Boldly Committed to Truth Telling in the False Face of Fakery

Self-Governing Individuals Are Necessary for a Self-Governing Society

Self-governing individuals are necessary to have a self-governing society. That is, only a moral and disciplined people are capable of being governed by a limited government. Those who are not need greater government. The Pilgrims taught us this when they established the successful colony in Plymouth.

The term "self-governing" refers to the ability of individuals to exercise control over oneself. It is the internal obligation one feels to do the right thing. It is the willingness of individuals to consciously choose and hold onto productive principles that apply in diverse situations. Self-government means self-reliance, self-discipline, and self-improvement. As Thomas Paine said, self-governing individuals are necessary to have a self-governing society. Representative democracy ultimately depends on the moral character of the people and of the representatives elected. As James Madison, chief architect of the Constitution, wrote: "To suppose that any form of government will secure liberty or happiness without any virtue in the people, is a chimerical idea."

Self-governing individuals are necessary in order that the United States can hope to maintain a government of constitutional limits and of a size and scope that can be accountable to the people.

The debate at the core of the growing socialist nature of our government is how much should government do to help those who are less fortunate than others? An entire political party and an entire social movement has been created to answer that question: Total redistribution and equality of status. They are devoted to redefining what the United States stands for, the nature of government, and the new rights that individuals are entitled to and those that government can now regulate in the name of social justice. They are devoted to the tearing down of the fundamental institutions on which successful self-government is based, such as the family, church, and an education system that educates and not indoctrinates. They are devoted a tireless agenda of trying to "do good without God."

But good government depends on the character and virtue of the people it represents.

Character is built by overcoming obstacles. People can and do raise themselves out of poverty. The success stories of millions of immigrants paint a picture of the long-run rewards of discipline, perseverance, and sacrifice. If those stories are to continue, we must protect our liberties, accept our responsibilities, and practice virtue. We must never lose sight of the primary functions of government, as laid out in our Declaration of Independence; otherwise, we have a government in charge of defining its functions rather than We the People defining our government. If we wish to hold on to the grand notion, established for this nation by our Founders, that sovereign power to govern rests first and foremost with the People, then we honor our founding principles. According to the Declaration, protecting persons and protecting property are the two main functions of good government. When government steps beyond those legitimate functions, it steps outside the bounds of justice. As James Madison wrote: "That is not a just government, nor is property secure under it, where the property which a man has in his personal safety and personal liberty, is violated by arbitrary seizures of one class of citizens for the service of the rest."

But the more fundamental debate that is going on in this country is the one which speaks directly to the character of each individual. And that debate is ultimately the one over religion and its proper role in our society.

Character is defined by the set of moral qualities that a person possesses or one's moral strength. Character is the inner strength to do what is right even when no one is looking.

There is a deeply-embedded understanding in this country, stemming from our very founding settlers, patriots, and Founding Fathers, that religion and morality are fundamentally linked. Morality has roots in religious doctrine. In the Old Testament, God handed down a series of commandments to guide man's conduct. Man is free indeed, but even the Bible teaches that he should not be free to do everything he pleases. And so we have the Ten Commandments (on which common law, including criminal law, has been based). In the New Testament, God has established a new covenant with all who believe. And so we see a strong them of forgiveness, compassion, selflessness, and love in those books. Jesus himself summed up his Father's commandments in two great commandments: the command to love God with all one's heart and mind (see Deuteronomy 6:5), and the command to love the neighbor as the self (see Leviticus 19:18). Morality sees its roots therefore in the desire to always do good and do what is right. Religion provides the motivation and the reason to do good. It provides meaning to live a moral life. Thomas Paine believed that the moral duty of man consists in imitating the moral and beneficence of God.

There are moral limits to human behavior that are intertwined into our very nature. They not simply accidents or norms born out of history. There are permanent standards of what is right and wrong, and what is natural and what is unnatural. We regard such limits as something that must be conserved to protect character from avarice, envy, unhealthy ambition, entitlement, a sense of superior self-worth, and destruction. As Russell Kirk noted in his book, The Conservative Mind, we have a "belief in a transcendent order, or body of natural law, which rules society as well as conscience."

Our Founding Fathers saw morality as dependent on religious principles rather than on some internal value system because they believed that morality is based on timeless truths. Despite the various religious beliefs of our Founders, they shared a strong common belief that moral truths exist and are necessary for people to responsibly self-govern their own affairs. And that's why we see the historical record full of advice from them to remain a moral and religious people.

Lasting virtue is never forced; it is not passed in our genes. It is born out of a respect for certain fundamental and eternal truths based on right versus wrong, good versus bad, fair versus unfair. It is born out of love and deep respect for one's fellow man and for the rights that he values for everyone.

