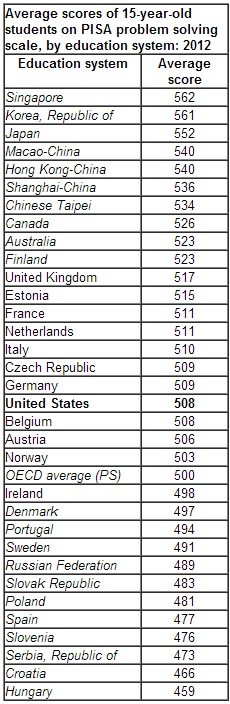

While the U.S. average (508) was significantly higher than the international average score (500), ten education systems had average scores that were significantly higher than the United States (See Facts and Stats below). Some, but not all, are located in the Pacific Rim. Canada, Australia, and Finland significantly outperformed the United States and most other nations, for that matter, on the PISA problem-solving test.

Education systems with the best problem solvers are also those that typically boast the highest scores on international tests of mathematics, science, and reading literacy. In other words, we can assume that superior problem solvers possess a strong foundation in "the basics." Furthermore, rote memorization and direct instruction, as practiced by a number of the top performing systems, does not appear to impede students' ability to solve "real world" problems.

OECD disaggregates PISA test scores in several ways. One of the most interesting is the breakdown of average score by the PISA index of economic, social and cultural status (ESCS), which is something akin to what we call socioeconomic status. In general, the ranking of students in the bottom quarter of the ESCS index mirrors the overall results on the problem-solving test.

That is not to say that education systems do not have large gaps between poor and rich students, i.e., children in the bottom quarter and those in the top quarter of the ESCS index. South Korean children at the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder had the highest average score among participating systems, but the gap between their average scores in the bottom and top quartile was still about 54 points. The United States had a gap of 76 points. But that tells only part of the story.

According to the test results, the average underprivileged student in South Korea, Macao-China, Japan, and Singapore was a better problem solver than the average poor, working, and middle class test-taker in the United States. Admittedly, there are some technical problems with such a comparison, but I think it is a finding that should be the subject of additional inquiry and debate.

In fact, data alone cannot determine why one education system outperforms another. The characteristics of the top performing nations vary, with one exception. On average, they spend less money per student than the United States. While there is no apparent relationship between funding and performance, resources do matter. That is why any discussion of education funding should focus on how education systems use their resources to raise student achievement, i.e., educational productivity.

In the long run, however, I doubt that the latest PISA test results will encourage stakeholders to engage in serious discussions of educational productivity. And that is why the United States will continue to occupy "the crowded middle" on international assessments of student performance.

Facts and Stats

Note:

Note: Italicized education systems had average scores that were higher and lower (in terms of statistical significance) than the United States.

Acronym of the Week

PISA -- Program for International Student Assessment

Quote of the Week

"Although indicators can highlight important issues, they do not provide direct answers to policy questions. To respond to this, PISA also developed a policy-oriented analysis plan that uses the indicators as a basis for policy discussion."

-

OECD,

"PISA 2012 Results: Creative Problem Solving: Students' Skills in Tackling Real-Life Problems," April 2014.

Click here for the Education Update archive.