Committed to the First Amendment and OUR Freedom of Speech since 2008

The Government Shall Not Prohibit the Free Exercise of Religion

One only need look at the Court's decision in McCulloch v. Maryland (1819) to see the implications of having the federal government resolving disputes over what the meaning of the Constitution should be. We were only on our third President and the Court was already making its own independent determinations as to how much power should be concentrated in the newly-created federal government. The McCulloch case centered around the meaning of the "Necessary and Proper" clause of the Constitution and looked to two Founders for the authoritative interpretation of its proper scope - Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton. Thomas Jefferson believed in a limited federal government with strong individual state governments. He was a strict constructionist who believed that every word of the Constitution makes a vital determination of power versus liberty. He said: "On every question of construction let us carry ourselves back to the time when the Constitution was adopted, recollect the spirit manifested in the debates, and instead of trying what meaning can be squeezed out of the text or invented against it, conform to the probable one which was passed." Alexander Hamilton, on the other hand, believed in a strong central government. In fact, when he attended the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787, he proposed a government modeled after the British monarchy, with a president appointed for life. Although he eventually embraced the Constitution adopted by his fellow delegates, and he gave proper assurances as to the true intention of the document in the Federalist Papers, he continued to believe that Congress should have more legislative powers than those expressly stated in Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution.

The facts of the case are as follows: After an initial failed attempt to establish a National Bank 1791, Congress finally established one in 1816. Many states opposed branches of the National Bank within their borders. They did not want the National Bank competing with their own banks. The state of Maryland imposed a tax on the bank of $15,000/year, which cashier James McCulloch of the Baltimore branch refused to pay. The case went to the Supreme Court. Maryland argued that as a sovereign state, it had the power to tax any business within its borders. Furthermore, it objected to the establishment of a National Bank in the first place as an unconstitutional exercise of Congress's power. Maryland argued: "The powers of the General Government are delegated by the States, who alone are truly sovereign, and must be exercised in subordination to the States, who alone possess supreme dominion." The government, in response, argued that the people have, in express terms, decided that

"this Constitution, and the laws of the United States, which shall be made in pursuance thereof, shall be the supreme law of the land." (US Supremacy Clause, Article VI). It further argued that since the federal government was entrusted with ample powers on which the country depends, there must be ample means for their execution, and a national bank was "necessary and proper" for Congress to establish in order to carry out its enumerated powers, such as raising revenue, paying debts, etc. The question before the Court, then, ("the subject of fair inquiry") was 'How far such means may be employed?' In other words, what is the proper scope of the Necessary and Proper Clause.

Article I, Section 8, clause 18 reads: "To make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers, and all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof."

Note that Jefferson nor the State of Maryland were challenging the supremacy of the Constitution. The status of supremacy was addressed in Federalist #33 (written by Hamilton) and Federalist #44 (written by Madison)] and was settled with the ratification by the States. The issue was the interpretation of the Constitution and the proper scope of powers. How broad would the Necessary and Proper powers be construed?

The Supreme Court centered its analysis on the view of Jefferson and Hamilton, in part because they were both involved in the debate surrounding a National Bank before Congress in 1791. According to Jefferson, the establishment of a National Bank exceeded Congress' authority under the Constitution. With respect to the Necessary and Proper clause, he argued that the Bank was not necessary, and that Congress could certainly meet its constitutional responsibilities without one. He defended the interpretation of the Constitution by arguing that "necessary and proper" meant exactly that. "Necessary" meant 'necessary' and not merely 'convenient.' Sure, the Bank might be convenient, he noted. But the Constitution allows only for those means which are "necessary" and not for those which are merely 'convenient.' Jefferson further argued that the delegates to the Constitutional Convention specifically rejected the power to erect a bank because it would have caused the Constitution to be rejected by the States. In 1800, James Madison wrote that Jefferson's interpretation of the clause is "precisely the construction which prevailed during the discussions and ratifications of the Constitution," and "it cannot too often be repeated that this limited interpretation is absolutely necessary in order for the clause to be compatible with the character of the federal government, which is possessed of particular and defined powers only, rather than general and indefinite powers."