And so we see that the debate has intensified over whether religion is critical to self-government. I would argue that there is no element more important to one's individual behavior than the influence of religion and the power of the conscience. And that's why I believe that our Founders intended for the government to encourage the full expression of religious rights and not try to prevent it (using its arbitrary "Wall of Separation" to chill that expression).

Unfortunately, all too often we hear that government and schools aren't supposed to legislate or teach morality. But if we look at the roots of government and the purpose of law, we find out that the exact opposite is true.

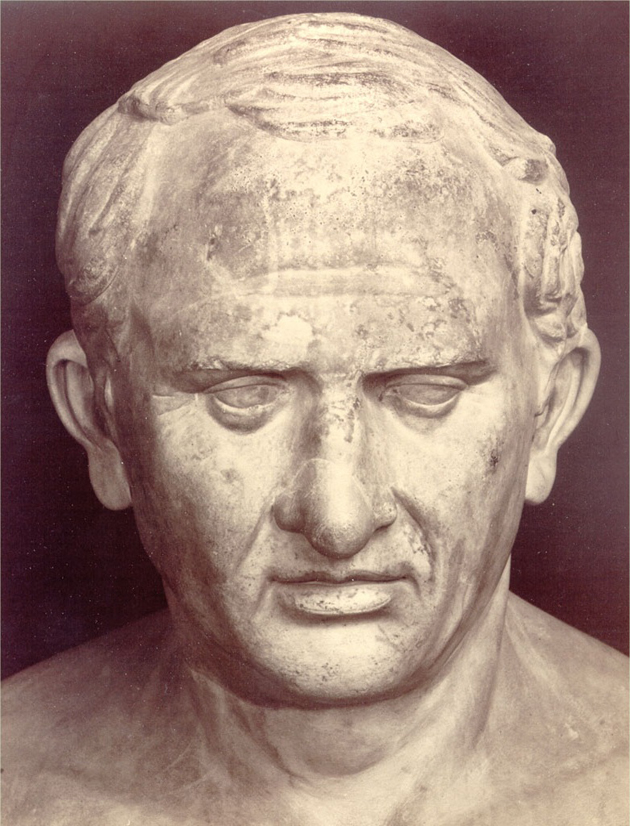

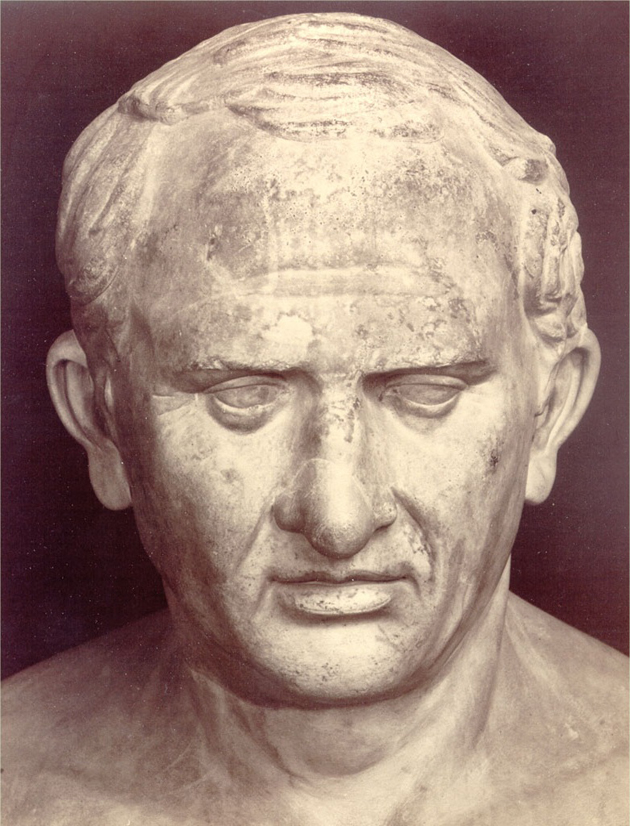

One of the great early philosophers, Marcus Tullius Cicero (106 BC - 43 BC), also the leading lawyer, orator, and Roman senator of his day (during the rule of Julius Caesar), also advanced that position. He wrote volumes on what is the true nature of law and government. In his book On the Republic, Cicero wrote: "True law is right reason in agreement with nature; it is of universal application, unchanging and everlasting."

When Cicero wrote that true law is "right reason," he assigned it an objective, universal quality. To Cicero, reason is the most divine of all human characteristics as it is reason that separates man from all other creatures that God created and is therefore the one quality that man and God have in common. As he wrote: "That animal which we call man... full of reason and prudence, has been given a certain distinguished status by the Supreme God who created him; for he is the only one among so many different kinds and varieties of living beings who has a share in reason and thought, while all the rest are deprived of it." Because law comes from right reason, and reason is divine as one human aspect that connects us to God while separating us from the rest of the creatures on the planet, it stands to reason that the law that comes from reason contains a divine element as well.