Hamilton countered with a lesson on the meaning of the word "necessary," just as Bill Clinton gave America a lesson on the meaning of the word "is." [See fearistyranny.wordpress.com. Contending that his statement at his grand jury hearing that "there's nothing going on between us" had been truthful because he had no ongoing relationship with Lewinsky at the time he was questioned, Clinton said, "It depends upon what the meaning of the word 'is' is]. Hamilton explained that "necessary often means no more than needful, requisite, incidental, useful, or conductive to." Contracts often include a term that provides some power to accomplish the goals of the agreement (a 'necessary and proper' clause, if you will), but Hamilton's view was more that the Constitution is not an firm legal document but more of a "rubber" instrument, open to broad interpretations. In other words, it could be broad enough to be interpreted as Congress sees fit. Hamilton might just have been the father of the "living document" view of the Constitution.

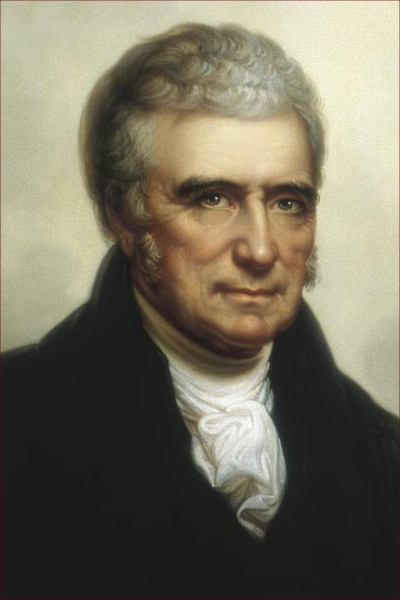

Jefferson was highly critical of the Marbury decision as violating states' interests and destroying the balance of power between the states and federal government and by 1819 was growing ever more leery of

Chief Justice John Marshall

Chief Justice John Marshall wrote, "Although, among the enumerated powers of government, we do not find the word 'bank,'...we find the great powers to lay and collect taxes; to borrow money; to regulate commerce... We conclude that --

1). The clause is placed among the powers of Congress, not among the limitations on those powers.

2). Its terms purport to enlarge, not to diminish, the powers vested in the Government. It purports to be an additional power, not a restriction on those already granted. No reason has been or can be assigned for thus concealing an intention to narrow the discretion of the National Legislature under words which purport to enlarge it. The framers of the Constitution wished its adoption, and well knew that it would be endangered by its strength, not by its weakness. Had the intention been to make this clause restrictive, it would unquestionably have been so in form, as well as in effect. (ie, the framers would have included the word "expressly limited to...")

We admit, as all must admit, that the powers of the Government are limited, and that its limits are not to be transcended. But we think the sound construction of the Constitution must allow to the national legislature that discretion with respect to the means by which the powers it confers are to be carried into execution which will enable that body to perform the high duties assigned to it in the manner most beneficial to the people. Let the end be legitimate, let it be within the scope of the Constitution, and all means which are appropriate, which are plainly adapted to that end, which are not prohibited, but consist with the letter and spirit of the Constitution, are Constitutional."

Marshall also noted an important difference between the Constitution and the Articles of Confederation. He wrote that the Articles stated that the states retained all powers not "expressly" given to the federal government. The Tenth Amendment, on the other hand, did not include the word "expressly." He argued that this was further evidence that the Constitution did not limit Congress to doing only those things specifically listed in Article I.

And finally, the Court ruled that Maryland could not tax the national bank: "That the power to tax involves the power to destroy; that the power to destroy may defeat and render useless the power to create; that there is a plain repugnance in conferring on one Government a power to control the constitutional measures of another, which other, with respect to those very measures, is declared to be supreme over that which exerts the control, are propositions not to be denied. But all inconsistencies are to be reconciled by the magic of the word CONFIDENCE. Taxation, it is said, does not necessarily and unavoidably destroy. To carry it to the excess of destruction would be an abuse, to presume which would banish that confidence which is essential to all Government."

Notice three things with this decision:

(1) The Court clearly failed to read the Federalist Papers and the transcripts of the State ratifying conventions, all declaring that the government would be limited in scope.