Roman Philosopher Cicero - Possibly the first political scientist: Above.

In the second part of his quote, Cicero claimed that law is also "in agreement with nature." What Cicero meant by this is that law is in agreement with our nature as human beings.

The significance of this understanding - that Law has divine and natural elements to it - is that it makes law universal, infallible and unchangeable. If laws were human and made by humans, then they would be imperfect just as humans are. They could change, mold and evolve with time just as people and societies do. They could also be different and diverse just as humans are. But just as God, by definition, is the epitome of universality and infallibility, any law that comes from God must be perfect as well. It must be single and universal and transcend all time and all cultures. Cicero clearly recognized this when he wrote, "there will not be different laws at Rome and at Athens, or different laws now and in the future, but one eternal and unchangeable law will be valid for all nations and all times, and there will be one master and ruler, that is, God, over us all..."

What this all boils down to is summed up nicely in a statement by Cicero: "God's law is 'right reason.' When perfectly understood it is called 'wisdom.' When applied by government in regulating human relations it is called 'justice." Justice, he explained, "originates in our natural inclination, as being created by God in His image, to love our fellow men."

Cicero was assassinated by order of Marc Antony some forty years before the birth of Christ. It is interesting that Cicero taught the same message that Jesus himself would teach in his short time on Earth.

Religion Was Central to the Success of the American Experiment --

Religious principles and biblical precepts were central to the success of the American experiment. The belief in God and his creation was at the very core of their belief in Natural law and the natural ordering of society and liberty. It was their belief that allowed them to gravitate towards the government philosophy of John Locke, on which our nation's values were based. Religious principles form the basis of the ideals stated in the Declaration of Independence, the ordered liberty embodied in our Constitution, and the conviction we have as a nation to recognize the inherent dignity in all human life and to send our brave men and women all over the globe to fight for the rights of others. Religious principles were, and still are, essential to the security of the freedom we claim to stand for and to the foundation that grounds our nation's founding ideals. In short, the great American Experiment was founded on religion and needs that support if posterity is to enjoy what is promised in the Declaration of Independence.

The key to America's religious liberty success story is its focus on the sovereignty of the individual and its constitutional order. The Founders argued that virtue derived from religion is indispensable to limited government. The Constitution therefore guaranteed religious free exercise while prohibiting the establishment of a national religion. This Constitutional order produced a constructive relationship between religion and state that balances citizens' dual allegiances to God and earthly authorities without forcing believers to abandon (or moderate) their primary loyalty to God. This reconciling of civil and religious authorities, and the creation of a Constitutional order that gave freedom to competing religious groups, helped develop a popular spirit of self-government. All the while, religious congregations, family, and other private associations exercise moral authority that is essential to maintaining limited government. The American Founders frequently stated that virtue and religion are essential to maintaining a free society because they preserve "the moral conditions of freedom."

James Madison said that men should conduct themselves as if they "have a duty towards the Creator." (See his 1786 Memorial and Remonstrance). "This duty is precedent, both in order of time and in degree of obligation, to the claims of Civil Society," he wrote.

Thomas Paine and Benjamin Franklin, two of our most important Founding Fathers, did not necessarily see eye-to-eye on religion. Franklin was raised in a devout Puritan home and Paine was a Deist. As a deist, Paine believed that God created the world but then allowed it to operate according to natural laws. Deists believe God does not intervene in the lives of his human creations. Rather, morality should come from reflecting on benevolence of God in creating such a perfect and finely-ordered world. Franklin, on the other hand, believed strongly in an active, ever-present God.

Although Franklin was raised in a devote Puritan home, he did not fully embrace the Calvanism of his upbringing. As an adult, he put his faith in an active God who watched over his natural creation and could, on occasion, intervene in the lives of his human creation as well.

Franklin and Paine often sparred over God's role in the world and in people's lives. At one point Mr. Franklin wrote to Mr. Paine to implore him to put his deist sentiments aside and emphasize the importance of religion in his writings:

... You yourself may find it easy to live a virtuous life, without the assistance afforded by religion; you having a clear perception of the advantages of virtue, and the disadvantages of vice, and possessing a strength of resolution sufficient to enable you to resist common temptations. But think how great a portion of mankind consists of weak and ignorant men and women, and of inexperienced, inconsiderate youth of both sexes, who have need of the motives of religion to restrain them from vice, to support their virtue, and retain them in the practice of it till it becomes habitual, which is the great point for its security. And perhaps you are indebted to her originally, that is, to your religious education, for the habits of virtue upon which you now justly value yourself. You might easily display your excellent talents of reasoning upon a less hazardous subject, and thereby obtain a rank with our most distinguished authors. For among us it is not necessary, as among the Hottentots, that a youth, to be raised into the company of men, should prove his manhood by beating his mother.