(2) The power of a state to tax an entity of the federal government would be the "power to destroy," as the Court noted. Yet the Court has no problem with the excess taxation of individuals. Excess federal taxation of individuals reduces the amount of taxation the state can morally levy on its inhabitants and therefore the state suffers at the expense of an excessively-funded federal government.

(3). Hamilton's views of a "flexible" Constitution were given improper weight, in relation to the overwhelming documentation to the opposing view, and by far more credible Founders than Hamilton. Again, Hamilton showed up to the Constitutional Convention to propose and promote the monarchist view of government. Americans just won their independence from a tyrant King George and Hamilton was pushing the very same system for America. He was the strongest advocate of a strong central government and the least committed to the cause of states' rights. When he was unanimously and soundly rejected in Philadelphia, he stomped out of Independence Hall and went back to New York to pout. When the Constitution was written, although he had withdrawn from the Convention, Hamilton returned to sign it. He also noted that "he seemed to be very much out of step with the rest of the Constitution's drafters." When it seemed possible that two of the most powerful states in the Union - New York and Virginia - would not ratify the Constitution because it appeared to take too much power from the States, Hamilton stepped it up and wrote at least half of the Federalist Papers to explain the interpretation and scope of each section of the Constitution and to give assurances to those states still having reservations. So, knowing that the States were looking for the bona fide interpretation of the Constitution and were looking for assurances on which to ratify and assent to it, the Supreme Court decided to look past the spirit of the Federalist Papers and gave weight to Hamilton's "personal" view that the Constitution should be read broadly. This would be the approach that the Court would take all too often in our history.

Ironically, even Hamilton insisted, in Federalist #78, that unless the people had solemnly and formally ratified a change in the meaning of the Constitution, the courts could not proceed on any other basis.

We saw the same type of misplaced emphasis and incorrect interpretation by the Supreme Court when it interpreted the Commerce Clause under FDR's administration. We also saw how the Supreme Court applied the 14th Amendment, to the destruction of States' rights, in disregard to the intent of that amendment. Religious rights have been eroded in a series of decisions stemming from this poisoned interpretation. And no doubt, marriage rights will be eroded in this way as well. An analysis of Supreme Court decisions from the founding of our country to the present will unfortunately show the American people that the Supreme Court very rarely referenced the Federalist Papers up until about 1930. By "very rarely," I mean they were referenced about 4-5 times total in a 10-year period. The frequency increased in the 1960's when the Court began to reference the Papers about 2 times each year. When William Rehnquist joined the Supreme Court as Chief Justice in 1968, there was a significant increase in the use of the Federalist Papers in deciding cases touching on the Constitution.

So, we see the slow but constant erosion of the Constitution's protection of liberty by the erosion of its fundamental and critical elements of check and balance. First, the Supreme Court elevated its power early on, in disregard to the assurances given by our Founders in Federalist #78 and Federalist #81, and then it almost completely destroyed the balance of power between the States and federal government with the 14th Amendment. From the very beginning, with Jefferson's term as President, the Court and the other branches systematically concentrated power in the federal government and did so with a willing and an intentional blind eye to the assurances and warnings provided by our Founders (in disregard to their oaths).

The federal government cannot be permitted to hold a monopoly on the interpretation of the Constitution and on what it believes is best for the American people, when everything our Founders stood for and promoted was the notion that people must be protected from their government. If the Supreme Court should end up upholding Obamacare (Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act) when it finally hears the case in mid-2012, then we know that the US Constitution is dead. We will know it is meaningless in constraining the government with respect to the People. And that would be the point at which Americans would need to embrace the words of the Declaration of Independence which reads: "That whenever any form of government becomes destructive to these ends, it is the right of the people to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness."