If men are so wicked with religion (as Paine often complained), what would they be if without it. I intend this letter itself as a proof of my friendship, and therefore add no professions to it; but subscribe simply yours. - Ben Franklin

In other words, he argues that because God is active in the affairs of man, there is pressure for men to keep virtuous. Religion, he explains, is a check on the pernicious tendencies of man.

Benjamin Franklin indeed believed in an active God who presided over the destinies of his creations and was involved in the affairs of men. He would write: "Without the Belief of a Providence that takes Cognizance of, guards and guides, and may favour particular Persons, there is no Motive to Worship a Deity, to fear its Displeasure, or to pray for its Protection." That is why he believed that faith and prayer were essential in order that Providence continue His blessings on our nation. He also believed that God answered prayer. In July 1787, during the meeting of the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia when tempers were flaring among the delegates, Franklin called for prayer to bring reconciliation to the political differences of the body. As James Madison noted in his Journal from the of the Constitutional Convention, the distinguished 86-year-old delegate from Philadelphia delivered the following words:

Mr. President

The small progress we have made after four or five weeks close attendance and continual reasonings with each other, our different sentiments on almost every question, several of the last producing as many 'nays' and 'ays,' is methinks a melancholy proof of the imperfection of the Human Understanding. We indeed seem to feel our own want of political wisdom, some we have been running about in search of it. We have gone back to ancient history for models of Government, and examined the different forms of those Republics which having been formed with the seeds of their own dissolution now no longer exist. And we have viewed Modern States all round Europe, but find none of their Constitutions suitable to our circumstances.

In this situation of this Assembly, groping as it were in the dark to find political truth, and scarce able to distinguish it when presented to us, how has it happened, Sir, that we have not hitherto once thought of humbly applying to the Father of lights to illuminate our understandings? In the beginning of the Contest with Great Britain, when we were sensible of danger we had daily prayer in this room for the divine protection. Our prayers, Sir, were heard, and they were graciously answered. All of us who were engaged in the struggle must have observed frequent instances of a Superintending providence in our favor. To that kind providence we owe this happy opportunity of consulting in peace on the means of establishing our future national felicity. And have we now forgotten that powerful friend? I have lived, Sir, a long time, and the longer I live, the more convincing proofs I see of this truth- that God governs in the affairs of men. And if a sparrow cannot fall to the ground without his notice, is it probable that an empire can rise without his aid? We have been assured, Sir, in the sacred writings, that 'except the Lord build the House they labour in vain that build it.' I firmly believe this; and I also believe that without his concurring aid we shall succeed in this political building no better than the Builders of Babel: We shall be divided by our little partial local interests; our projects will be confounded, and we ourselves shall become a reproach and bye word down to future ages. And what is worse, mankind may hereafter from this unfortunate instance, despair of establishing Governments be Human Wisdom and leave it to chance, war and conquest.

I therefore beg leave to move, that henceforth prayers imploring the assistance of Heaven, and its blessings on our deliberations, be held in this Assembly every morning before we proceed to business, and that one or more of the Clergy of the City be requested to officiate in that service.

Roger Sherman, delegate from Connecticut, seconded the motion.

While many refer to the 55 delegates to the Constitutional Convention and those men, like Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, who drafted the Declaration of Independence as our "Founding Fathers," the term (or group) actually includes many others, such as those whose actions and writings led to the American Revolution. However, for this discussion, it is worth noting that this core group of 55 delegates to the Constitutional Convention represents the general religious sentiments of those who shaped the political foundations of our nation. As confirmed by public record, the delegates to the Convention included 28 Episcopalians, 8 Presbyterians, 7 Congregationalists, 2 Lutherans, 2 Dutch Reformed, 2 Methodists, 2 Roman Catholics, 1 unknown, and 3 deists (those who believe that God created the world but then allowed it to operate according to natural laws. Deists believed God did not intervene in the lives of his human creation). Overall, 93% of the delegates were members of Christian churches. And all - that is, a full 100% - were deeply influenced by a biblical view of mankind and government.

Where did our biblical view of mankind and government come from? It stemmed from the Christian roots of our thirteen original colonies. Beginning in the seventeenth century, settlers from Spain, France, Sweden, Holland, and Great Britain claimed land in the New World and formed colonies along its eastern coast. Spain controlled the West Indies. The French owned land from Quebec all the way down to the end of the Mississippi River in New Orleans. And the British colonized most of the Atlantic coast from Massachusetts down to Georgia.

The first permanent settlement was the English colony at Jamestown, which was established in 1607 in what is now Virginia. Similar to the other colonial charters granted by Britain, the First Charter of Virginia emphasized the Christian character of the colony's purpose. The Charter read: "We, greatly commending and graciously accepting of, their desires for the furtherance of so noble a work, which may, by the providence of Almighty God, hereafter tend to the glory of His Divine Majesty in the propagating of the Christian religion to such people as yet live in darkness and miserable ignorance of the true knowledge and worship of God."

In 1620, the Pilgrims followed and set up a colony at Plymouth, in what is now Massachusetts. Many of the Pilgrim women and children didn't survive the first winter. Yet they refused to return to England and they refused an opportunity to live in the Netherlands. They wanted the opportunity to establish a political commonwealth governed by biblical standards where they could raise their children and live according to the teachings of Christ. The Mayflower Compact, their initial governing document, clearly stated that what they had undertaken was for "the glory of God and the advancement of the Christian faith." William Bradford, the second governor of Plymouth, said: "The colonists cherished a great hope and inward zeal of laying good foundations for the propagation and advancement of the Gospel of the kingdom of Christ in the remote parts of the world." Plymouth became the first fully self-governing colony.

In June 1630 the Puritan colony of Massachusetts Bay was established. In that year, Governor John Winthrop landed in Massachusetts with 700 people in 11 ships to serve God and establish a pure church - pure in worship and in doctrine. (The Pilgrims and Puritans wanted to establish a new land where they could live the teachings of the gospel). Massachusetts Bay would begin the Great Migration, which lasted sixteen years and brought more than 20,000 Puritans to New England. While still on his ship, the Arbella, Winthrop wrote the sermon he would deliver to the new colonists as they were ready to set out and establish their first settlement. The sermon was titled "A Model of Christian Charity." In that sermon, he sought to articulate the reasons for the new colony. He talked about avoiding a shipwreck. "Now the only way to avoid this shipwreck and to provide for our posterity is to follow the Counsel of Micah, to do Justly, to love mercy, to walk humbly with our God." The "shipwreck" that he referred to was the wrath of God that falls on peoples or nations who fail to do God's will. To avoid the shipwreck, they would have to establish a truly godly society. Winthrop talked about the need to love one another and serve one another - to be merciful, kind, compassionate, sharing, and selfless. This part of the sermon was clearly reminiscent of the Sermon on the Mount.

Go Back

The term "self-governing" refers to the ability of individuals to exercise control over oneself. It is the internal obligation one feels to do the right thing. It is the willingness of individuals to consciously choose and hold onto productive principles that apply in diverse situations. Self-government means self-reliance, self-discipline, and self-improvement. As Thomas Paine said, self-governing individuals are necessary to have a self-governing society. Representative democracy ultimately depends on the moral character of the people and of the representatives elected. As James Madison, chief architect of the Constitution, wrote: "To suppose that any form of government will secure liberty or happiness without any virtue in the people, is a chimerical idea."

Self-governing individuals are necessary in order that the United States can hope to maintain a government of constitutional limits and of a size and scope that can be accountable to the people.

The debate at the core of the growing socialist nature of our government is how much should government do to help those who are less fortunate than others? An entire political party and an entire social movement has been created to answer that question: Total redistribution and equality of status. They are devoted to redefining what the United States stands for, the nature of government, and the new rights that individuals are entitled to and those that government can now regulate in the name of social justice. They are devoted to the tearing down of the fundamental institutions on which successful self-government is based, such as the family, church, and an education system that educates and not indoctrinates. They are devoted a tireless agenda of trying to "do good without God."

But good government depends on the character and virtue of the people it represents.

Character is built by overcoming obstacles. People can and do raise themselves out of poverty. The success stories of millions of immigrants paint a picture of the long-run rewards of discipline, perseverance, and sacrifice. If those stories are to continue, we must protect our liberties, accept our responsibilities, and practice virtue. We must never lose sight of the primary functions of government, as laid out in our Declaration of Independence; otherwise, we have a government in charge of defining its functions rather than We the People defining our government. If we wish to hold on to the grand notion, established for this nation by our Founders, that sovereign power to govern rests first and foremost with the People, then we honor our founding principles. According to the Declaration, protecting persons and protecting property are the two main functions of good government. When government steps beyond those legitimate functions, it steps outside the bounds of justice. As James Madison wrote: "That is not a just government, nor is property secure under it, where the property which a man has in his personal safety and personal liberty, is violated by arbitrary seizures of one class of citizens for the service of the rest."

But the more fundamental debate that is going on in this country is the one which speaks directly to the character of each individual. And that debate is ultimately the one over religion and its proper role in our society.

Character is defined by the set of moral qualities that a person possesses or one's moral strength. Character is the inner strength to do what is right even when no one is looking.

There is a deeply-embedded understanding in this country, stemming from our very founding settlers, patriots, and Founding Fathers, that religion and morality are fundamentally linked. Morality has roots in religious doctrine. In the Old Testament, God handed down a series of commandments to guide man's conduct. Man is free indeed, but even the Bible teaches that he should not be free to do everything he pleases. And so we have the Ten Commandments (on which common law, including criminal law, has been based). In the New Testament, God has established a new covenant with all who believe. And so we see a strong them of forgiveness, compassion, selflessness, and love in those books. Jesus himself summed up his Father's commandments in two great commandments: the command to love God with all one's heart and mind (see Deuteronomy 6:5), and the command to love the neighbor as the self (see Leviticus 19:18). Morality sees its roots therefore in the desire to always do good and do what is right. Religion provides the motivation and the reason to do good. It provides meaning to live a moral life. Thomas Paine believed that the moral duty of man consists in imitating the moral and beneficence of God.