That being said, and that point hopefully having been made, we need to be concerned with the government's growing hostility to religion and its ever-growing disengagement with the American people and its independent agenda. Judging by the trend in our nation's history of government concentrating its power and making decisions it believes are "in the best interests of the county," and the Supreme Court steadily stripping our rights, we should absolutely be concerned at the future of our freedom to exercise our religion freely. We are heading in a selfish direction, where individual pursuits trump general moral guidelines for strong individual and family foundations. We are heading in a direction where it is "cool" and acceptable to bash Christians. One look no further at the vile tweet that hate mongerer Bill Maher sent a few days ago attacking Tim Tebow for his public displays of faith (ie, his prayers before each game). Amoral lifestyles and hate groups are tearing down traditional institutions that have been place to promote stability and real human value in society. Christian religious groups are being harassed; schools are no longer the beacon of learning that they once were; and marriage is being attacked. For example, there are efforts to undermine the traditional status of "marriage." Even President Obama announced that the government would not enforce DOMA (the federal Defense of Marriage Act). The executive branch is supposed to enforce the laws of the land. Challengers of traditional marriage want to remove the religious ties to marriage so that homosexual couples can enjoy the same status as heterosexual couples without feeling any 'stigma." But we all know that there are strong religious overtones and implications in marriage, which there should be. Without such, marriage would be treated merely as a contract, and the bonds of marriage are so much more sacred and important than that. The bedrock foundation of a strong moral society is a stable family unit with properly-defined roles and responsibilities.

We are becoming a nation of conflict and of hate because we've allowed religion to be taken out of public life and out of our schools. When we go God's way, we will necessarily bump into the Devil. So we have to be strong. We're already taking on the government so maybe taking on the Devil won't seem so bad in relation. At times, they seem to be one and the same anyway.

Let's continue to realize how important the Christian faith is to the integrity of this country and keep the pressure on and reflect and pray and find out how we can best advocate for our religious principles and at the same time for the principles that underlie and expand our liberty. A stand for religious principles is a stand for liberty.

I have been called many names for speaking out for the importance of religion and for the rightful recognition of Christianity in America. The names don't bother me. Rather, I'm honored to speak up when I can. I'm honored to reflect upon the contributions of our religious forefathers, which are too numerous to mention. I'm honored to speak for those who keep the faith and who show goodness and virtue in word and deed and set a living example by the lives they lead. It's these people who give hope to many that our country may not be doomed to darkness. I'm always reminded of why it's important to speak out against our government when they are violating our rights when I remember a quote I read at the Holocaust Museum in Washington DC. It was written by Pastor Martin Niemoller, who would not go along with the Nazis and was sent to Dachau concentration camp. Pastor Niemoller wrote:

First they came for the Socialists, and I did not speak out -- because I was not a Socialist.

Then they came for the Trade Unionists, and I did not speak out -- because I was not a Trade Unionist.

Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out -- because I was not a Jew.

Then they came for me -- and there was no one left to speak for me.

References:

Details of Everson v. Board of Education ("Wall of Separation") case and discussion of Federalist Papers #78-81 - See Diane Rufino, "THE JUDICIARY: The Supreme Court Judicial Activism," July 2011. Referenced at: http://knowyourconstitution.wordpress.com/2011/07/23/the-judiciary-the-supreme-court-judicial-activism/

Thomas E. Woods Jr., Nullification, 2010, Regnery Publishing.

Rideronthet (blog name), "Jefferson v. Hamilton, Federal Powers, and the Marshall Court, March 9, 2009. Referenced at: http://fearistyranny.wordpress.com/2009/03/09/jefferson-v-hamilton-federal-powers-and-the-marshall-court/

Bill of Rights Institute, McCulloch v. Maryland (1819). Referenced at: http://www.billofrightsinstitute.org/page.aspx?pid=694

McCulloch v. Maryland, 17 U.S. 316 (1819). Referenced at: http://www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/historics/USSC_CR_0017_0316_ZS.html

Citations to the Federalist Papers by Supreme Court - Professor Daniel Coenen, "Fifteen Curious Facts About the Federalist Papers," University of Georgia School of Law, April 1, 2007. Referenced at: http://digitalcommons.law.uga.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1001&context=fac_pm

Diane Rufino has her own blog For Love of God and Country. Come and visit her. She'd love your company.

| How are the Feds using private information on your children? | Editorials, For Love of God and Country, Op-Ed & Politics | American justice: Eric Holder style |