There are moral limits to human behavior that are intertwined into our very nature. They not simply accidents or norms born out of history. There are permanent standards of what is right and wrong, and what is natural and what is unnatural. We regard such limits as something that must be conserved to protect character from avarice, envy, unhealthy ambition, entitlement, a sense of superior self-worth, and destruction. As Russell Kirk noted in his book, The Conservative Mind, we have a "belief in a transcendent order, or body of natural law, which rules society as well as conscience."

Our Founding Fathers saw morality as dependent on religious principles rather than on some internal value system because they believed that morality is based on timeless truths. Despite the various religious beliefs of our Founders, they shared a strong common belief that moral truths exist and are necessary for people to responsibly self-govern their own affairs. And that's why we see the historical record full of advice from them to remain a moral and religious people.

Lasting virtue is never forced; it is not passed in our genes. It is born out of a respect for certain fundamental and eternal truths based on right versus wrong, good versus bad, fair versus unfair. It is born out of love and deep respect for one's fellow man and for the rights that he values for everyone.

And so we see that the debate has intensified over whether religion is critical to self-government. I would argue that there is no element more important to one's individual behavior than the influence of religion and the power of the conscience. And that's why I believe that our Founders intended for the government to encourage the full expression of religious rights and not try to prevent it (using its arbitrary "Wall of Separation" to chill that expression).

Unfortunately, all too often we hear that government and schools aren't supposed to legislate or teach morality. But if we look at the roots of government and the purpose of law, we find out that the exact opposite is true.

One of the great early philosophers, Marcus Tullius Cicero (106 BC - 43 BC), also the leading lawyer, orator, and Roman senator of his day (during the rule of Julius Caesar), also advanced that position. He wrote volumes on what is the true nature of law and government. In his book On the Republic, Cicero wrote: "True law is right reason in agreement with nature; it is of universal application, unchanging and everlasting."

When Cicero wrote that true law is "right reason," he assigned it an objective, universal quality. To Cicero, reason is the most divine of all human characteristics as it is reason that separates man from all other creatures that God created and is therefore the one quality that man and God have in common. As he wrote: "That animal which we call man... full of reason and prudence, has been given a certain distinguished status by the Supreme God who created him; for he is the only one among so many different kinds and varieties of living beings who has a share in reason and thought, while all the rest are deprived of it." Because law comes from right reason, and reason is divine as one human aspect that connects us to God while separating us from the rest of the creatures on the planet, it stands to reason that the law that comes from reason contains a divine element as well.

In the second part of his quote, Cicero claimed that law is also "in agreement with nature." What Cicero meant by this is that law is in agreement with our nature as human beings.

The significance of this understanding - that Law has divine and natural elements to it - is that it makes law universal, infallible and unchangeable. If laws were human and made by humans, then they would be imperfect just as humans are. They could change, mold and evolve with time just as people and societies do. They could also be different and diverse just as humans are. But just as God, by definition, is the epitome of universality and infallibility, any law that comes from God must be perfect as well. It must be single and universal and transcend all time and all cultures. Cicero clearly recognized this when he wrote, "there will not be different laws at Rome and at Athens, or different laws now and in the future, but one eternal and unchangeable law will be valid for all nations and all times, and there will be one master and ruler, that is, God, over us all..."

What this all boils down to is summed up nicely in a statement by Cicero: "God's law is 'right reason.' When perfectly understood it is called 'wisdom.' When applied by government in regulating human relations it is called 'justice." Justice, he explained, "originates in our natural inclination, as being created by God in His image, to love our fellow men."

Cicero was assassinated by order of Marc Antony some forty years before the birth of Christ. It is interesting that Cicero taught the same message that Jesus himself would teach in his short time on Earth.

Religion Was Central to the Success of the American Experiment --

Religious principles and biblical precepts were central to the success of the American experiment. The belief in God and his creation was at the very core of their belief in Natural law and the natural ordering of society and liberty. It was their belief that allowed them to gravitate towards the government philosophy of John Locke, on which our nation's values were based. Religious principles form the basis of the ideals stated in the Declaration of Independence, the ordered liberty embodied in our Constitution, and the conviction we have as a nation to recognize the inherent dignity in all human life and to send our brave men and women all over the globe to fight for the rights of others. Religious principles were, and still are, essential to the security of the freedom we claim to stand for and to the foundation that grounds our nation's founding ideals. In short, the great American Experiment was founded on religion and needs that support if posterity is to enjoy what is promised in the Declaration of Independence.

The key to America's religious liberty success story is its focus on the sovereignty of the individual and its constitutional order. The Founders argued that virtue derived from religion is indispensable to limited government. The Constitution therefore guaranteed religious free exercise while prohibiting the establishment of a national religion. This Constitutional order produced a constructive relationship between religion and state that balances citizens' dual allegiances to God and earthly authorities without forcing believers to abandon (or moderate) their primary loyalty to God. This reconciling of civil and religious authorities, and the creation of a Constitutional order that gave freedom to competing religious groups, helped develop a popular spirit of self-government. All the while, religious congregations, family, and other private associations exercise moral authority that is essential to maintaining limited government. The American Founders frequently stated that virtue and religion are essential to maintaining a free society because they preserve "the moral conditions of freedom."

James Madison said that men should conduct themselves as if they "have a duty towards the Creator." (See his 1786 Memorial and Remonstrance). "This duty is precedent, both in order of time and in degree of obligation, to the claims of Civil Society," he wrote.

Thomas Paine and Benjamin Franklin, two of our most important Founding Fathers, did not necessarily see eye-to-eye on religion. Franklin was raised in a devout Puritan home and Paine was a Deist. As a deist, Paine believed that God created the world but then allowed it to operate according to natural laws. Deists believe God does not intervene in the lives of his human creations. Rather, morality should come from reflecting on benevolence of God in creating such a perfect and finely-ordered world. Franklin, on the other hand, believed strongly in an active, ever-present God.

Although Franklin was raised in a devote Puritan home, he did not fully embrace the Calvanism of his upbringing. As an adult, he put his faith in an active God who watched over his natural creation and could, on occasion, intervene in the lives of his human creation as well.

Franklin and Paine often sparred over God's role in the world and in people's lives. At one point Mr. Franklin wrote to Mr. Paine to implore him to put his deist sentiments aside and emphasize the importance of religion in his writings:

... You yourself may find it easy to live a virtuous life, without the assistance afforded by religion; you having a clear perception of the advantages of virtue, and the disadvantages of vice, and possessing a strength of resolution sufficient to enable you to resist common temptations. But think how great a portion of mankind consists of weak and ignorant men and women, and of inexperienced, inconsiderate youth of both sexes, who have need of the motives of religion to restrain them from vice, to support their virtue, and retain them in the practice of it till it becomes habitual, which is the great point for its security. And perhaps you are indebted to her originally, that is, to your religious education, for the habits of virtue upon which you now justly value yourself. You might easily display your excellent talents of reasoning upon a less hazardous subject, and thereby obtain a rank with our most distinguished authors. For among us it is not necessary, as among the Hottentots, that a youth, to be raised into the company of men, should prove his manhood by beating his mother.

If men are so wicked with religion (as Paine often complained), what would they be if without it. I intend this letter itself as a proof of my friendship, and therefore add no professions to it; but subscribe simply yours. - Ben Franklin

In other words, he argues that because God is active in the affairs of man, there is pressure for men to keep virtuous. Religion, he explains, is a check on the pernicious tendencies of man.

Benjamin Franklin indeed believed in an active God who presided over the destinies of his creations and was involved in the affairs of men. He would write: "Without the Belief of a Providence that takes Cognizance of, guards and guides, and may favour particular Persons, there is no Motive to Worship a Deity, to fear its Displeasure, or to pray for its Protection." That is why he believed that faith and prayer were essential in order that Providence continue His blessings on our nation. He also believed that God answered prayer. In July 1787, during the meeting of the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia when tempers were flaring among the delegates, Franklin called for prayer to bring reconciliation to the political differences of the body. As James Madison noted in his Journal from the of the Constitutional Convention, the distinguished 86-year-old delegate from Philadelphia delivered the following words:

Mr. President

The small progress we have made after four or five weeks close attendance and continual reasonings with each other, our different sentiments on almost every question, several of the last producing as many 'nays' and 'ays,' is methinks a melancholy proof of the imperfection of the Human Understanding. We indeed seem to feel our own want of political wisdom, some we have been running about in search of it. We have gone back to ancient history for models of Government, and examined the different forms of those Republics which having been formed with the seeds of their own dissolution now no longer exist. And we have viewed Modern States all round Europe, but find none of their Constitutions suitable to our circumstances.

In this situation of this Assembly, groping as it were in the dark to find political truth, and scarce able to distinguish it when presented to us, how has it happened, Sir, that we have not hitherto once thought of humbly applying to the Father of lights to illuminate our understandings? In the beginning of the Contest with Great Britain, when we were sensible of danger we had daily prayer in this room for the divine protection. Our prayers, Sir, were heard, and they were graciously answered. All of us who were engaged in the struggle must have observed frequent instances of a Superintending providence in our favor. To that kind providence we owe this happy opportunity of consulting in peace on the means of establishing our future national felicity. And have we now forgotten that powerful friend? I have lived, Sir, a long time, and the longer I live, the more convincing proofs I see of this truth- that God governs in the affairs of men. And if a sparrow cannot fall to the ground without his notice, is it probable that an empire can rise without his aid? We have been assured, Sir, in the sacred writings, that 'except the Lord build the House they labour in vain that build it.' I firmly believe this; and I also believe that without his concurring aid we shall succeed in this political building no better than the Builders of Babel: We shall be divided by our little partial local interests; our projects will be confounded, and we ourselves shall become a reproach and bye word down to future ages. And what is worse, mankind may hereafter from this unfortunate instance, despair of establishing Governments be Human Wisdom and leave it to chance, war and conquest.

I therefore beg leave to move, that henceforth prayers imploring the assistance of Heaven, and its blessings on our deliberations, be held in this Assembly every morning before we proceed to business, and that one or more of the Clergy of the City be requested to officiate in that service.

Roger Sherman, delegate from Connecticut, seconded the motion.

While many refer to the 55 delegates to the Constitutional Convention and those men, like Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, who drafted the Declaration of Independence as our "Founding Fathers," the term (or group) actually includes many others, such as those whose actions and writings led to the American Revolution. However, for this discussion, it is worth noting that this core group of 55 delegates to the Constitutional Convention represents the general religious sentiments of those who shaped the political foundations of our nation. As confirmed by public record, the delegates to the Convention included 28 Episcopalians, 8 Presbyterians, 7 Congregationalists, 2 Lutherans, 2 Dutch Reformed, 2 Methodists, 2 Roman Catholics, 1 unknown, and 3 deists (those who believe that God created the world but then allowed it to operate according to natural laws. Deists believed God did not intervene in the lives of his human creation). Overall, 93% of the delegates were members of Christian churches. And all - that is, a full 100% - were deeply influenced by a biblical view of mankind and government.

Where did our biblical view of mankind and government come from? It stemmed from the Christian roots of our thirteen original colonies. Beginning in the seventeenth century, settlers from Spain, France, Sweden, Holland, and Great Britain claimed land in the New World and formed colonies along its eastern coast. Spain controlled the West Indies. The French owned land from Quebec all the way down to the end of the Mississippi River in New Orleans. And the British colonized most of the Atlantic coast from Massachusetts down to Georgia.

The first permanent settlement was the English colony at Jamestown, which was established in 1607 in what is now Virginia. Similar to the other colonial charters granted by Britain, the First Charter of Virginia emphasized the Christian character of the colony's purpose. The Charter read: "We, greatly commending and graciously accepting of, their desires for the furtherance of so noble a work, which may, by the providence of Almighty God, hereafter tend to the glory of His Divine Majesty in the propagating of the Christian religion to such people as yet live in darkness and miserable ignorance of the true knowledge and worship of God."

In 1620, the Pilgrims followed and set up a colony at Plymouth, in what is now Massachusetts. Many of the Pilgrim women and children didn't survive the first winter. Yet they refused to return to England and they refused an opportunity to live in the Netherlands. They wanted the opportunity to establish a political commonwealth governed by biblical standards where they could raise their children and live according to the teachings of Christ. The Mayflower Compact, their initial governing document, clearly stated that what they had undertaken was for "the glory of God and the advancement of the Christian faith." William Bradford, the second governor of Plymouth, said: "The colonists cherished a great hope and inward zeal of laying good foundations for the propagation and advancement of the Gospel of the kingdom of Christ in the remote parts of the world." Plymouth became the first fully self-governing colony.

In June 1630 the Puritan colony of Massachusetts Bay was established. In that year, Governor John Winthrop landed in Massachusetts with 700 people in 11 ships to serve God and establish a pure church - pure in worship and in doctrine. (The Pilgrims and Puritans wanted to establish a new land where they could live the teachings of the gospel). Massachusetts Bay would begin the Great Migration, which lasted sixteen years and brought more than 20,000 Puritans to New England. While still on his ship, the Arbella, Winthrop wrote the sermon he would deliver to the new colonists as they were ready to set out and establish their first settlement. The sermon was titled "A Model of Christian Charity." In that sermon, he sought to articulate the reasons for the new colony. He talked about avoiding a shipwreck. "Now the only way to avoid this shipwreck and to provide for our posterity is to follow the Counsel of Micah, to do Justly, to love mercy, to walk humbly with our God." The "shipwreck" that he referred to was the wrath of God that falls on peoples or nations who fail to do God's will. To avoid the shipwreck, they would have to establish a truly godly society. Winthrop talked about the need to love one another and serve one another - to be merciful, kind, compassionate, sharing, and selfless. This part of the sermon was clearly reminiscent of the Sermon on the Mount.